A record 512bn of work hours were lost around the world in 2023 because of the risk of heat exposure, says a new report from the Lancet Countdown on Health and Climate Change.

Agricultural workers in low-income countries were disproportionately affected, the authors say, costing countries around 8% of their GDP in 2023.

The findings are part of the ninth iteration of the annual report, which features indicators of climate change and human health, such as heat mortality, air pollution exposure and how countries are adapting.

The report highlights the many health inequalities in how energy is used around the world. According to the report, the number of deaths caused by fossil fuel-derived air pollution decreased by 7% over 2016-21 – mainly due to wealthy nations phasing out coal.

However, the vast majority of low-income countries still rely heavily on biomass and other “dirty” fuels in their homes. Dr Marina Romanello, lead author and executive director of the Lancel Countdown, added that women and children are usually in charge of sourcing and burning the fuel, making them particularly vulnerable.

The authors also call out governments and fossil fuel companies for “fuelling the fire” through continuing investment into oil and gas assets that are likely to push the world past key warming targets. The study notes that fossil fuel subsidies exceeded national health spending in 2022 for more than 20 countries around the world.

Romanello told journalists her “concern” that governments and companies “keep on promoting fossil fuel expansion, to the detriment of health and survival of people worldwide”.

Extreme heat

The impacts of extreme heat are “insidious”, Prof Ollie Jay, director of the Heat and Health Research Centre at the University of Sydney and author on the report, told a press briefing.

He explained that certain groups of people are more vulnerable to heat – including infants, the elderly, pregnant women and people with pre-existing medical conditions.

In 2023, infants and adults older than 65 faced a new record high of 14 days of heatwaves per person, the report finds. This value exceeds the previous record, set in 2022, by more than 20%.

The combination of a warming and ageing world is putting more people at risk, the report says. For example, in 2023, demographic changes alone would have driven a 65% increase in heat-related deaths among over-65s, compared to the 1990-99 average. The addition of global warming pushes this percentage up to 167% – the highest highest level recorded.

Across the whole population, the authors find that people were exposed to an average of 50 more “health-threatening heat days” in 2023 than they would have been in a world without climate change. (These are defined as days when the daily average temperature exceeds the 84.5th percentile of the 1986-2005 daily regional average.)

Beyond this global average figure, less-developed countries are much more likely to see such health-threatening days. For example, 31 such countries experienced at least 100 more days of health-threatening heat due to climate change.

The map below shows the average number of days with health-threatening temperatures attributable to climate change per year, over 2019-23, by country. Darker colours mean more health-threatening days.

Heat stress is particularly dangerous for outdoors workers, who are often directly exposed to the heat while undertaking manual labour. In 2023, around one-quarter of the world’s population worked outdoors.

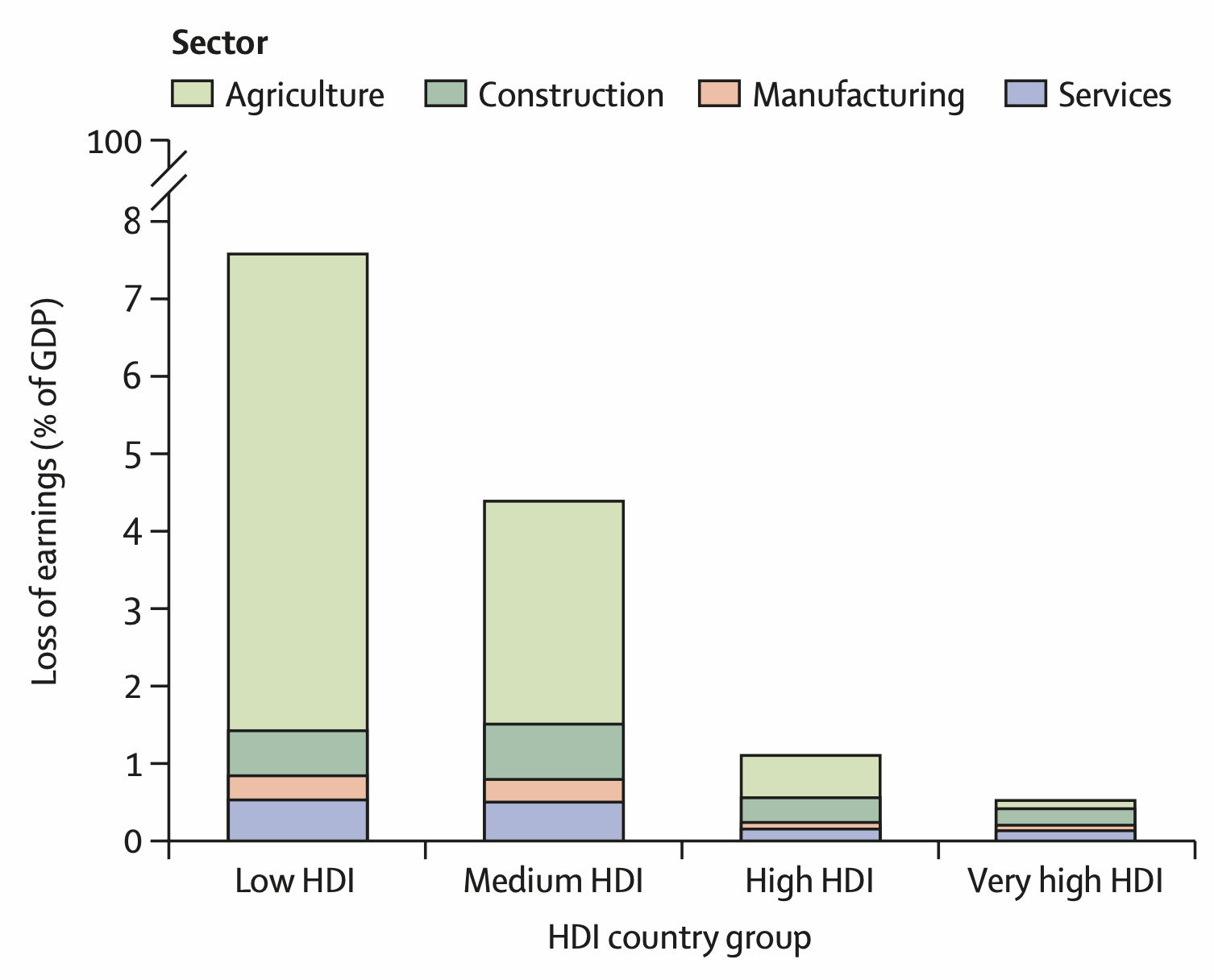

The report finds that countries with the lowest human development index (HDI) – a measure of a country’s development – have the highest proportion of outdoors workers, largely due to their reliance on the agricultural sector.

The report measures the number of “potential work hours lost” due to heat exposure, by considering temperature, humidity and “typical metabolic rate of workers in specific economic sectors”.

It finds that heat exposure drove a record high of 512bn potential work hours lost in 2023 – around 1.5 times the 1990-99 average. Approximately two-thirds of this loss was in the agricultural sector, mainly in low and medium HDI countries. In total, the global potential loss of income due to extreme heat reached a record high of $835bn in 2023, the report says.

Wealthy countries were generally the least impacted by heat stress. Very high HDI countries only saw around 41 lost hours per worker due to heat, causing an economic loss of around 1% of their GDP. Meanwhile, low HDI countries lost more than 200 hours per worker, and saw almost an 8% loss in their GDP.

The graph below shows percentage GDP loss due to heat stress in low, medium, high and very high HDI countries, in agriculture (light green), construction (dark green), manufacturing (orange) and services (purple).

This year’s report also introduces a new indicator assessing how night-time heat affects sleep loss. The authors estimate that high night-time temperatures led to 5% more sleep hours lost in 2019-23 than in 1986-2005.

The authors say that air conditioning is an “effective technology for reducing heat exposure”. However, they say that it can also be an example of “maladaptation”, as it is “expensive and energy-intensive, overwhelms energy grids on hot days, and can contribute to greenhouse gas emissions”.

They note that emissions from air conditioning increased by 8% over 2016-21. However, access to the technology is not universal. In 2021, 48% of households in very high HDI countries had air conditioning compared to only 5% of those in low HDI countries.

Malnutrition and disease

The report also unpacks how climate change is exacerbating food insecurity and malnutrition.

It finds that the total proportion of global land area affected by extreme drought for at least one month per year increased from 15% in 1951-60 to 44% in 2013-24.

The authors warn that “the higher frequency of heatwave days and drought months in 2022, compared with 1981-2010, was associated with 151 million more people experiencing moderate or severe food insecurity across 124 countries”.

This year, the authors also introduced a new indicator tracking changes in rainfall events. The authors divide up the world into 80km grid squares and monitor the number of rainfall events that exceed the 99th percentile of 1961-90 rainfall.

Over the last decade, extreme rainfall events increased in more than 61% of grid squares, the report finds. The authors warn that high rainfall can drive an increase in flooding, which can lead to a range of negative health incomes including outbreaks of certain diseases.

For example, Vibrio bacteria in coastal waters can cause “severe” gastrointestinal infections and “life-threatening sepsis”. The study finds that the length of coastlines with suitable conditions for the bacteria reached a new record high of more than 88,000km in 2023 – 32% above the 1990-99 average.

In addition, the total population living within 100km of coastal waters with conditions suitable for Vibrio transmission has reached a record high of 1.42 billion.

The authors also find that the climatic conditions for mosquitoes to transmit dengue, malaria and West Nile virus have increased between 1951-60 and 2014-23 as the world has warmed.

Fossil fuels

On energy use, the study notes that, “given the high greenhouse gas and air pollution emission intensity of coal, its phase-out is crucial to protect people’s health”.

Over 2016-21, very high HDI countries have seen a reduction in the share of energy that comes from coal. (The UK became the first G7 country to phase out coal power in September 2024.)

However, the report highlights that all low HDI countries are still very dependent on coal. Over 2016-21, the share of electricity that comes from coal in low HDI countries increased from less than 1% to 10%.

According to the report, the number of deaths caused by fossil fuel-derived air pollution – specifically, tiny particulate matter known as PM2.5 – decreased by 156,000 over 2016-21 – a drop of 7%. This is mainly due to reduced pollution from coal burning in high and very high HDI countries.

Dr Marina Romanello, the lead author of the report and executive director of the Lancet Countdown, told the press briefing that this an important result as it shows the “enormous potential of coal phase-out to improve health”.

However, the report also warns that biomass burning caused 1.24 million deaths in 2021 – an increase of 135,000 from 2016 levels.

For example, the report finds that 2.3bn people still cook using biomass. In low HDI countries, around 92% of countries use solid biomass for their household energy needs. Conversely, in very high HDI countries, this number is around 10%.

Romanello explained that biomass is “very unreliable, very unstable and particularly polluting”. She added:

“When households rely on biomass, it is often women and children that are in charge of sourcing the fuel, so it also generates disproportionate impacts on these groups.”

The authors also call out fossil fuel companies for “fuelling the fire”. One of the report’s indicators assesses the compatibility of fossil fuel company strategies with the Paris Agreement. It says:

“As of March 2024, the strategies of the 114 largest oil and gas companies have put them on track to exceed their share of greenhouse gas emissions consistent with limiting global heating to 1.5C by 189% in 2040, up from the 173% excess projected in March, 2023.”

The report analyses 86 countries that are collectively responsible for 93% of global CO2 emissions. They find that, in 2022, these countries awarded a record $1.2tn in fossil fuel subsidies. This funding exceeded 10% of national health spending in 47 countries and 100% in 23 countries.

Romanello shared her “concern” with the press briefing that “governments and companies keep fuelling the fire, keep on promoting fossil fuel expansion, to the detriment of health and survival of people worldwide”.

Adaptation

Finally, the report assesses countries’ preparedness for the health impacts of climate change. This section presents a mixed picture.

The report finds that, as of February 2024, fewer than half of the most recent country climate pledges made under the Paris Agreement mentioned a “health keyword”.

However, the report also finds areas of progress. For example, at the end of 2022, only four countries had put forward health national adaptation plans (HNAPs) outlining how they will plan for and adapt to the impacts of climate change on health. Just one year later, this number had jumped up to 40 countries.

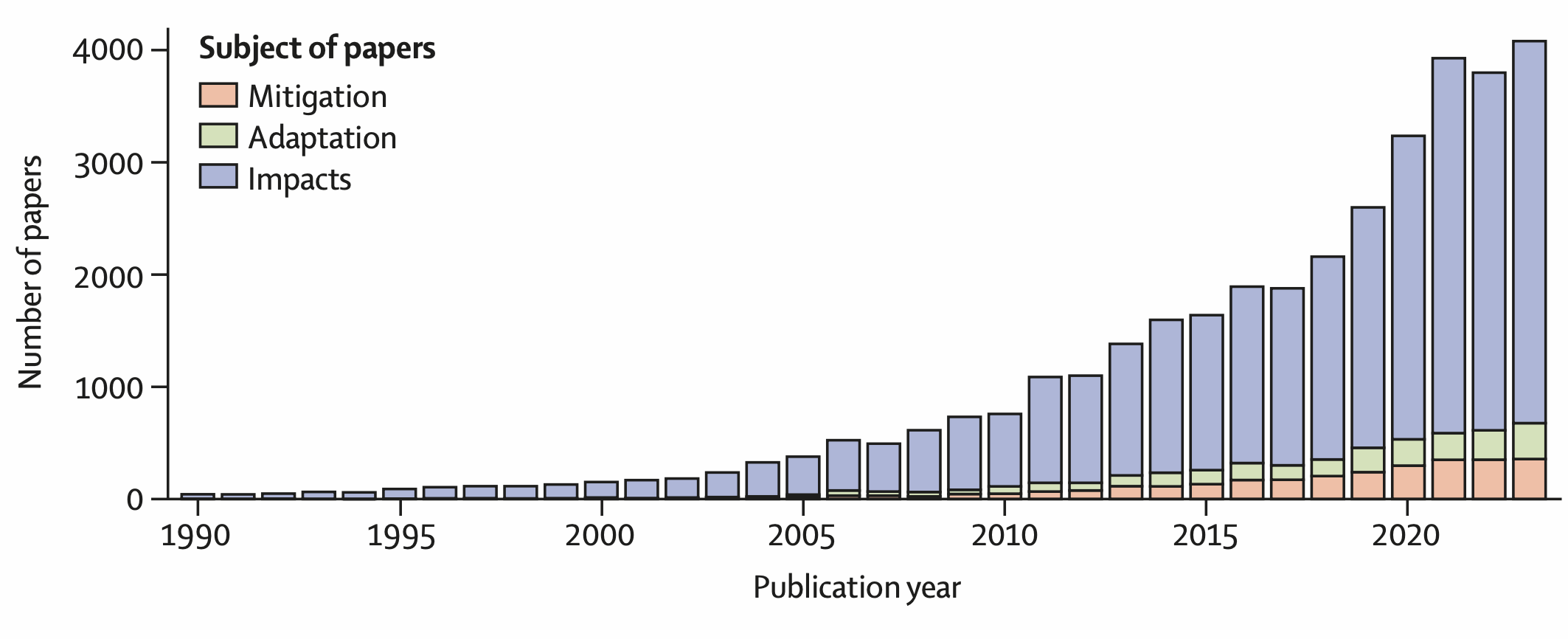

Furthermore, the authors find that scientific engagement into the links between climate change and health is increasing. The number of scientific papers investigating the link between climate change and health reached a record high in 2023, with the vast majority of papers focusing on impacts, rather than mitigation or adaptation.

The graph below shows the number of academic papers published each year over 1990-2023 on climate change and health, focused on mitigation (orange), adaptation (green) and impacts (purple).

The report finds that some countries are already implementing successful adaptation measures. For example, it explains that countries with health early warning systems saw a 73% decrease in the number of people killed per extreme weather event between 2000-09 and 2014-23. In countries without such early warning systems, the decrease was only 21%.

The authors note that “the reduction cannot be directly attributed to the implementation of health early warning systems”, but suggest that countries that implement these systems likely have higher “engagement with climate change adaptation efforts”.

The positive news in this report is “not enough to tip the balance” or to “secure a healthy future”, Romanello told the press briefing. However, she said it is “meaningful progress” which can be “built on”.

Dr Jeremy Farrar served as chief scientist of the World Health Organisation, and was previously the director of the Wellcome Trust – the main funding body behind this report. He told journalists at the press briefing that despite the “incredible evidence base” available, the health community “have been too slow to make the case that climate change is a health crisis”.

However, he praised the intersectoral collaboration between health and climate experts, and said he hopes we are “turning a corner” on making sure that climate change is seen as a “health issue”.

M, Romanello. et. al. (2024), The 2024 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: facing record-breaking threats from delayed action, The Lancet

Sharelines from this story