Over the past year, there has been a vigorous debate among scientists – and more broadly – about whether global warming is “accelerating”.

This, in turn, has led to questions about whether the world is warming “faster than scientists expected”.

Here, Carbon Brief takes a detailed look at the issue and finds that there is increasing evidence of an acceleration in the rate of warming over the past 15 years.

However, this acceleration is broadly in line with projections from the latest generation of climate models and the recent sixth assessment report (AR6) from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). They all expect the world to warm notably faster in both current and future decades than the rate the world has experienced since 1970.

Carbon Brief’s analysis also reveals that the speed up in warming projected in the latest climate models (known as CMIP6) is similar to the acceleration estimated by prominent climate scientist Dr James Hansen and colleagues in their much-discussed 2023 paper in Oxford Open Climate Change.

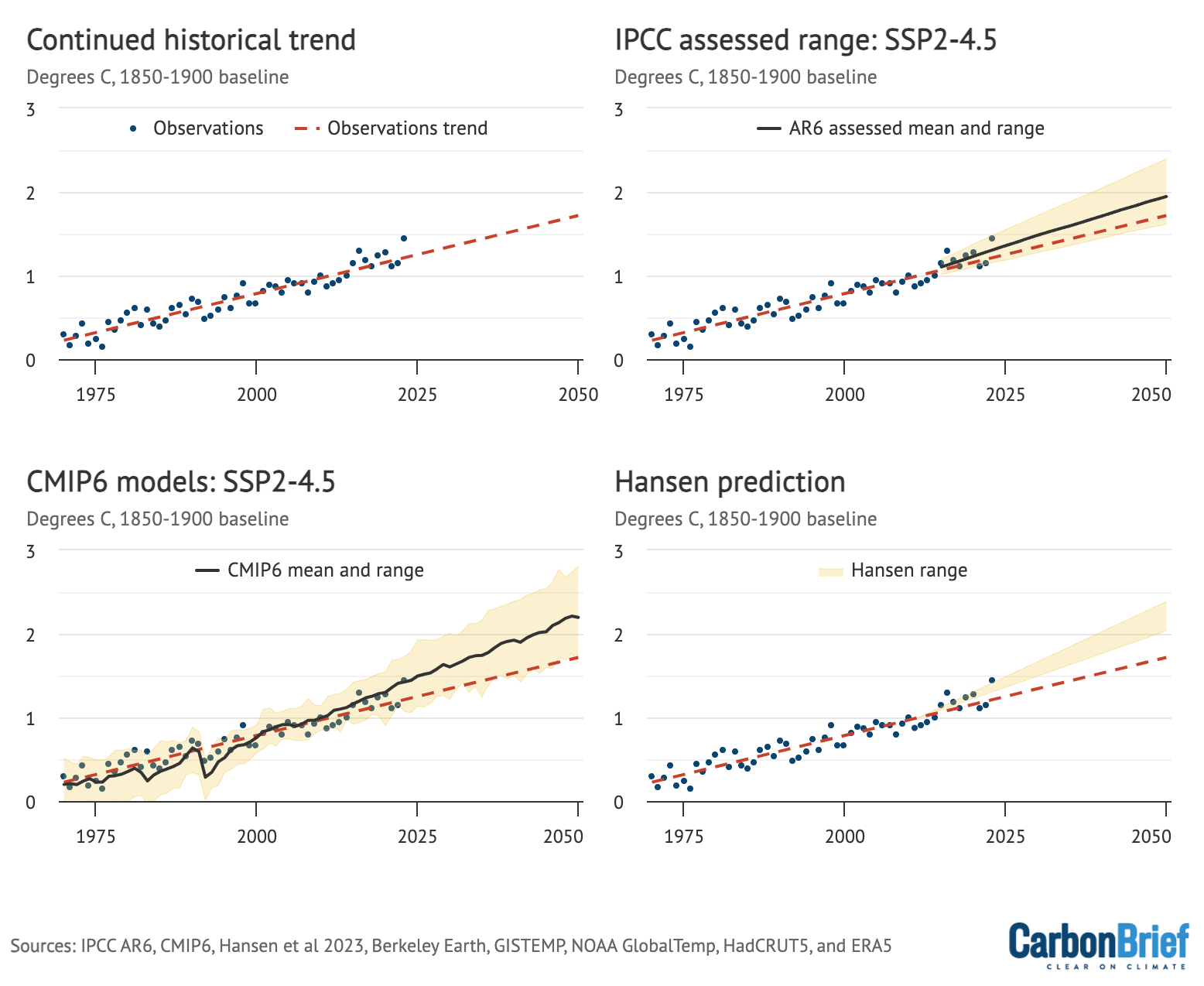

The IPCC’s AR6 also produced a set of “assessed warming projections” that incorporate multiple lines of evidence. While these project future warming levels a bit below the average of CMIP6 models, they still expect the rate of warming up to 2050 to be around 26% faster than the world has experienced to date since 1970.

Even with an apparent acceleration in recent warming, there remain major questions regarding drivers of 2023’s record-breaking heat relative to 2022, though annual temperatures still remain well within the range of climate-model projections.

An accelerating debate

Between 1970 and 2008, the world warmed at an approximately linear rate – by 0.18C per decade.

However, in recent years, the rise in global surface temperatures has climbed above this long-term trend, with eight of the past nine years showing warming levels above what would be expected given the historical warming rate.

In December 2022, former NASA scientist Dr James Hansen and colleagues published a preprint (later published as a peer-reviewed paper in 2023) projecting an acceleration in the rate of warming over the next few decades. Hansen and colleagues argued that the rate of warming would increase to between 0.27C and 0.36C per decade – or a 50-to-100% increase in the warming rate since 1970 – over the next 30 years.

These projections – coupled with the exceptional and unusual temperatures in 2023 – has fuelled a debate within the scientific community and among the broader public about a potential acceleration in warming in recent years.

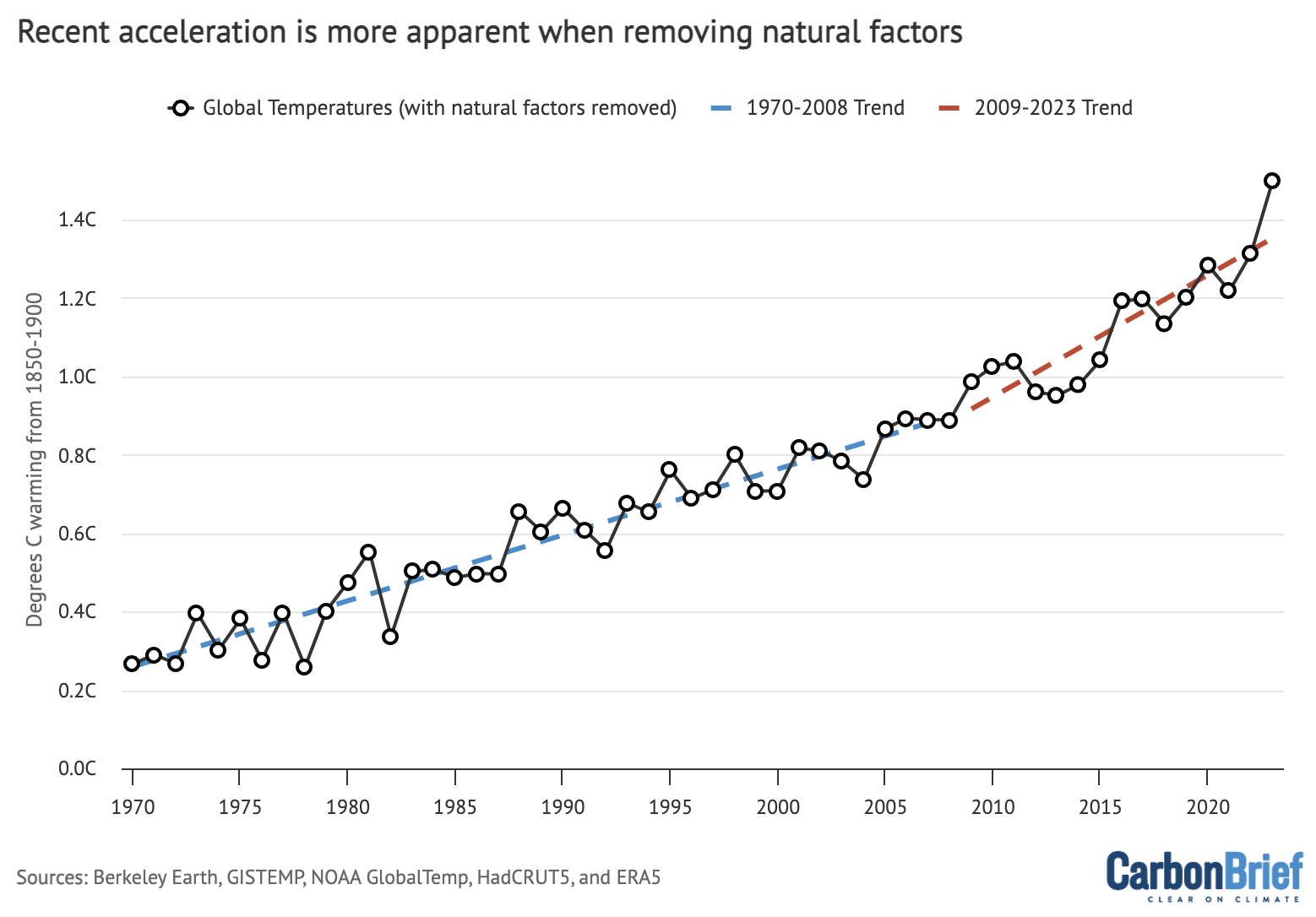

This potential acceleration is illustrated in the figure below, which shows a composite of global surface temperatures from five different groups – NASA GISTEMP, NOAA’s GlobalTemp, the UK Met Office/University of East Anglia’s HadCRUT5, Berkeley Earth and Copernicus’ ERA5 – following an approach used by the World Meteorological Organization.

The circles indicate individual years and the dashed lines show the trend over 1970-2008 (blue) and 2009-23 (red). (The past 15 years are highlighted here as that is the time period that has previously been used to assess potential changes in the underlying trend in the scientific literature.)

Annual global average surface temperatures from a composite of NASA GISTEMP, NOAA’s GlobalTemp, the UK MET Office/UEA’s HadCRUT5, Berkeley Earth, and Copernicus’ ERA5 following an approach used by the World Meteorological Organization, with linear trends between 1970 and 2008 (blue) and 2009 and 2023 (red) shown by the dashed lines. Chart by Carbon Brief.

The chart shows how the warming rate of 0.18C per decade seen since 1970 has almost doubled to roughly 0.3C per decade over the past 15 years.

Researchers have proposed a number of potential contributors to the increased rate of warming seen in recent years.

One is the significant decline in global air pollution over the past few decades, as well as a 2020 phase-out of sulphur in marine fuels, which have reduced the levels of cooling aerosols in the atmosphere.

Other suggested factors include an approaching peak in the 11-year solar cycle, the 2022 eruption of the Hunga Tonga volcano and the continued increases in atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations.

The fact that the past 15 years ended on a particularly high point due to the current El Niño event might also result in higher warming rates – although the contribution of El Niño to overall 2023 temperatures remains an area of vigorous scientific debate.

It is possible to remove the estimated influence of some of the natural factors – such as El Niño and La Niña events, volcanic eruptions and variations in solar output – from the global temperature record.

The figure below shows a version of the temperature record above where these natural factors are removed. The recent warming (red dashed line) is even more evident in this chart compared to the prior trend (blue).

Composite of five annual global average surface temperature records with the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO), volcanic eruptions and solar variations removed. Linear trends between 1970 and 2008 (blue) and 2009 and 2023 (red) shown by dashed lines. Data from Tamino following an updated version of the methodology in Foster and Rahmstorf 2011. Chart by Carbon Brief.

However, despite this spate of very warm years, it is challenging to draw firm conclusions on the overall rate of global warming based on a time period as short as 15 years.

Even though recent trends appear to show significant acceleration, the long-term trend remains – just barely – within the full range of uncertainty in climate model projections.

There is a risk of conflating shorter-term climate variability with longer-term changes – a pitfall that the climate science community has encountered before.

Parallels with the warming ‘hiatus’

The debate around a potential acceleration in warming shares similarities with another scientific contretemps – the so-called “hiatus” in warming of the early 21st century.

During the 15-year period from 1998 to 2012, the rate of warming at the surface appeared to nearly “pause” – or at least slow down dramatically compared to climate-model projections.

The debate so consumed the scientific community – and some sections of the media – that there was a running joke among scientists that the journal Nature Climate Change should be renamed “Nature Hiatus” for the number of studies it published trying to explain the apparent slowdown.

In retrospect, the apparent hiatus and associated disagreement between climate models and observations was caused by a number of different factors. Key among them were natural variability (in the form of more heat uptake by the oceans), disparities in surface temperature records associated with a transition from ship engine room to automated buoy-based measurements of sea surface temperatures, and incomplete comparisons between climate models and observations that excluded areas such as the Arctic that had sparser observational coverage.

With the development of the 2015-16 “super” El Niño, any sign of a “pause” in warming quickly vanished and the argument faded away – though it made a brief return in climate-sceptic circles in more recent years. However, it left behind a lasting appreciation among many scientists for the danger of overinterpreting short-term climate variability and is one of the reasons why there has been reticence in some circles about current claims of an acceleration.

Nonetheless, there are a number of reasons to expect that what the world is currently experiencing is not just the influence of natural variability on top of human-caused warming. An acceleration of warming in recent decades also shows up in ocean heat content and in satellite measurements of the Earth’s energy imbalance.

And, perhaps most importantly, an acceleration in the rate of warming in recent years – and over the coming decades – is exactly what is seen in climate models under a scenario in keeping with current global policies (known as SSP2-4.5). Under this scenario, greenhouse gas emissions remain around current levels until the middle of the century, alongside a decline in emissions of planet-cooling aerosols such as sulphur dioxide.

An expected acceleration

The most notable thing about the current apparent acceleration in warming is that it was expected.

Climate models have long shown a faster rate of warming in current and future decades than has been observed to date, though there is some disagreement among modelling estimates.

The table below shows a compilation of both observed rates of warming to date and different model projections out to 2050.

| Projection | Time period | Trend (C/decade) |

|---|---|---|

| Observed trend since 1970 | 1970-2023 | 0.19 (0.17 to 0.21) |

| Observed trend since 2009 | 2009-2023 | 0.30 (0.17 to 0.43) |

| Estimated human contribution (Forster et al, 2023) | 2013-2022 | 0.23 |

| IPCC AR6 assessed warming projections under SSP2-4.5 | 2015-2050 | 0.24 (0.17 to 0.34) |

| Full CMIP6 ensemble under SSP2-4.5 | 2015-2050 | 0.29 (0.2 to 0.4) |

| Hansen et al, 2023 | 2011-2050 | 0.32 (0.27 to 0.36) |

Global surface temperatures have warmed at a rate of 0.19C per decade between 1970 and 2023. They have warmed at a faster rate (~0.3C per decade) over the past 15 years – though with large uncertainties of 0.17C to 0.43C given the shorter time period.

The estimated human contribution to global warming of 0.23C for the past decade (2013 to 2022), as published in Earth System Science Data by Prof Piers Forster and colleagues, is based on a climate model emulator that is driven by an updated estimate of factors including the influence of greenhouse gases and aerosols on the Earth’s climate in recent years.

The IPCC’s AR6 provided “assessed warming projections” based on CMIP6 models – weighted based on their ability to accurately reproduce historical temperatures – and the recent synthesis of climate sensitivity estimates. These assessed warming projections show 0.24C warming per decade between 2015 and 2050 with an uncertainty range of 0.17C to 0.34C in the current-policy-type SSP2-4.5 scenario. This represents approximately 26% faster warming than the world has experienced since 1970.

The full CMIP6 ensemble of models has notably more warming than the IPCC-assessed warming projections. CMIP6 models, on average, warm by 0.29C per decade with a range of 0.2C to 0.4C, or 53% faster than historical warming since 1970.

The recent projections by Dr James Hansen and colleagues has a very similar projection of future warming rates to the CMIP6 ensemble, estimating warming of around 0.32C per decade with an uncertainty of 0.27C to 0.36C.

These estimates are summarised in the charts below, which show the historical warming rate (top left), the AR6 assessed range under SSP2-4.5 (top right), the CMIP6 models under SSP2-4.5 (bottom left) and Hansen et al’s future warming projection (bottom right). The blue dots and red dashed lines show observed data and the long-term trend, while the black lines and yellow shading show the average of model projections and their ranges.

Comparison of historical and future warming projections from a continuation of the 1970-2023 linear trend (top left), the IPCC AR6 assessed warming range for SSP2-4.5 (top right), the CMIP6 multimodal mean and range for SSP2-4.5 (bottom left) and Hansen et al 2023 (bottom right). Blue dots and red dashed lines show observations and trends, while the black lines and yellow shading show model projections and their ranges. Chart by Carbon Brief.

In all three cases, there is an expectation of acceleration of warming both at present and in coming decades compared to the warming the world has experienced since 1970.

However, this does not mean that the world will pass climate limits such as 1.5C sooner than expected. The current best estimates of when these thresholds will be passed are based on climate models that include the near-term warming acceleration.

The apparent acceleration of warming in recent years is well in line with climate model projections, which lends confidence that what the world is experiencing is a result of human activity rather than a result of natural variability.

However, this does not mean that the world will not experience cool years in the future; the next La Niña year – likely in 2025 – will probably end up well below some of the prior record-setting years.

But, as long as global emissions of CO2 and other greenhouse gases fail to decline and the world continues to tackle aerosol pollution, the world will likely warm faster than experienced in the past.

Sharelines from this story