China’s historical emissions within its borders have now caused more global warming than the 27 member states of the EU combined, according to new Carbon Brief analysis.

The findings come amid fraught negotiations at COP29 in Baku, Azerbaijan, where negotiators have been invoking the “principle of historical responsibility” in their discussions over who should pay money towards a new goal for climate finance – and how much.

Carbon Brief’s analysis shows that 94% of the global carbon budget for 1.5C has now been used up, as cumulative emissions since 1850 have reached 2,607bn tonnes of carbon dioxide (GtCO2).

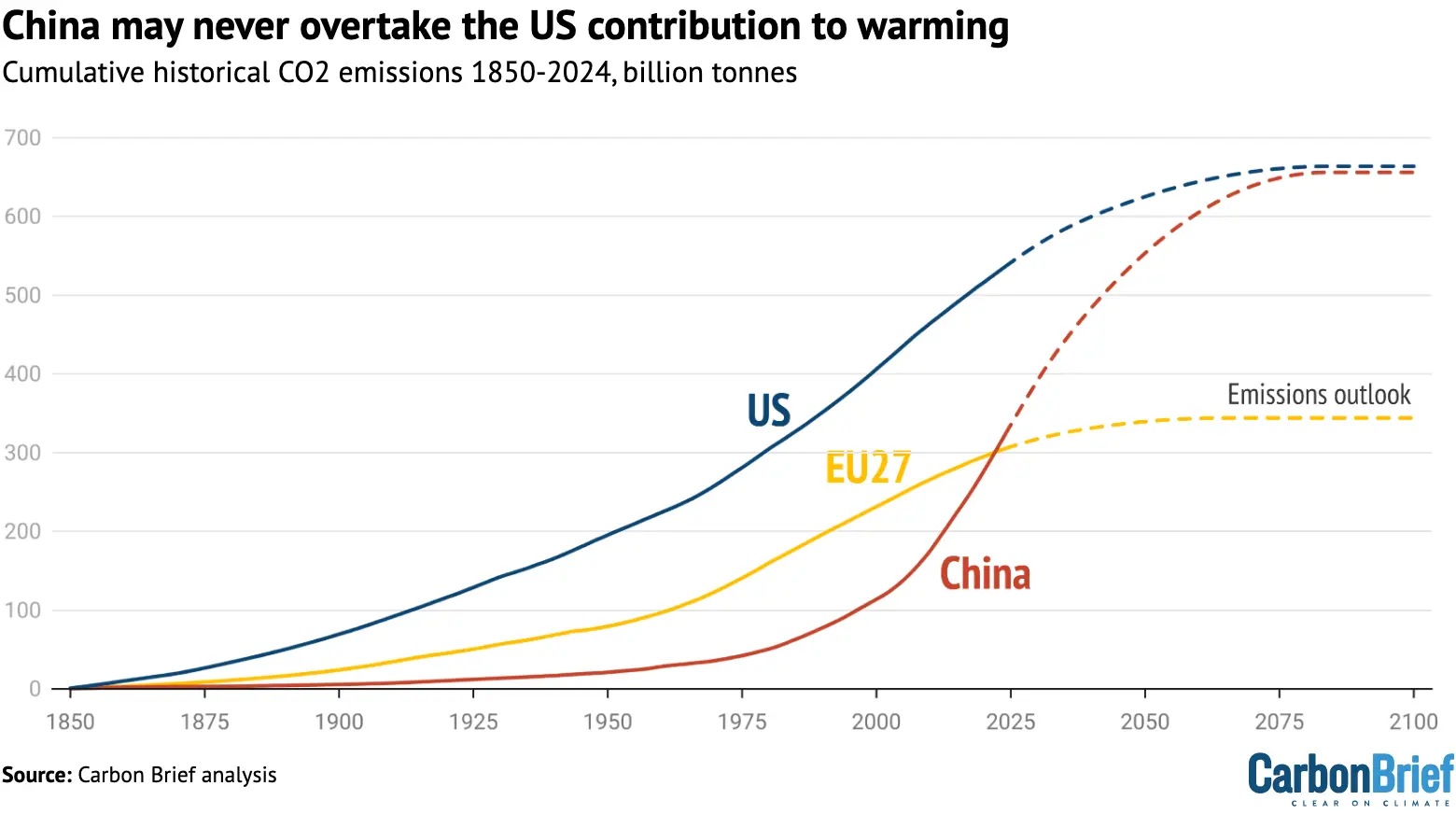

While developed countries have used the majority of this budget, the analysis shows that China’s historical emissions reached 312GtCO2 in 2023, overtaking the EU’s 303GtCO2.

China is still far behind the 532GtCO2 emitted by the US, however, according to the analysis.

Indeed, China is unlikely to ever overtake the US contribution to global warming, based on current policies, committed plans and technology trends in both countries. This is even before accounting for the potential emissions-boosting policies of the incoming Trump presidency.

In addition, China’s 1.4 billion people are each responsible for 227tCO2, a third of the 682tCO2 linked to the EU’s 450 million citizens – and far below the 1,570tCO2 per capita in the US.

The new analysis follows Carbon Brief’s 2021 analysis of historical responsibility, based on emissions taking place within each country’s present-day borders or considering emissions embedded in imports. Further analysis in 2023 assigned responsibility to colonial rulers.

(A table at the end of this article shows which countries have the largest historical emissions according to the full range of metrics, including emissions per person.)

Animated chart shows the cumulative historical emissions of key countries since 1850. Credit: Joe Goodman / Carbon Brief

History matters

Historical CO2 emissions matter for climate change, because there is a finite “carbon budget” that can be released into the atmosphere before a given level of global warming is breached.

For example, in order to limit warming to 1.5C above pre-industrial levels, only around 2,800GtCO2 can be added to the atmosphere, counting all emissions since the pre-industrial period. (This is according to a 2023 study updating figures from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.)

Cumulative emissions since 1850 will reach 2,607CO2 by the end of 2024, according to Carbon Brief’s new analysis, meaning that some 94% of the 1.5C budget will have been used up.

These cumulative historical emissions are directly and proportionally linked to the amount of global warming that has already been seen to date.

Conclusions adopted by countries at the end of the first week at COP29 also make this link, in light of 2024 being on track to be the hottest year on record:

“The [subsidiary body to the UN climate process] SBSTA…expressed utmost concern about the state of the global climate system…with 2024 being on track to be the hottest year on record, which is primarily a result of the long-term warming caused by emissions from pre-industrial times until now.”

In addition, draft text on the new climate finance goal explicitly links responsibility for global warming to finance “burden-sharing arrangements” – meaning who should pay and how much.

In one passage of a draft published on 16 November 2024, there is a reference to the “principle of historical responsibility”. Another passage says that developed-country cumulative emissions should be used as a “proxy for historic responsibility for climate change”. The draft states:

“[D]eveloped country parties shall establish burden-sharing arrangements to enable the delivery of the [new climate finance] goal based on cumulative territorial CO2 emissions…as a proxy for historic responsibility for climate change.”

An alternative option in the draft says that countries should have to contribute to the new climate finance target if they are one of the world’s “top 10 emitters” based on cumulative emissions – and if they have average per-capita incomes above a certain level.

(If agreed, this would mean China, as a top-10 historical emitter, being obliged to contribute to climate finance. However, the draft is not final and is likely to change significantly. Many parts of the draft are enclosed in square brackets, indicating that they are not agreed.)

At the annual UN climate talks, it is also common for developing countries to remind developed nations that they have used up a large share of the world’s carbon budget – and that they should, therefore, be making stronger efforts to cut their emissions.

For example, in the closing plenary of the first week at COP29, Saudi Arabia “lamented depleted carbon budgets…in light of historic cumulative emissions as well as developed countries’ insufficient mitigation efforts”, according to the Earth Negotiations Bulletin.

China’s rising contribution

It is true that developed countries have been the leading contributors to historical emissions. This is despite the fact that China now has the world’s highest emissions on an annual basis.

Put another way, developed countries have made a disproportionately large contribution to current global warming, particularly when considering the number of people that live in them.

This is a key reason why the Paris Agreement says they “should continue taking the lead” on cutting their emissions – and why they must provide climate finance for developing nations.

The 1992 UN climate convention (UNFCCC) listed “developed” countries in Annex I, based on membership of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development at the time.

The convention says that the “largest share of historical and current global emissions of greenhouse gases has originated in developed countries”.

Indeed, at the time of the convention being agreed in 1992, Annex I countries accounted for 22% of the world’s population and a disproportionately large 61% of historical emissions.

By the end of 2024, however, Annex I countries’ share of cumulative historical emissions will have fallen to 52% of the global total. Carbon Brief’s analysis suggests that developing countries – those outside Annex I – will account for a majority of historical emissions in roughly six years.

China’s rapidly rising contribution to cumulative emissions is a major driver of this shift.

In 1992, China’s historical emissions were around two-fifths (41%) the size of the EU’s. By 2015, when the Paris Agreement was finalised, they were still only four-fifths (80%) of the EU’s total.

By the end of 2023, Carbon Brief’s analysis shows that China’s cumulative emissions (red line in the figure below) had overtaken those from the 27 EU member states (yellow).

Still, it is worth emphasising that China’s emissions remain far behind those of the EU on a per-capita basis.

When weighting historical emissions per head of population in 2024, China’s contribution is just 227tCO2 per capita, less than a third of the 682tCO2 for people in the EU27.

(There are several other ways to measure historical contributions. These include adjustments to account for CO2 embedded in imported goods and services, or shifting responsibility under periods of colonial rule. See the table below to compare countries using different metrics.)

US still most responsible

While China is now the world’s second-largest contributor to historical emissions, ahead of the EU27, it remains far behind the US, as shown in the figure below.

With cumulative emissions of 537GtCO2 by the end of 2024, the US total is two-thirds higher than China’s and three-quarters above the EU27.

Still, China is closing the gap, given its annual emissions are now roughly double those of the US. This is clear from the slope of the curves in the chart above, where China’s line is rising steeply.

China may never overtake the US

The fact that China’s annual emissions are so much higher than those from the US begs the question of when might it overtake the US, in terms of its cumulative historical total.

A 2023 article in the Washington Post attempted to answer this question, asserting that China would overtake the US in 2050. However, it used implausible projections in which annual emissions from the US, China and Europe remained almost unchanged for decades.

To attempt a more plausible answer, Carbon Brief has used data from the latest International Energy Agency (IEA) World Energy Outlook, published in October 2024.

Specifically, Carbon Brief looked at how annual emissions in China, the US and EU27 might change under “current policy settings” in the IEA’s “stated policies scenario” (STEPS). This reflects governments’ current and committed plans, as well as the latest energy-price trends.

The dashed lines in the figure below illustrate how the annual emissions of the US, EU and China are each expected to fall steeply under those current policy settings.

Adding these annual emissions outlooks to the historical totals up to this year suggests that China may never overtake the US in terms of its cumulative emissions, as shown in the figure below.

Emissions outlooks are by their nature uncertain. For example, China’s emissions might fail to fall as fast as the IEA expects – or the US might go faster than expected.

On the other hand, the impact of the incoming Trump presidency rolling back climate rules and aiming to “drill baby, drill” would make it even less likely that China would ever overtake the US.

Whether or not China overtakes the US in terms of its historical emissions, it is unlikely to escape pressure to contribute to global flows of climate finance.

At COP29, Ding Xuexiang, Chinese president Xi Jinping’s “special representative” and the nation’s executive vice-premier, notably used the UN language of climate finance to describe Chinese overseas aid for the first time. However, China has insisted that it will only provide such finance voluntarily.

About the data

This analysis is based on historical CO2 emissions from fossil fuel use, cement production, land use, land use change and forestry (LULUCF), during the period 1850-2024.

The approach mirrors the methodology used for Carbon Brief’s analysis of historical responsibility according to emissions within national borders, and when considering colonial rule.

Those articles explain how it is possible to confidently estimate emissions that took place more than 100 years ago, how the analysis deals with changes in national borders, how emissions from land use can be estimated and why the analysis only starts in 1850.

As those articles illustrated, there are many different lenses through which historical responsibility for climate change can be viewed, each offering an alternative viewpoint on the world.

The table below, which is sortable and searchable, shows a selection of the different ways that historical responsibility can be carved up.

It lists countries according to population, historical emissions within their own borders, emissions after accounting for colonial responsibility and the impact of CO2 embedded in trade since 1990.

The table also shows two alternative per capita metrics. The first shows cumulative territorial emissions for each country, divided by its population in 2024. The second shows per-capita territorial emissions in each year, cumulatively added up through to the present day.

(Note that the table excludes countries with a population of less than 1 million people.)

This data is free to use under the terms of Carbon Brief’s CC licence. The licence applies to non-commercial use and requires a credit to “Carbon Brief” and a link to this article.

This article was written by Simon Evans and edited by Leo Hickman. Data analysis was carried out by Verner Viisainen. Visuals by Joe Goodman.

Sharelines from this story