In 1985, French secret service agents were sent to plant two bombs on our flagship, the Rainbow Warrior, ahead of its journey leading a peaceful anti-nuclear protest.

The evening of 10 July saw a lively atmosphere aboard the Rainbow Warrior as the crew and guests celebrated Steve Sawyer’s birthday. Margaret Mills, another crew member, had baked a birthday cake decorated with a jelly bean rainbow. People mingled and enjoyed drinks and slices of cake.

Little did they know that one of the guests was a French spy, observing all that was taking place to feed back to his colleagues. The spy departed just after 8pm, and at about 8.15pm, the skippers of all the protest yachts going to Moruroa descended into the hold of the Rainbow Warrior for a planning meeting.

Outside, French combat divers were attaching two bombs to the ship’s hull below the water line. The divers had motored across the harbour in an inflatable zodiac dinghy from a secluded launching ramp at Stanley Point, Devonport.

After planting the bombs, the pair escaped by swimming west towards the Auckland Harbour Bridge to be picked up. The pilot of the zodiac motored towards Mechanics Bay to be picked up by a campervan.

Close to midnight, with their guests gone, the Rainbow Warrior’s skipper Peter Willcox and some of the crew went off to bed. The remainder sat around the mess room table, chatting and enjoying the last bottles of beer.

The French agents in a zodiac dinghy motored across from Stanley Point (red) to Marsden Wharf (purple) where the Rainbow Warrior lay. The two divers escaped by swimming towards Auckland Harbour Bridge while the zodiac pilot motored towards Mechanics Bay (blue) to be picked up by a campervan.

The bombers’ strike

Suddenly, a big thud rocked the ship. The lights went out. There was the sharp crack of breaking glass. Then a sudden roar of water. The crew’s first thought was that they had been hit by a tugboat.

Martini Gotje went down below to check that Hanne Sorensen was not in her cabin. Fernando Pereira went down to his cabin to retrieve his camera equipment.

Then, there was a second explosion.

Peter Willcox called for everyone to abandon ship. Within minutes the ship was sunk.

Later, Willcox recalled: “I stood there looking at the boat with all of these bubbles coming out. That’s when Davey said ‘Fernando is down there’. I remember arguing with him, saying no, Fernando has gone to town, that’s what he always did. ‘No’ he said. ‘Fernando is down there’.”

Greenpeace photographer Fernando Pereira drowned. He had recently celebrated his 35th birthday. His young children would soon have their lives shattered by the news.

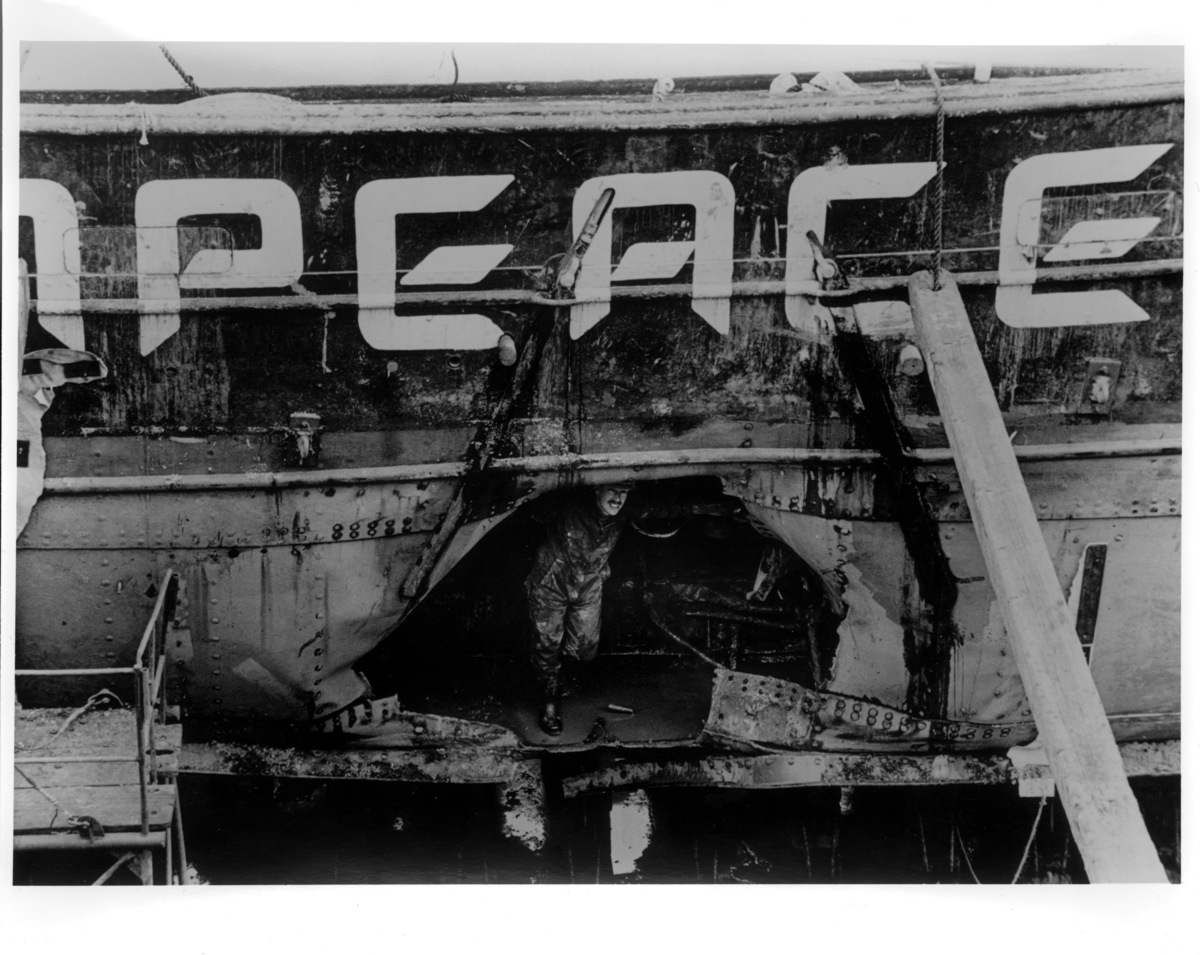

The first bomb made a massive hole two metres by three metres wide into the engine room. The second bomb severely damaged the propeller shaft. There may have been more deaths if everyone had been in bed, as metal from the first explosion had penetrated many of the empty cabins. The stunned Rainbow Warrior crew spent the rest of the night in or on the steps of the Wharf Police Station across the road from Marsden Wharf. Their plans for the Rainbow Warrior to lead the anti-nuclear protest flotilla to Moruroa Atoll were over.

Background to the bombing

At the time of the bombing, the Rainbow Warrior was about to lead a group of anti-nuclear testing vessels into the Pacific. To appreciate why the ship was bombed by the French government, it’s important to understand the political environment of the time, and how Greenpeace’s campaign against testing in the Pacific was so significant.

The Rainbow Warrior was about to lead a flotilla of anti-nuclear testing vessels to Moruroa Atoll in French Polynesia. To appreciate why the Rainbow Warrior was bombed, it is important to first understand how nuclear testing in the Pacific became such a controversial issue.

On 6 August 1945, the United States dropped a new and devastating weapon in the form of an atomic bomb on the city of Hiroshima in Japan. Three days later it dropped another atomic bomb on the city of Nagasaki. The USA dropped these nuclear weapons to speed up the end of the war against Japan and avoid a costly ground invasion of the Japanese home islands.

But the world had never seen such powerful weapons of mass destruction. Each bomb was more powerful than 10,000 tons of TNT explosive. Entire sections of the cities were totally destroyed and tens of thousands of men, women and children were killed outright or in the days and weeks afterwards. These bombs released radioactive fallout which contaminated the environment. Many people would die later from exposure to radiation. Women gave birth to deformed babies. To this day, historians argue about whether or not such weapons should ever have been used against Japan.

After World War II, tension developed between the USA and the USSR. What became known as the Cold War (1945-1991) began, where the two superpowers and their allies competed to spread their different forms of government across the world.

The USA and the USSR competed to produce the most powerful nuclear weapons in order to ensure their security. Governments now knew that if they launched nuclear weapons at another nuclear power, they would most likely be destroyed by their opponent’s weapons.

The two sides very nearly started a nuclear war over the Cuban Missile Crisis. Given the fragile post-World War II climate, the nuclear powers became careful not to provoke each other.

The USA, Britain and France sought remote areas to develop their nuclear weapons. Up until the 1960s, atmospheric nuclear tests were carried out in the Pacific by these powers.

The USA used the Marshall Islands. The British used Christmas Island and the Australian outback. France moved its testing programme from Algeria to French Polynesia in 1966. Nuclear devices were suspended by balloons high above the ground and detonated so that scientists could take measurements.

Atmospheric testing meant that radioactive fallout was carried by the wind for vast distances, which contaminated the environment. Significant numbers of people living on nearby islands like Rongelap in the Marshall Islands have since developed cancer. Women have had miscarriages and some have given birth to deformed babies (known as “jellyfish babies”).

From the late 1950s people in many countries became very concerned about the effects of nuclear testing on people and the environment. Many people in the Pacific argued that if the tests were safe, why did the nuclear powers not test in their own countries.

The USA and Britain stopped testing in the South Pacific in the early 1960s. Protest movements started up and the governments of Vanuatu, New Zealand, Australia and others called on France to stop testing at Moruroa Atoll. The French Government refused to stop tests and downplayed the risks.

In June 1972, Greenpeace yacht Vega sailed into the forbidden zone outside Moruroa Atoll to stop the upcoming nuclear test by its presence. This was an extremely dangerous protest action, as the crew could be be exposed to nuclear fallout from the explosion. David McTaggart (the skipper), Nigel Graham and Grant Davidson made blocks to seal the vents, to stop radioactive fallout entering the cabin. It was agreed that if they survived the nuclear blast and shockwave one crew member would expose himself on the deck to start the engine and motor out of the danger zone. After being ordered to leave, McTaggart refused to follow a French naval vessel out of the zone. This resulted in a chase where the Vega was rammed and McTaggart and crew were put in detention. Although the test went ahead, the Greenpeace action raised global awareness about the issue and put pressure on France to stop testing.

The New Zealand and Australian governments took France to the International Court of Justice in 1973 to try to stop the tests. However, France refused to follow the court’s ruling that it should stop testing. Norman Kirk, the New Zealand Prime Minister, sent two New Zealand navy frigates to protest on the edge of the Moruroa testing area.

A flotilla of civilian yachts were also protesting, including the Greenpeace yacht Vega skippered again by David McTaggart. Frustrated by McTaggart’s persistent non-violent protest actions, the French military boarded the Vega, where they severely beat McTaggart and one of his crew. He was hospitalised and lost vision in one of his eyes for several months. The French government tried to say his injuries were from a fall, but a crew member from the Vega smuggled out photos of the beating. This caused outrage in the international media and the French government was left humiliated.

Greenpeace was seen as a group of troublemakers by some members of the French government and military. The French navy found it very difficult to deal with non-violent protesters who would not cooperate. The protests led to the French abandoning atmospheric tests in favour of underground tests during 1974. However, protests at Moruroa continued in the hope that underground tests would also be stopped.

In 1985, Greenpeace sent its ship Rainbow Warrior on a Pacific Peace Voyage. The ship would help to evacuate the people of Rongelap Atoll in the Marshall Islands. In 1954, the US tested a nuclear weapon on Bikini Atoll which was one thousand times more powerful than the bomb dropped on Hiroshima. The people of Rongelap, 150 kilometres away, were not warned about the test and suffered from the radioactive contamination for decades afterwards. Eventually they asked Greenpeace to help move them to a new, uncontaminated atoll. Once the Rongelapese had been relocated, the ship would sail to Vanuatu and on to New Zealand. From Auckland, the Rainbow Warrior would lead a flotilla of vessels to Moruroa Atoll, in French Polynesia, to protest against the upcoming French nuclear tests.

Why did the French bomb the Rainbow Warrior?

The French government saw its nuclear testing programme as essential for France’s security (even though a nuclear armed world is hardly a secure one). But negative publicity about the testing would put pressure on the French government to stop its programme. It was for this reason that the French government wanted to stop the Rainbow Warrior’s upcoming anti-nuclear protest.

The Rainbow Warrior was a large vessel which could act as a flagship for the smaller protest yachts. French naval vessels would not be able to intimidate it as easily as the other, more fragile yachts. The Rainbow Warrior could carry large amounts of supplies, which meant that it could protest for a long period of time. The communications equipment on board would allow the crew to maintain radio contact with the outside world and send up-to-the-minute reports and photos to international news organisations.

The French navy would find it extremely difficult to deal with the non-violent tactics of the protest vessels. To avoid this, the French secret service DGSE was ordered to launch “Operation Satanique,” where French secret service agents were sent to New Zealand to sink the Rainbow Warrior before it could lead the protest flotilla.

The Aftermath

On 11 July 1985, news spread of dramatic explosions on the Auckland waterfront. Greenpeace flagship the Rainbow Warrior had been sunk while moored at Marsden Wharf. One crew member, Fernando Pereira, had been killed. Navy divers who retrieved his body at 4am discovered that the blast came from outside the hull of the ship and a murder enquiry was launched by New Zealand police.

Police investigation

The police had a lucky break. On the evening of 10 July, two members of the Auckland Outboard Boating Club were watching out for people stealing boating equipment. At around 9.30pm, they saw a man in a wetsuit dragging a zodiac ashore after going under the Ngatipi Bridge on Tamaki Drive. The man was picked up by a couple in a Newmans Toyota campervan. One of the men took down the van’s registration number and gave it to the police.

After the bombing, the police were able to follow this lead, and when the couple went to return the van to the Newmans depot in Mt Wellington two days later, the staff delayed them long enough for the police to arrive. The couple were travelling on fake Swiss passports and would eventually be unmasked as French agents Alain Mafart and Dominique Prieur.

French involvement

The French government initially denied any involvement in the bombing. Alain Mafart and Dominique Prieur continued to pretend that they were a Swiss couple on honeymoon. Over the following weeks, their story unravelled as their passports were shown to be forgeries. The police gradually uncovered evidence that would show a highly organised operation involving more than ten French agents. For two months the French government continued to deny any involvement.

Under pressure, the French government launched an inquiry to find out if French agents were responsible for the attack. This Tricot Inquiry would state that the agents in New Zealand were only spying on Greenpeace and did not sink the ship. The scandal intensified as the French media published further allegations about French involvement. The French Defence Minister, Charles Hernu, was forced to resign and the head of the French secret service (the DGSE), Pierre Lacoste, was sacked. On 22 September 1985, the French Prime Minister, Laurent Fabius, gave a televised address in which he revealed that French agents bombed the Rainbow Warrior and that they acted on orders.

The New Zealand public was outraged that France could carry out such an attack on New Zealand territory. Thousands of New Zealand men had died fighting to defend France during World War I and II and many were angry this was how a former ally was treated. Many New Zealanders were already angry about how France was continuing to test nuclear weapons at Moruroa Atoll. These tests were seen as a threat to the environment and the people of the South Pacific. People argued that if (as the French claimed) the tests were safe, they should be carried out in France.

Greenpeace gained huge sympathy over the bombing, and donations poured in. The fact that New Zealand’s traditional allies, the United Kingdom and the United States, did not condemn France’s actions caused further bitterness. Following this, the New Zealand government pursued a more independent stance in world affairs. In 1987, New Zealand passed the Nuclear Free Zone, Disarmament, and Arms Control Act. The bombing cemented nuclear free policies as part of New Zealand’s identity.

The two French agents were found guilty of manslaughter. The New Zealand judge sentenced them each to ten years’ imprisonment on 22 November 1985. The French government wanted its agents returned to France.

In January 1986, New Zealand farm produce exports began to face obstacles in the French markets. The New Zealand government feared that if its exports to the European Community were blocked, the New Zealand economy would be severely damaged. This situation led the two governments to come to an agreement with the help of the United Nations. The agreement, reached on July 1986, led to a French apology, compensation fee and an agreement not to interfere with New Zealand exports to Europe. In return, the agents would serve three years on Hao Atoll in French Polynesia. Many New Zealanders did not like this deal and the nation was outraged when France broke the agreement and brought the two agents back to France within two years.

The sinking of the Rainbow Warrior failed to stop the protests at Moruroa Atoll. Greenpeace gained a huge amount of sympathy in New Zealand and around the world following the bombing, and if anything it had the opposite effect to what the French wanted. Fernando Pereira’s death made many protesters more determined to go and protest at Moruroa. Donations and offers of help continued to flood in. Greenpeace International was able to send its other large ship, The Greenpeace, to lead the protest at Moruroa Atoll.

The Rainbow Warrior’s Peter Wilcox and Grace O’Sullivan boarded the Greenpeace yacht Vega and sailed to Moruroa to protest. They were arrested and deported. Bunny McDiarmid joined The Greenpeace and Lloyd Anderson joined the crew of the yacht Varangian.

The international attention gained from the bombing raised a much deeper awareness around the issue of nuclear testing amongst governments and people around the world. Indeed, the bombing of the Rainbow Warrior and the resulting international outrage would play a part in the decision by France to end nuclear testing on Moruroa Atoll in 1996.

Arbitration settlement

On 2 October 1987, an international arbitration tribunal sitting in Geneva, Switzerland ordered France to pay Greenpeace US$8.1 million in damages for deliberately sinking the Rainbow Warrior. France agreed to the arbitration after Greenpeace threatened to take France to court in New Zealand. This arbitration settlement was a very significant victory for Greenpeace, as it recognised the organisation’s rights under international law. According to their lawyer, Gary Born, the arbitration showed that “the law was not just something that protected smaller states, it also protected individuals and legal entities like Greenpeace”.

Greenpeace then had the funds to replace the Rainbow Warrior with the ship Rainbow Warrior 2, which would continue the campaign to protect the environment and raise awareness of critical environmental issues around the globe.

The Rainbow Warrior was towed north and scuttled at Matauri Bay. A memorial sculpture overlooks the water. Recreational divers are now able to admire the marine life surrounding the ship, that was used to protect the very creatures that now surround it.

Remembering Fernando

He joined the crew of the Rainbow Warrior to bring his pictures of French nuclear testing to the world. When secret service agents bombed the ship, they killed Fernando Pereira, a man who dedicated his life to peace. A determined photographer, a family man, a Rainbow Warrior – he will always be remembered.

The bombers struck just before midnight on 10 July 1985 as two separate explosions ripped through the hull of the Rainbow Warrior. The second explosion knocked Fernando Pereira unconscious below deck, and as the Warrior swiftly sank, he drowned.

Fernando Pereira, 1950 – 1985

Fernando was born in the town of Chaves in Portugal. As a young man, he fled Portugal to neighbouring Spain to avoid being forced to join the army and fight in the dictator Salazar’s war in Angola. Spain was no safe haven for political refugees at the time, so he travelled for hundreds of kilometres on foot and by hitchhiking until he reached the Netherlands, where he decided to settle. He met and married a Dutch woman, had a family, and pursued his passion for photography.

By 1985, Fernando was a freelance photographer for Greenpeace, and he signed on for the Rainbow Warrior’s six month Pacific voyage. He was a part of the team evacuating the people of Rongelap Atoll, which had been severely contaminated with radioactive fallout following nuclear testing in the region by the USA. His photographs of the evacuation are profoundly moving and showed his professionalism as a photographer.

Evacuation of Rongelap Islanders to Mejato by the Rainbow Warrior crew in the Pacific 1985. (Greenpeace Witness book page 99) The health of many adults and children has suffered as a result of the nuclear fallout from US nuclear tests. The Greenpeace crew took adults, children and 100 tonnes of belongings onboard.

Fernando was a popular crew member who had a great zest for life and a deep conviction for the causes he believed in. If he had not been killed, he would have photographed the protests at Moruroa Atoll.

Three months earlier, he had farewelled his two children in the Netherlands. His daughter Marelle remembers him saying “Just take care of your mom, I’ll do my trip and I’ll be home soon”. She was eight years old. After he left, she went walking in the forest with her brother Paul, who “waved to every plane because that could be the one my dad was in”.

Their innocent young lives would be shattered by the news to come from New Zealand some months later.

“During the summer we went to camp, we were playing a game with a ball with my friends, then one of our teachers came up to me and asked if I could join her because she had something to tell me. My mom was there and I thought that was pretty strange. I did not know what to think of that, so I walked with her to where my mother was sitting with an uncle of mine, but over there I got a strange feeling, I don’t know how to explain that, but I knew something had to be wrong with my dad. It had to be; otherwise my mom would have come over there and talked to me. By the time that I got to my mom she was in tears”.

“The moment that she said he was missing, all the pieces fell together and I cried together with my mom. We packed our bags that afternoon and she took me home. We waited for the news which eventually was of my dad turning up dead”.

Fernando’s Legacy

Marelle and Paul’s lives were changed forever as they grew up without their much loved dad. The French government paid some compensation to his family, but not all of his killers were brought to justice. Twenty years later Marelle gave her view on this.

“What I would like to see happen now… Justice for us, justice for the family if they could tell the truth that would be a beginning, and Mitterrand promising justice at the highest level, if that is justice, letting so many agents escape jail, then that is not justice, not in our eyes and I hope not in the world’s eyes. And, it is never too late for justice”.

The Rainbow Warrior is in Rongelap to assist in the evacuation of islanders to Mejato. Rongelap suffered nuclear fallout in 1954, making it a hazardous place for this community to continue living in. Eyes of Fire: p49

On 10 July 2010, the 25th anniversary of Fernando’s death, a wreath was laid for him. Peter Willcox, the skipper of the Rainbow Warrior on the night of his death, made this tribute to him:

“Fernando did not have to die…We will never forget him. I hope the generations of activists who sail on the new ship will be as determined and as exceptional and as inspired as he was.”

Fernando’s memory remains an inspiration to people who campaign for a green and peaceful future.

In 1995, the Rainbow Warrior II was boarded by French commandos, as it led a further protest against nuclear testing in Moruroa Atoll. When Greenpeace activists were asked for their names, they only gave one: Fernando Pereira.

Declassified NZSIS Report

Supplied to Greenpeace from New Zealand Security Intelligence Service in June 2017, this fifteen page file was declassified in May and provides useful information on the bombing and investigation. From timelines to which French agents involved, this is an invaluable tool for anyone studying the bombing.

Press release from Greenpeace on anniversary of bombing, July 1986

Documentary about the bombing of the Rainbow Warrior

The Boat and the Bomb is a 2005 documentary about the bombing of the Rainbow Warrior.

More resources about the bombing of the Rainbow Warrior

Letters

Press release from Greenpeace on anniversary of bombing, July 1986.

Open letter to the French President from French living in NZ, May 1985.

Letter to the French President from Rainbow Warrior, May 1985.

Telegram message from Helen Clark to Greenpeace, July 1985.

Letter from Tim Shadbolt to Greenpeace, aceepting Rainbow Warrior reception invite, April 1985.

Letter to Walter Lini, Prime Minister of Vanuatu from Greenpeace, 1984.

Letter confirming Federation of Labour’s support of Pacific Peace Campaign, April 1985.

Invoice from Mt Eden Borough Council for reception of Rainbow Warrior event, June 1985.