The number of new coal plants under development in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) region has reached record lows since the signing of the Paris Agreement in 2015.

The OECD is an intergovernmental organisation with 38 member countries, founded in 1961 to stimulate economic growth and global trade. It includes many of the world’s wealthiest countries.

In all, the number of proposed coal plants in the OECD region has decreased from 142 in 2015 to five today – a 96% fall.

This is according to the latest data from Global Energy Monitor’s Global Coal Plant Tracker (GCPT), which includes the third quarter (Q3) of 2024.

The GCPT catalogues all coal-fired power units 30 megawatts (MW) or larger, with the first survey dating back to 2014.

The fall in proposals puts the OECD region well on its way to meeting UN secretary-general Antonio Guterres’s 2019 call for “no new coal”, defined as the cancelling of all unabated coal proposals not already under construction.

It means that one of the five remaining proposals could be the last new coal-fired power station to ever be built in the OECD.

The OECD and no new coal

Of the 13 OECD countries with coal plant proposals in 2015, all but Turkey have since pledged to stop building new coal plants.

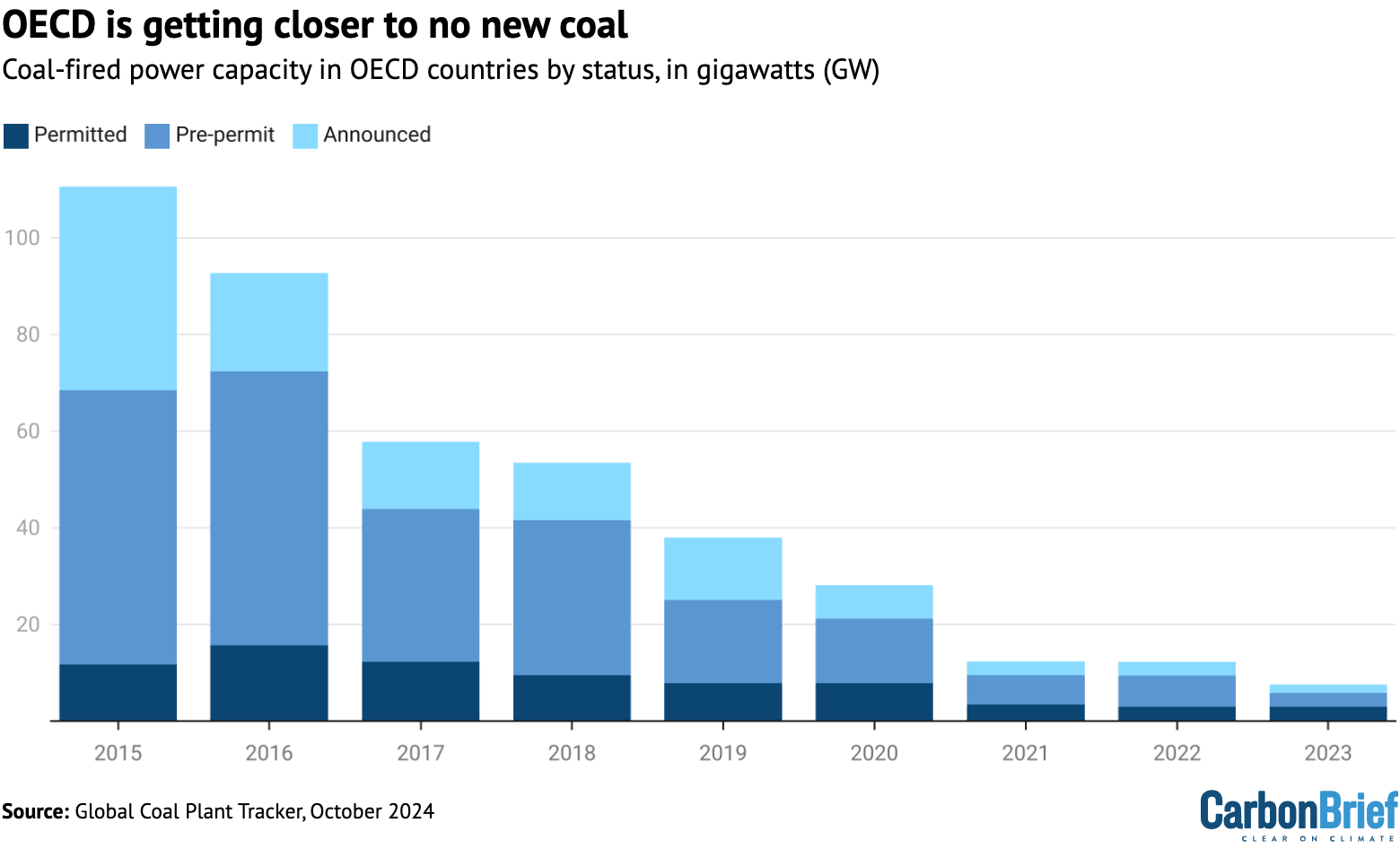

Indeed, since 2015, proposed coal-fired capacity in the OECD has fallen from 142 coal proposals totalling 111 gigawatts (GW) to just five proposals totalling 3GW, GCPT data shows.

However, there are exceptions for coal plants that significantly lessen or “abate” carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions through the use of carbon capture and storage (CCS) technology.

Four of the five proposals – shown in the map below – include plans for CCS.

Moreover, none of the five proposals currently have the necessary permits for construction. This means it will likely be several years before construction begins – if they are built at all, as most of the proposals in the OECD since 2015 have been abandoned entirely.

Of the 111GW of new coal capacity that was proposed in 2015, 82% (91GW) has since been shelved or cancelled, compared to 17% (19GW) commissioned.

This is a large part of the reduction in the coal pipeline in the OECD, shown in the figure below.

The most recent coal plants to enter the construction phase in the OECD broke ground in 2019. Its 1GW of capacity remains under construction today.

The 111GW of proposals in 2015 listed in the GCPT were located across 13 countries: Australia, Canada, Colombia, Germany, Greece, Israel, Italy, Japan, Poland, South Korea, Turkey, the UK and the US.

Since 2015, 12 of the 13 countries have pledged support for no new coal, whether as part of the international Powering Past Coal Alliance or through a domestic moratorium on new coal plant permits. The UK phased out coal power entirely this year.

These commitments to no new coal have been aided by the decreasing costs of competing power sources, including gas and – increasingly – solar and wind power.

Additionally, many countries have seen sustained opposition campaigns to new coal plants over the pollution they would cause, their high energy costs and population displacement.

As the OECD turns away from new coal, coal power capacity in the region peaked in 2010 at 655GW and has since declined by about one-third to 443GW, as countries shut down ageing coal plants.

Turkey resists no new coal

To date, the government of Turkey has resisted calls for no new coal, despite repeated rollbacks in its coal plans.

The vast majority of the country’s proposed coal plants have never materialised, as shown in the figure below.

Specifically, since 2015, more than 70GW of planned coal plant capacity in Turkey has been called off, compared to 6GW commissioned, translating into a cancellation rate of 92% since 2015. This is one of the highest cancellation rates in the world, GCPT data shows.

Coal plant proposals in Turkey face a myriad of challenges, including strong public opposition over coal plant pollution and coal industry privatisation. Additionally, domestic lignite coal is low-quality and unreliable, often leading many plants to use higher-cost imported coal instead, weakening the economic case for continued reliance on coal.

In the third quarter of 2024, the licenses for two coal plants – Karaburun and Kirazlıdere – were cancelled due to irregularities in the environmental permitting process and the loss of interest in the investment by plant sponsors. Another plant, Malkara, was shelved due to a lack of activity, GCPT notes.

The developments have left Turkey with only one coal plant proposal – a remarkable development after being among the top 10 countries with proposed coal-powered capacity for nearly a decade.

Despite this, Turkey has not committed to ending new coal plant proposals. Indeed, its recently updated enhanced climate plan, known as a nationally determined contribution submitted during COP29, makes no mention of coal phaseout.

The country’s remaining proposal is a 688MW two-unit expansion of the sizable Afşin-Elbistan power station complex in the city of Kahramanmaraş.

Local residents have opposed the project, saying the increase in pollution in the densely populated city will lead to thousands of premature deaths and cost billions of dollars.

Australia, Japan, the US and ‘clean coal’

The remaining four coal plant proposals in the OECD are located in Australia, Japan and the US.

While the government of Australia recently pledged support for no new coal and the Japanese and US governments were part of the recent G7 commitment to coal phaseout, the three countries also support CCS to lessen or “abate” emissions from coal plants.

Abated coal plants may be considered compatible with no new coal pledges if they “substantially reduce” carbon emissions enough to meet Paris-aligned targets.

Critics argue that coal CCS proposals are more expensive and polluting than cleaner electricity alternatives, often relying heavily on government subsidies in order to be economically viable.

Only a handful of CCS coal plants have ever reached commercial operation – and none have captured as much of the resulting CO2 as they were targeting.

The Japanese government signed on to a G7 agreement earlier this year to phase out unabated coal power by the mid-2030s and continues to promote a suite of “clean coal” technologies, both domestically and abroad.

The country’s single remaining coal plant proposal is a new coal “gasification” unit at J-Power’s Matsushima power station, dubbed GENESIS. The plant would gasify the coal, then co-fire the resulting gases with biomass, ammonia and hydrogen, before using CCS to abate the resulting emissions.

Under outgoing president Joe Biden, the US also signed on to the G7 agreement and was one of twelve countries that joined the Powering Past Coal Alliance during COP28 in 2023.

The country has two Department of Energy (DOE)-backed coal-fired power plant proposals that include plans for CCS, as required under pending Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) regulations for new coal power plants.

While the future of both the coal pledges and regulations are uncertain, given the recent re-election of Donald Trump, to date the former president has been unable to turn the tide for coal. More coal power capacity was retired under Trump’s first term than either Barack Obama or Biden, and no new coal plants have been built in the US for over a decade.

Australia’s Labor party voted into power in 2022 recently joined a COP29 call for no new unabated coal. The country has not commissioned a new coal plant since 2012, with over 13GW of proposed coal-fired capacity cancelled since 2010.

The country’s remaining coal proposal, the Collinsville (Shine Energy) power station, has been touted by its sponsors as a “high efficiency, low emissions” (HELE) coal project with plans to include CCS.

Despite these sparse plans for the development of further coal projects, therefore, it seems clear that the end is in sight for coal power in the OECD.

Sharelines from this story