Human-caused climate change made the “unprecedented” wildfires that spread across Brazil’s Pantanal wetlands in June 2024 between four and five times more likely, according to a new rapid attribution study.

South America’s Pantanal – the world’s largest tropical wetland – experienced exceptionally hot, dry and windy conditions in June, causing blazes in the region to soar.

The World Weather Attribution (WWA) service finds that the month was the hottest, driest and windiest year in the 45-year record.

The team conducted an attribution study to find the “fingerprint” of climate change on these weather conditions.

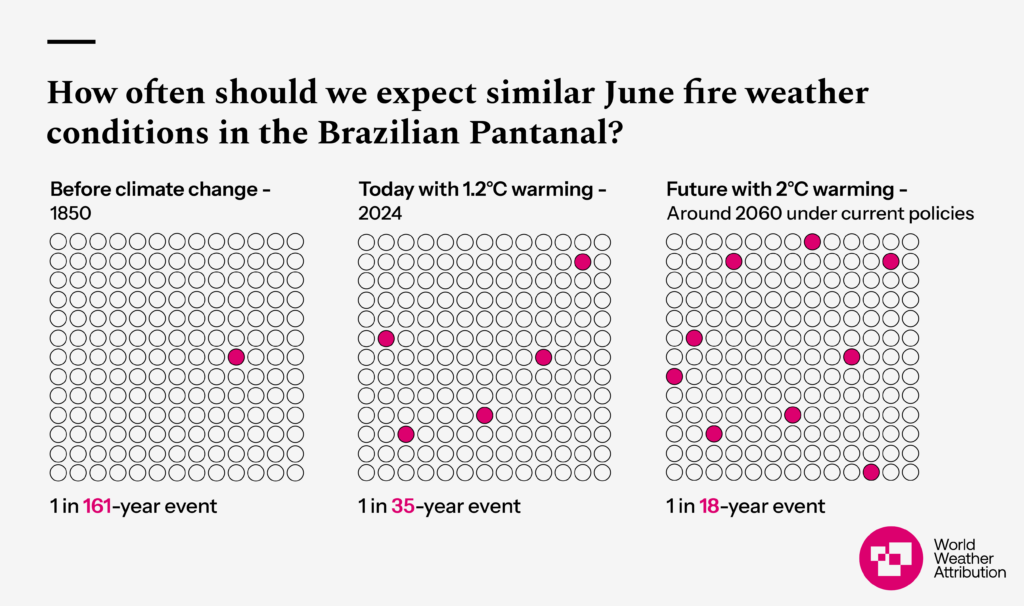

They find that, in a world without climate change, these conditions would be very rare – occurring only once every 161 years.

In today’s climate, which has already warmed by 1.2C above pre-industrial temperatures as a result of human-caused warming, these conditions are a one-in-35 year event.

The authors also explore how wildfires in the region could continue to worsen as the planet warms.

They find that if that planet reaches warming levels of 2C, the likelihood of these conditions could double, to once every 18 years.

Soaring fires

The vast Pantanal wetland extends across Brazil, Bolivia and Paraguay.

It is one of the most biodiverse places on earth, home to more than 4,700 plant and animal species.

Every year, hot and dry weather conditions make the wetland prone to wildfires – usually between July and September.

By June this year, intense wildfires were already soaring. The number of Pantanal fires increased by 1,500% in the first half of this year compared to the same period in 2023, according to data from Brazil’s National Institute for Space Research reported by the Brasil de Fato newspaper.

This amounts to more than 1.3m hectares of the wetland burned so far this year – an area around eight times the size of London.

Around 2,500 fires were identified in June, which is the highest number since 1998 and more than six times the level reported in 2020, which was “known as the ‘year of flames,’ when wildfires ravaged the area and sparked widespread outcry”, the Associated Press said.

The region is currently experiencing its worst drought in 70 years, which Brazil’s government has said is being “intensified by climate change and one of the strongest El Niño phenomena in history”.

Prolonged dry periods, high temperatures and land-use change all contribute to wildfire conditions, says Dr Maria Lucia Barbosa, a postdoctoral researcher at the Federal University of São Carlos in Brazil, who was not involved in the attribution study. She tells Carbon Brief:

“While fires are a natural part of the Pantanal ecosystem, the recurrence of extreme fire seasons – such as the current one, shortly after the devastating 2020 fires – suggests that, alongside climate change, a new fire regime may be emerging in the ecosystem, characterised by increased severity and frequency.”

Hot, dry and windy

Wildfire intensity and duration are influenced by a wide range of factors, including weather, vegetation and fire management strategies.

The authors of the new study focus on a metric called the “daily severity rating” (DSR), which combines information on maximum temperature, humidity, wind speed and precipitation. Dr Clair Barnes – a research associate at Imperial College London’s Grantham Institute and author on the study – told a press briefing that this metric “indicates how difficult it is likely to be to control the fire once it starts”.

High temperatures and wind speeds, as well as low humidity and rainfall, are very conducive to wildfires spreading and, therefore, produce a high DSR.

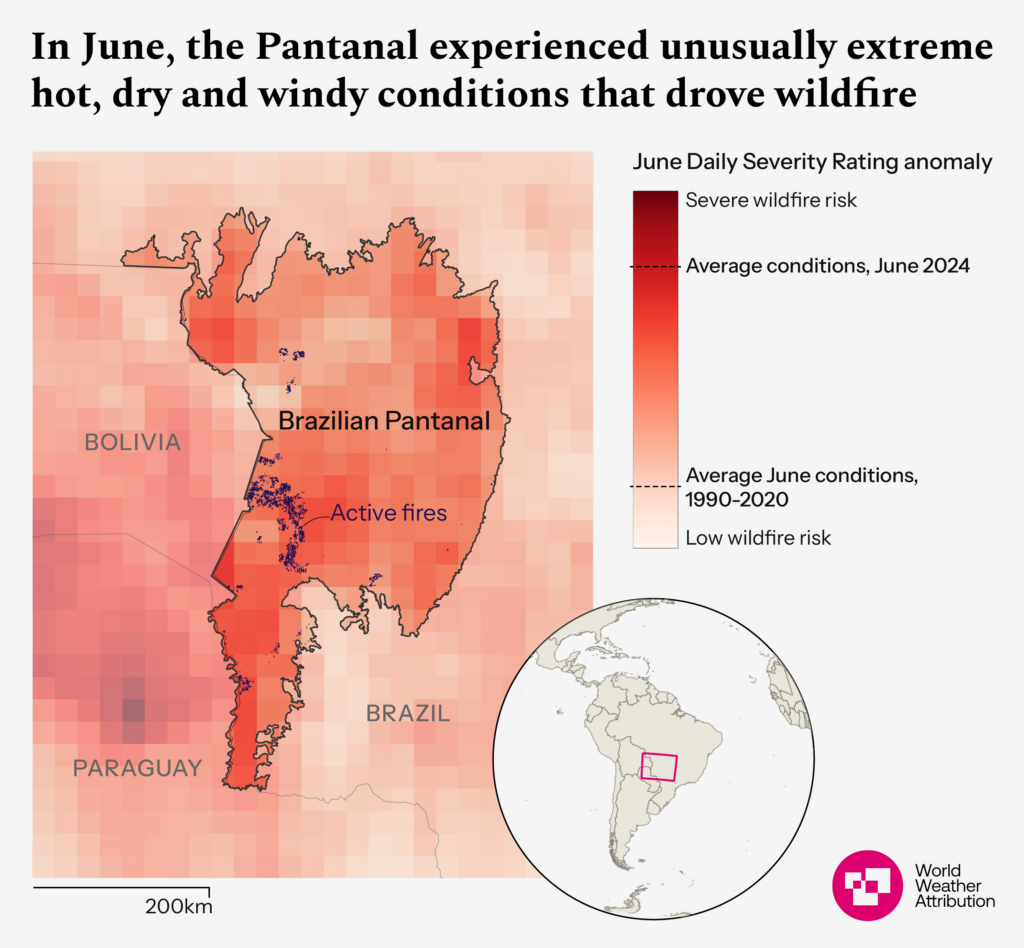

The map below shows the average DSR in the Pantanal in June 2024. It reveals that most of the Pantanal was experiencing wildfire risk above the 1990-2020 average over that month.

The weather conditions in the Pantanal in June 2024 were “really unusual for the time of year”, Barnes said.

To investigate how atypical the weather conditions in June 2024 were, the authors analysed temperature, windiness, rainfall and humidity data from the past 45 years.

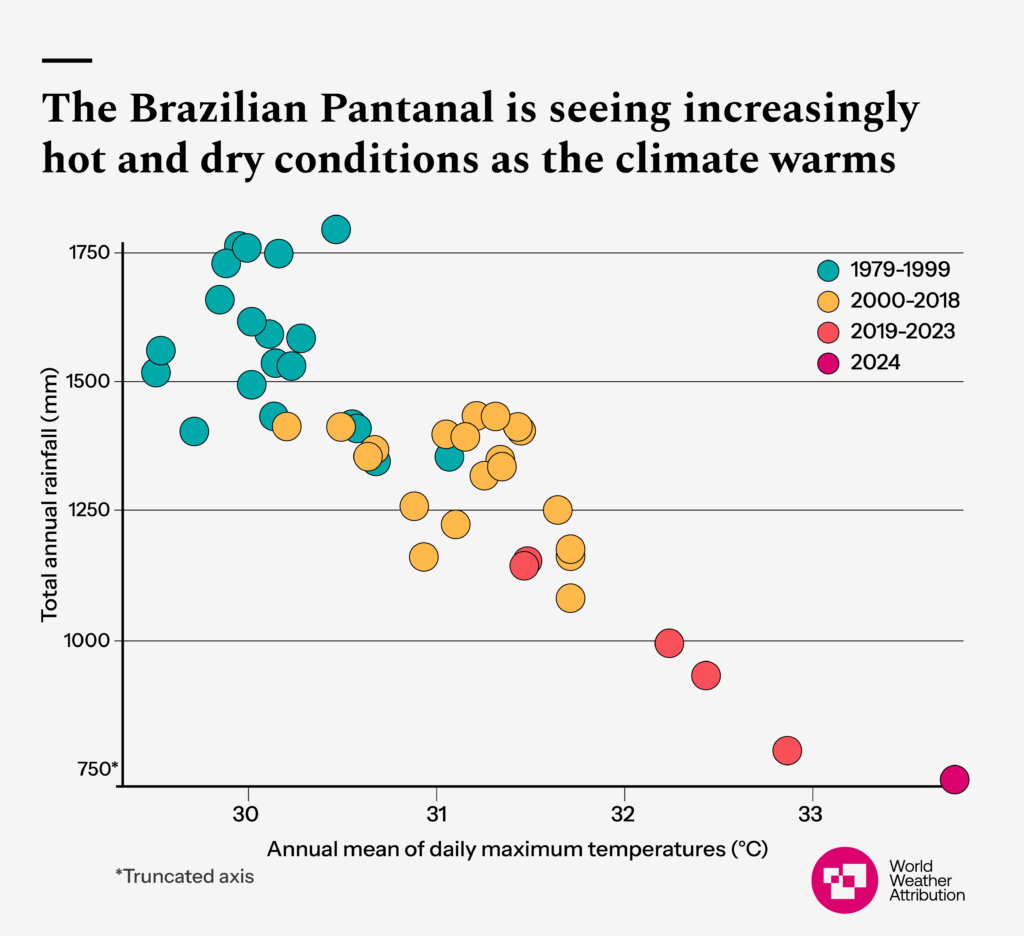

The chart below depicts annual average rainfall and annual average daily maximum temperature in the Pantanal over 1979-2024. It shows that over the past 45 years, the average temperature in the Pantanal has been steadily increasing and total rainfall has been decreasing.

The authors find that June 2024 was the hottest, least rainy and windiest June since records began. They also find that the relative humidity was the second lowest on record.

Annual rainfall across the Pantanal has been decreasing over the past 40 years, the authors note. They point out that natural variability and deforestation are known to impact rainfall patterns across South America, but add that climate change “may also be influencing the drying trend”.

Attribution

Attribution is a fast-growing field of climate science that aims to identify the “fingerprint” of climate change on extreme-weather events, such as heatwaves and droughts.

To conduct attribution studies, scientists use models to compare the world as it is today to a “counterfactual” world without human-caused climate change. In this study, the authors investigated the impact of climate change on DSR in the Pantanal region.

They find that in today’s climate – which has already warmed by 1.2C as a result of human activity – fire weather conditions like the ones that drove the wildfires in the Brazilian Pantanal during June 2024 are a “relatively rare event”, and would be expected to occur roughly once every 35 years.

However, they say, if the planet continues to warm, these events could become more likely. If the climate warms to 2C above pre-industrial levels, the likelihood of these fire conditions will double compared to today.

The graphic below shows how often June fire weather conditions, such as those seen in the Brazilian Pantanal in June 2024, could be expected under different warming levels.

The square on the left shows a world without climate change, in which these DSR levels would happen once every 161 years. The middle square shows that in today’s climate, the DSR is a one-in-35 year event. And the square on the right shows that in a 2C world, a June DSR like that of 2024 could be expected once every 18 years.

The authors also investigate how climate change affected DSR “intensity”. They find that human-induced warming from burning fossil fuels increased the June 2024 DSR by about 40%.

The authors add that as the climate continues to warm, this trend is likely to worsen. The authors warn that if warming reaches 2C above pre-industrial temperatures, similar June fire weather conditions will become 17% “more impactful”.

(These findings are yet to be published in a peer-reviewed journal. However, the methods used in the analysis have been published in previous attribution studies.)

Fire impacts

Wildfires have wide-ranging impacts on people and nature in the Pantanal. In one example, a 2021 study found that around 17m vertebrates were “killed immediately” by the fires in 2020.

Wildfires can “devastate [the] livelihoods” of people living in the Pantanal and “pose significant health risks” from the resulting smoke, Barbosa says.

She notes that wildfires release CO2 into the atmosphere, contributing to climate change, and they “lead to widespread loss of habitat, endanger wildlife and disrupt ecological balances”. She tells Carbon Brief:

“Species that are already threatened or have limited ranges are particularly vulnerable to habitat destruction caused by fires.

“Repeated fires can push fire-sensitive vegetation into a state of permanent degradation, further threatening the ecological integrity of the region.”

Some fires are permitted for agricultural purposes – such as to burn degraded pasture – during the rainy season, from around November to April. This practice is banned in the drier summer months, but a 2020 piece from Mongabay notes that “in reality, the ban is not always respected and enforcement is haphazard”.

Filippe Santos, a researcher at Portugal’s University of Évora and one of the authors of the study, told a press briefing that “fire is part of the dynamics” of the Pantanal – when it is controlled.

Low-intensity fires allow animals “time to leave” the area, he said, adding:

“What we see with wildfires, is that this does not happen, because the fire is so intense and on such a large scale that animals don’t have time to run away.”

The “highly intense” wildfires also “don’t give nature enough time to recover”, Santos says.

In June, Brazil’s environment minister, Marina Silva, told the government news agency Agencia Brasil that the country is “facing one of the worst situations ever seen in the Pantanal”, adding that the fires are heightened by climate extremes and criminal activities.

Most Pantanal fires are caused by human activity, a 2022 study found. Police in Brazil are investigating the “possible culprits” behind 18 fire outbreaks in the region, Silva said last month.

In recent weeks, a law to improve coordination on tackling fires took effect in Brazil.

A statement from the Institute for Society, Population and Nature, a Brazilian NGO, says this new policy is a “significant milestone” and will establish “guidelines for the practice of integrated fire management across all biomes and territories in the country”.

Barbosa says it will be a “challenge” to implement this policy. She would like to see a “comprehensive national early warning system for multiple hazards to ensure risk reduction” for a range of threats – including wildfires. She tells Carbon Brief:

“Collaboration with local communities, firefighters and brigades is crucial for prevention and response efforts…A coordinated approach that integrates all stakeholders, along with the establishment of a national fund dedicated to fire management, is essential for mitigating the impacts of future fire seasons.”

Sharelines from this story