The US will face a bigger rise in weather-induced supply disruption over the next 15 years than any other country, a new study suggests – although current risks to its consumers are very low.

The modelling study assesses how changes in temperature and rainfall variability and extremes can impact the production of goods and services, and explores how this disruption spreads through supply chains to affect consumers around the world.

The paper, published in Nature Sustainability, finds that all countries will face worsening “weather shocks” to their supply chains by 2040, as climate change alters temperature and rainfall patterns.

In general, middle-income countries face greater risk than high- or low- income countries, the authors find. This is partly because they are located mostly in the subtropics where they are vulnerable to seasonal heat and rainfall extremes, and partly because they tend not to trade with a diverse range of countries.

Nations that rely heavily on domestic production and do not import much from other countries – such as North Korea – are also vulnerable to supply chain risks. This is because they do not have the trade links to resort to when hit by climate-related disruption at home.

Within countries, the poorest members of society face the highest absolute risk, the study says. However they find that the percentage increase in risk will be the greatest for the rich, as they have the highest levels of consumption and low baseline risk.

The authors stress the importance of climate adaptation in reducing risks. The lead author tells Carbon Brief that when countries improve their own resilience by adapting to the changing climate, they also “protect their trade partners”, increasing resilience overall.

“We are all connected through complex linkages, and this is why accelerating adaptation to climate change, not only stopping climate change, is a global public good,” an expert who was not involved in the study tells Carbon Brief.

Modelling trade

As the planet warms, heat extremes are becoming more frequent and rainfall patterns are shifting. In many countries, this is already impacting economic productivity.

For example, drought, floods and heatwaves are already damaging crop yields in countries around the world, causing food prices to spike. Meanwhile, heat stress caused 490bn potential labour hours to be lost globally in 2022, and wiped out the equivalent of 4% of Africa’s GDP.

The new study uses existing research to quantify how temperature and rainfall conditions impact “daily production” in agriculture, manufacturing and services for different countries.

The authors then use climate model projections to assess the impact of climate change on consumers in the past decade (2011-20), present decade (2021-30) and near future (2031-40). They tested three different emission pathways, but found their results to be largely the same for the near-term, so present only one set of results.

They input these projections, along with data on global trade flows, into a simple model of economy called Acclimate, which simulates the interactions between firms and consumers. This allows the authors to calculate how local changes in supply affect the global trade network.

In many cases, the resulting changes in the price or availability of foods and services can reduce consumption, as people are no longer willing or able to buy goods and services.

To assess the impact of climate change on consumption patterns, the authors calculate “consumption risks” – defined as the 90th percentile of consumption reduction, or worst 10% of consumption losses – for a range of different countries and income groups.

The maps below show the percentage reduction in consumption due to rainfall and temperature over 2011-20 by country (left) and the expected percentage increase in consumption risk in 2031-40 (right). Red indicates that consumption dropped, while blue indicates that it increased.

Lennart Quante is a doctoral researcher at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, and lead author of the paper. He tells Carbon Brief that his findings show how “weather shocks will affect production and supply chains around the world”.

The authors find that countries which depend on local production, rather than importing lots of goods and services from elsewhere, are highly vulnerable to local climate shocks. For example, the authors note that North Korea has the highest risk of all low-income countries in this study because its imports from other countries are so low.

Meanwhile, larger countries are typically less vulnerable, because their size allows them to diversify their risk, the authors say. For example, they say the US is resilient to local climate shocks because it is made up of “highly interconnected states”. If a heatwave or period of extreme rainfall hits one part of the US, it is easily able to import goods and services from other areas.

This means that the US is currently facing low consumption losses. However, because this baseline is so low, the paper finds that the US will see the largest percentage increase in consumption risk over the coming decade of any country they studied.

Stephen Hallegatte is a senior climate change adviser at the World Bank and has a decade of experience as a researcher in environmental economics and climate science. Hallegatte, who was not involved in the study, highlights the implications of this finding for smaller countries:

“One intuitive fact that [the authors] quantify is how large countries are less vulnerable, because their size enables risk diversification. This reinforces the idea that small countries, especially small island countries, are extremely vulnerable and need external support to help cope with natural disasters.”

Income inequality

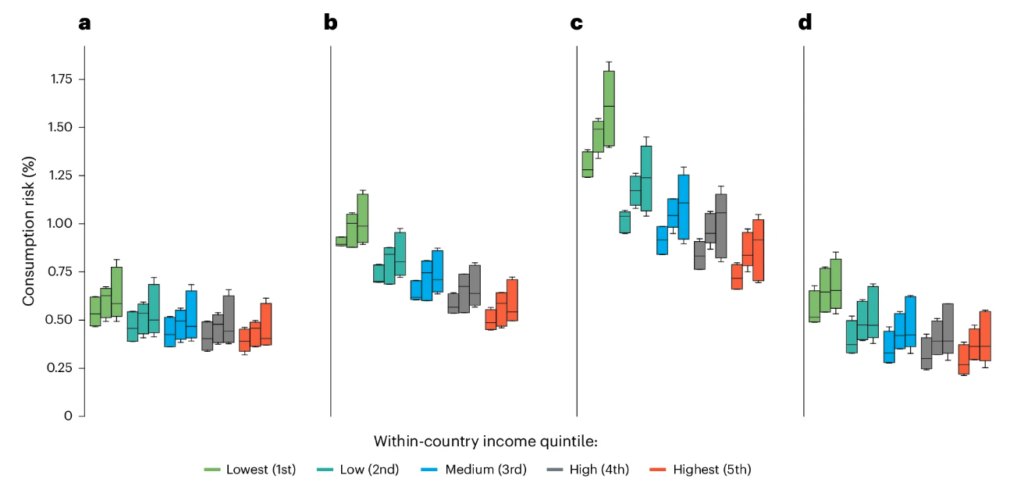

To assess broader trends, the authors used the World Bank’s classification system (pdf) to divide the countries into four income groups. They then divided each country into quintiles (five equal sections) based on their income. The results are shown in the plot below, where higher values indicate greater risk.

From left to right, the four panels show low-income, lower-middle income, upper-middle income and high-income countries. Each colour indicates one fifth of the country’s population, divided by income. Light green, dark green, blue, grey and red indicate income quintiles, from lowest to highest. In each panel, there are three columns of each colour. From left to right, the columns show the consumption risk in the past decade, present decade and near-future decade.

The figure shows that across all income levels, supply chain risk has already increased over the last decade, and is expected to increase further over the next decade.

Consumers in middle-income countries are more vulnerable than those in high- or low-income countries, due to a combination of two main factors, the authors find.

First, middle-income countries are mostly located in the subtropics and are likely to face overlapping climate impacts, including summer extreme heat and seasonal heavy rains, such as monsoons. This combination has the potential to cause considerable damage to local production, they say.

Conversely, higher-income countries, which are mostly located in the mid-latitudes of the northern hemisphere, are less likely to experience these “compounding” impacts because of a more temperate climate.

Second, middle- and high-income countries import most of their goods and services from other countries of the same income level, according to the study. So middle-income countries are vulnerable both to climate impacts at home and those hitting their trade partners.

Conversely, lower-income countries import 65% their consumption from high-income countries, making them less vulnerable to local impacts.

Overall, this means that lower-middle and upper-middle income countries face around twice the supply chain risk of high- or low-income countries.

High-income groups

When focusing on the inequality within countries, the authors find that the lowest-income group in each country currently faces the greatest risks to their consumption.

Hallegate explains that “poor people tend to be more affected because a lot of their consumption is food and agricultural products, and the production of those goods is particularly vulnerable” to climate impacts.

Meanwhile, wealthier households spend a lower proportion of their income on these necessities and are also more likely to be able to afford them even if the price increases. They are also likely to have more savings, buffering them against “short-term shocks”, the paper finds.

However, the study does note that high-income groups will see the biggest jump in risk over the coming decade. This is most pronounced in high-income countries, where the highest-income consumers face an average risk increase of 51% compared with 28% for the lowest-income group.

Nonetheless, this does not mean that high-income groups are more at risk overall, Quante explains:

“The risk increase might be large for the richer countries and richer parts of the populations, but the absolute risk level is still the biggest for the poorest.”

There are limitations to the research, Quante says, noting that it only looks at trade network data and therefore excludes people who live on subsistence farming. This is “very important”, he says, because it means that the study omits the impact of climate change on some of the poorest people in the world.

Hallegatte tells Carbon Brief that this “fascinating” study “builds on the work of a growing community of researchers developing innovative economic models”. However, he also notes that these models “face many challenges and are very much work in progress”, and advises caution in interpreting some of the results. He adds:

“As the paper says, results should not be considered as ‘forecasts’ of what will happen, but as stress tests that highlight the drivers of vulnerability.”

Adaptation and resilience

Supply chains are global, so an impact in one region can result in further impacts elsewhere.

This is also a big opportunity for climate adaptation, Quante tells Carbon Brief, because when people improve their resilience by adapting to the changing climate, they also “protect their trade partners”. He adds that “if everybody does this, there would be a much more resilient trade network” overall.

The study assumes no change in the “underlying base economic structure”, meaning that it does not include the impact of adaptation measures. Quante thinks this is unlikely, telling Carbon Brief that he thinks wealthier countries, at least, are likely to adapt to changes, leading to “indirect global benefits”.

The authors urge countries to “include effective measures to build resilience against weather-induced supply-chain disruptions” in their plans.

Hallegatte tells Carbon Brief that the study highlights the importance of helping countries to adapt to climate change, adding:

“We are all connected through complex linkages, and this is why accelerating adaptation to climate change, not only stopping climate change, is a global public good.”

L, Quante. et. al. (2024), Global economic impact of weather variability on the rich and the poor, Nature Sustainability, doi:10.1038/s41893-024-01430-7

Sharelines from this story