Over the past 10 years, the global energy transition away from coal has accelerated. The number of countries with coal power under development (pre-construction and construction) has nearly halved from 75 in 2014 to just 40 in 2024.

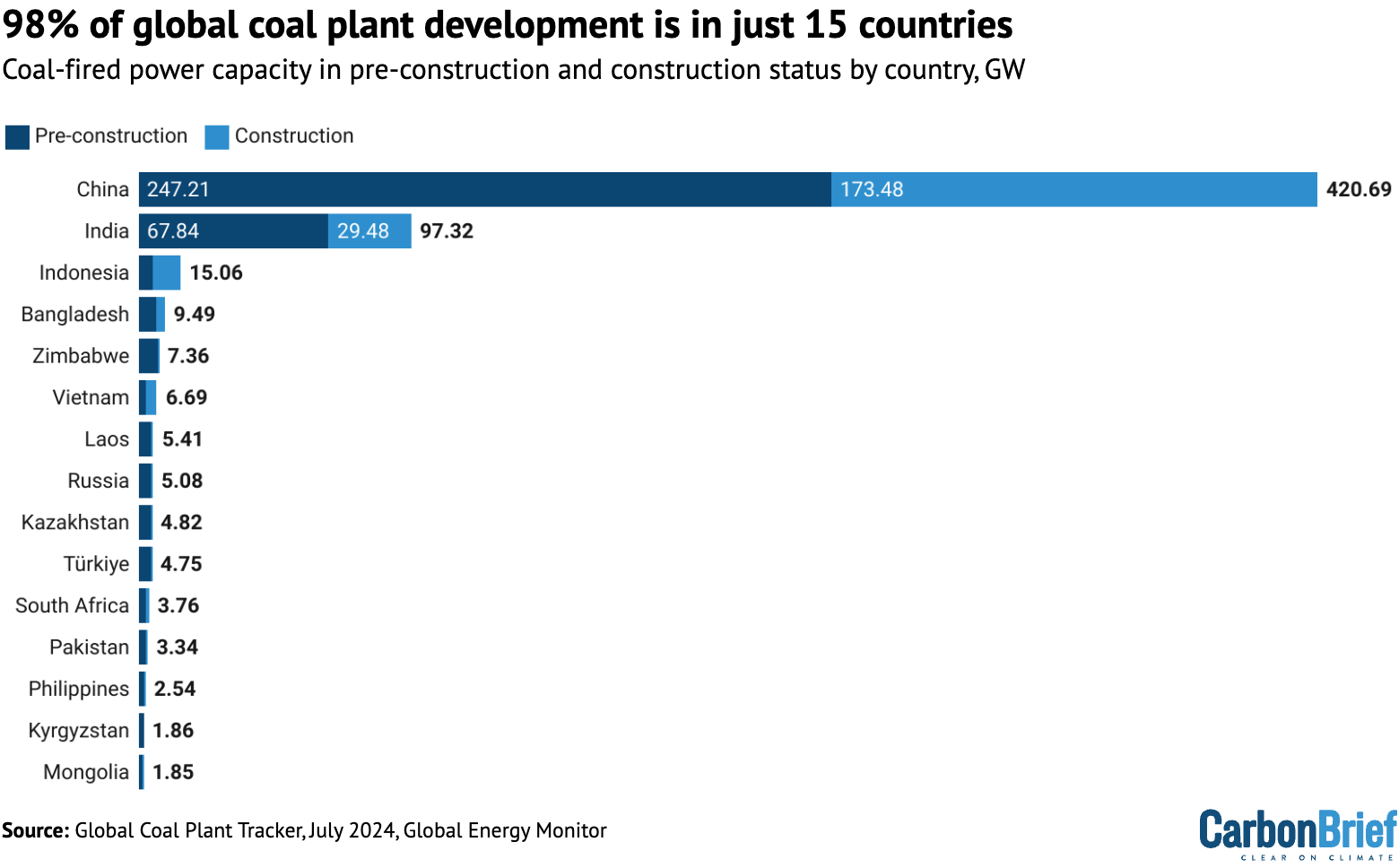

In addition, nearly all of the coal-power capacity under development (98%) is now concentrated in just 15 countries, with China and India alone accounting for 86%.

This is according to Global Energy Monitor’s latest Global Coal Plant Tracker (GCPT) results, completed in July 2024. The GCPT catalogues all coal-fired power units 30 megawatts (MW) or larger biannually, with the first survey dating back to 2014.

Despite the concentration of coal-plant development in fewer countries and projections that global coal demand could be peaking, new coal-fired power station proposals continue to outpace cancellations.

In the first half of 2024, over 60 gigawatts (GW) of coal capacity was newly proposed or revived, compared to the 33.7GW that was shelved or cancelled over the same period.

This article details some of the most significant trends driving the continued development of coal across the 15 largest markets, drawing insight from the GCPT, as well as wider context.

Global overview

Over the first six months of 2024, nearly twice as much coal capacity was proposed as was shelved or cancelled, as coal-fired capacity continues to grow globally.

This rebound in proposals is largely due to a resurgence beginning in China in 2022, followed by India in 2024. In fact, as shown in the figure below, almost all (97%) of the new and newly revived proposals in the first half of 2024 are located in China and India.

Additionally, of the 1.8GW of newly proposed capacity in the rest of the world, more than 40% is sponsored by Chinese companies.

Our results show that the elimination of new coal plants – a crucial step toward the rapid reduction in coal power use needed to keep global warming below 1.5C – is increasingly dependent on a shrinking number of countries.

The signing of the Paris Agreement in 2015 kick-started momentum in the global shift away from coal. To date, 75 countries have established carbon neutrality goals for 2050 or earlier, and over 100 countries are coal-free or have an established coal phaseout date in 2040 or earlier.

This growing number of commitments has been accompanied by a steep drop in coal capacity under development globally – the amount that has been announced, entered the permitting process, been granted a permit or started construction.

This pipeline of coal under development has declined by 62% compared to a decade ago, from 1,576GW in 2014 to 604GW today, according to the latest data from the GCPT

As shown in figure below, 590GW of that 604GW is concentrated in a handful of countries, dominated by China (70%) and India (16%). The other 14GW (not shown below), or 2% of the total capacity, is spread across 25 countries, each with less than 1.5GW under development.

Despite the decline, some countries have not yet set energy transition targets consistent with the Paris Agreement or the UN’s 2023 “acceleration agenda”, which calls for the termination of all remaining coal proposals and a total phaseout of coal power by 2040.

The first global stocktake, drafted at the December 2023 COP28 conference, “urges” the similar but less aggressive global “phase-down of unabated coal power”.

Currently, though, none of the fifteen countries leading continued coal plant development have an established coal phaseout target.

While Indonesia, Vietnam and South Africa have negotiated “just energy transition partnership” (JETP) agreements to transition away from coal, their plans still allow for some growth in coal power.

The JETP agreements have also yet to resolve several thorny issues, such as how to treat “captive” coal plants that supply electricity off-grid, typically to large industrial sites. Increased JETP ambitions could help these countries achieve Paris-aligned emissions reductions.

China is involved in coal development in Indonesia, Zimbabwe, Laos, Kyrgyzstan and Mongolia, including some capacity proposed after China’s 2021 pledge to stop building new coal plants abroad. Apparent exceptions to the 2021 moratorium have emerged for projects designed for captive use or proposed as expansions at existing China-backed projects.

Meanwhile, many new coal proposals in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan have Russian backing.

Several countries, including Bangladesh, Pakistan, the Philippines and Turkey are continuing with plans to develop a backlog of proposed coal plants in the face of counteraction to the fuel, such as local opposition, policy changes, finance moratoriums and other challenges.

The latest developments in each of these 15 countries are detailed below. The countries are listed in order, starting with the largest capacity of new coal under development, in China. Each includes a map that provides a snapshot of the coal-fired power plants under development, for the full data behind each see the GCPT database.

Back to top

China

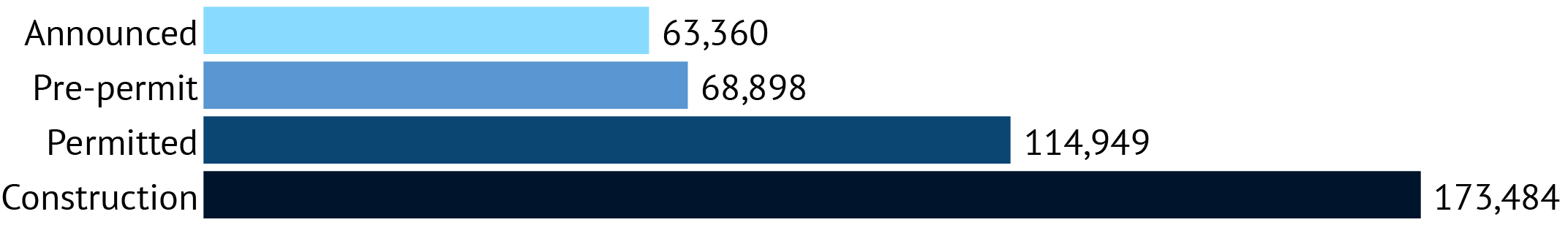

Total planned capacity, GW

China’s dominance in the global energy landscape is underscored by its enormous coal power capacity.

As of June 2024, the country had 1,147GW of operational coal capacity spread across nearly 3,200 units, representing more than half (54%) of the world’s total operating coal capacity.

For years, China has led coal power development, but the pace of this development showed notable signs of an incoming slowdown in the first half 2024.

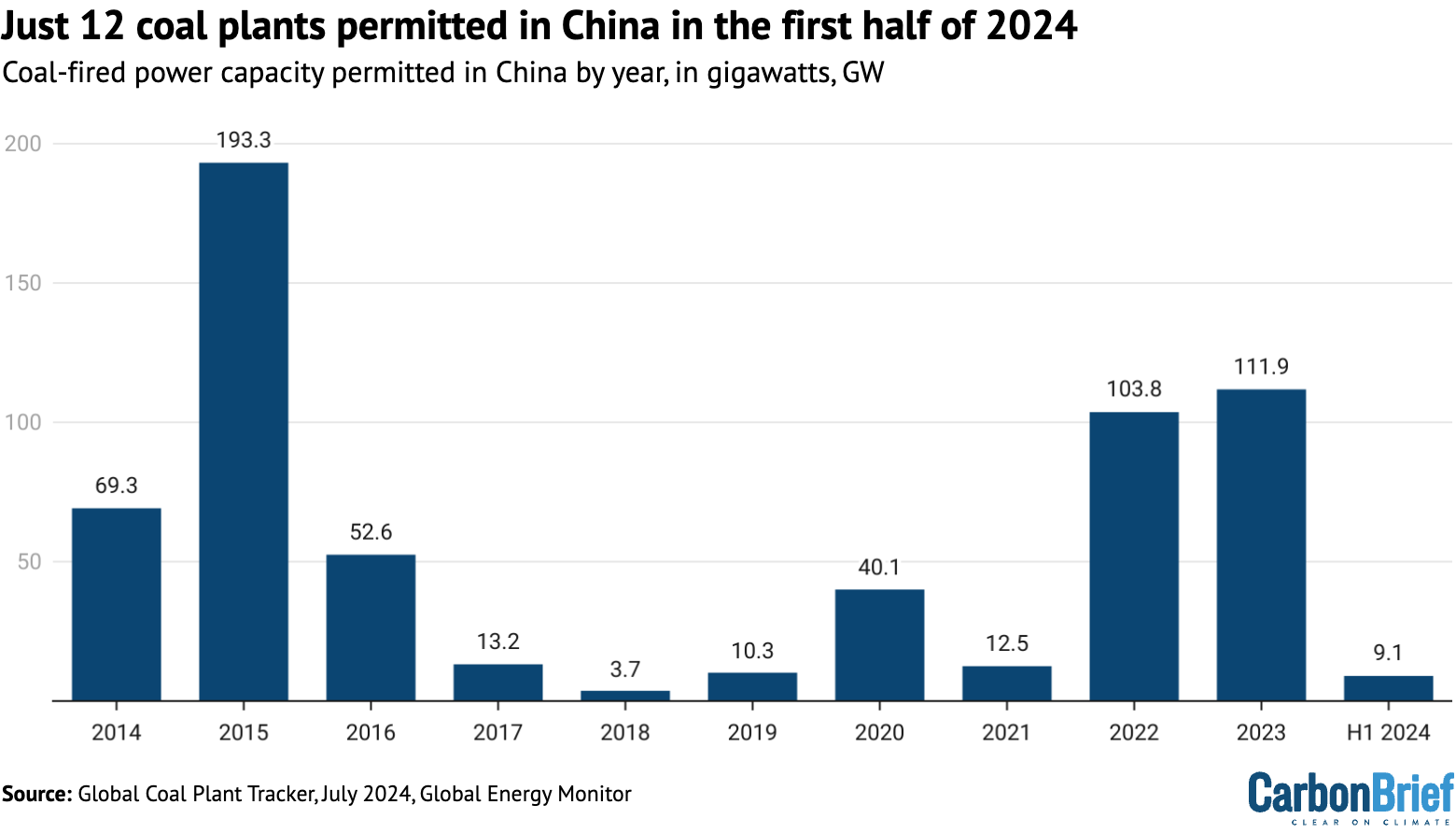

Following the recent spate of permitting of coal projects, exceeding 100GW annually in 2022 and 2023, China has made a sudden pivot.

The country drastically reduced approvals for new coal power in the first half of 2024, granting permission to only twelve projects totaling 9.1GW, as shown in the figure below.

The newly permitted capacity is equivalent to just 8% of what was permitted in all of 2023 and 17% of the peak half-year capacity permitted in the second half of 2022.

Notably, some of these permitted projects were expedited. For example, the extension of the Harbin No. 3 power station was initiated in April 2024 and then permitted for construction just two months later.

In 2024, proposals for new and revived coal projects are also showing a downward trend compared to the peak years of 2022 and 2023, with 38.1GW of new and revived proposals in the first half of the year, compared to 60.2GW in the first half of 2023 and 47.8GW in the first half of 2022.

This trend hints at a potential slowdown in new project development, albeit not as pronounced as the permit slowdown.

GEM’s analysis indicates that the deceleration of coal project announcements and permitting is likely the result of China’s massive clean energy deployment. By the end of June 2024, the total grid-connected wind and solar capacity reached 1,180GW, making up 38.4% of the total installed power generation capacity in the country and overtaking coal (38.1%) for the first time in history.

In 2024, renewable power growth was evenly balanced against electricity demand growth, according to the China Electricity Council (CEC). As such, coal is beginning to shift into a supporting role, GEM analysis suggests.

Despite the slowdown in permitting, there is still a substantial overhang of new coal capacity permitted during 2022 and 2023.

Indeed, construction activities in the first half of 2024 were robust, with over 41GW of projects initiated, nearly matching the 2022 full-year total. In addition, over 8.6GW of coal power entered operation in the first half of 2024.

Moreover, the Chinese government has a target of commissioning 80GW of coal capacity in 2024, suggesting a potential surge in the second half of the year.

If even half of that capacity is commissioned in 2024, it would be a clear indication of the coal industry’s resilience and momentum despite the decreasing need for new coal power, our research suggests.

Coal plant retirements in China remain low, with only 1.1GW of coal capacity taken offline in the first half of 2024. From 2021 to 2024, China retired 9.8GW of coal capacity and mothballed 2.5GW, not including capacity at units smaller than 30MW.

China must remove 17.7GW of capacity from its coal power fleet in the next 18 months if it wants to fulfil its promise to shut down 30GW of coal power during the 14th ‘five year plan’ period.

Back to top

India

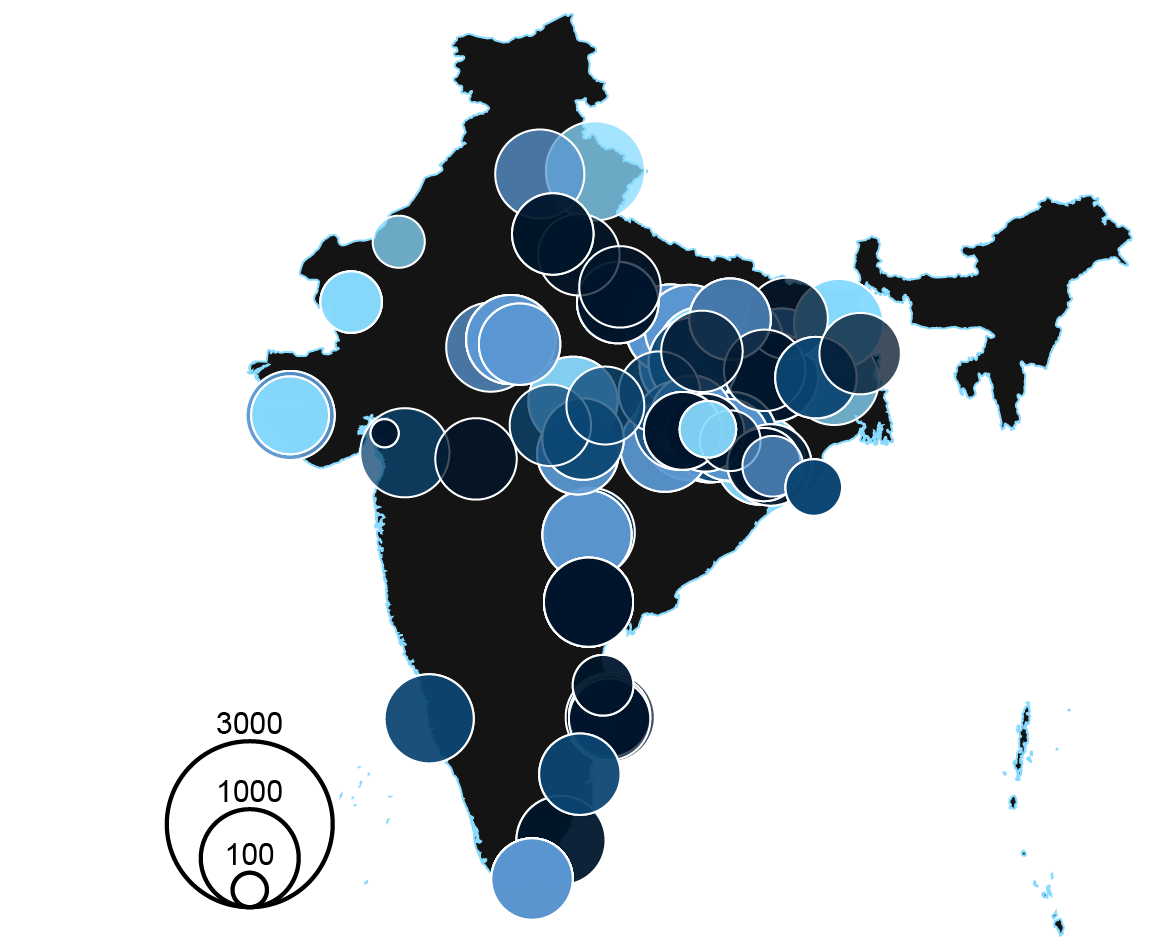

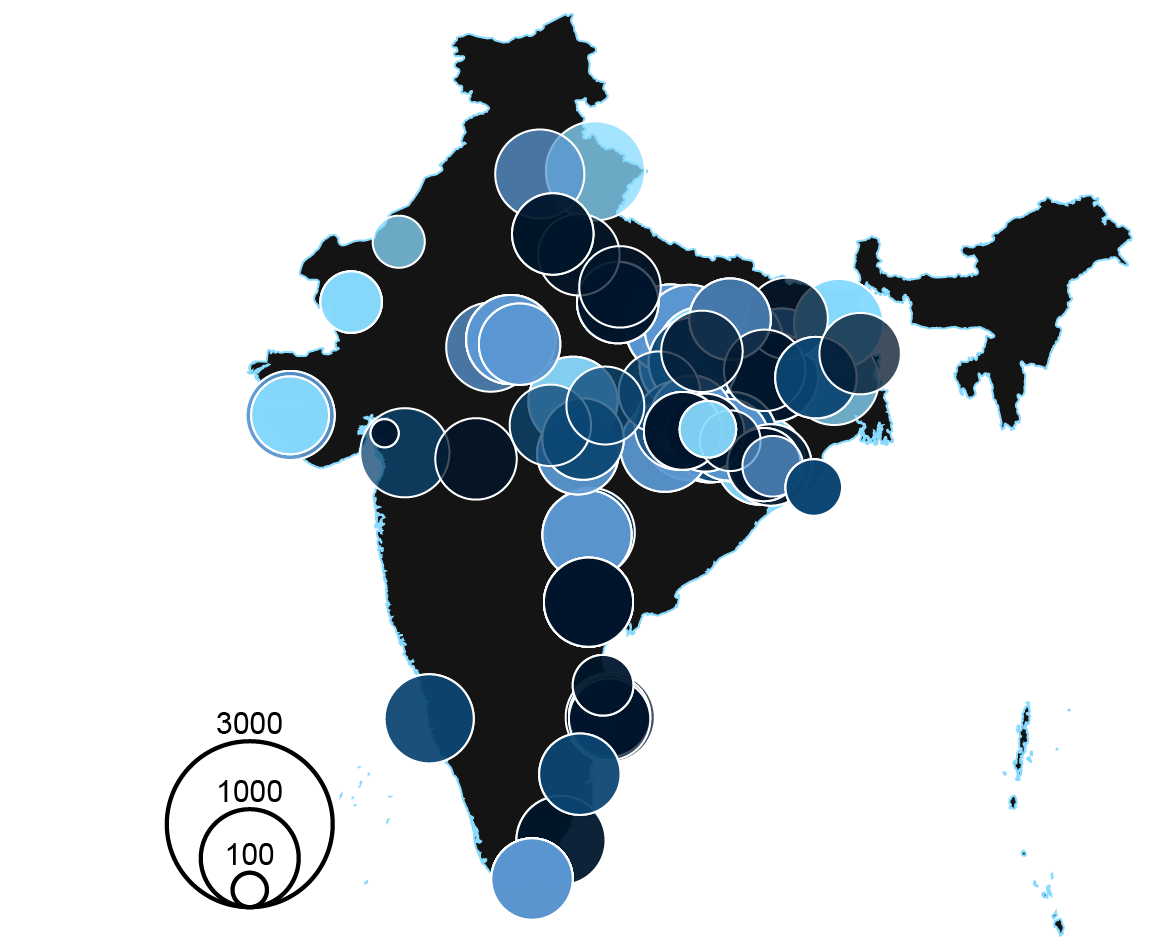

Total planned capacity, GW

India’s coal fleet is the second largest in the world after China, totaling 239.6GW, according to the GCPT.

While the country’s electricity mix continues to be dominated by coal, renewable energy additions recently pushed coal below 50% of installed capacity for the first time.

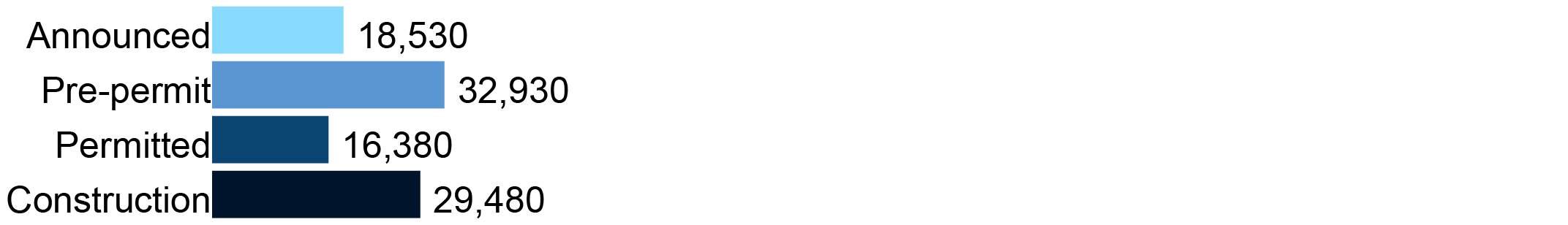

At the same time, the development of new coal plant proposals has shown no sign of slowing down, the GCPT shows. To the contrary, India’s coal plant development ballooned in the first half of 2024.

Increasingly severe climate-forced heatwaves continue to drive up electricity demand in India, most recently culminating in a new peak power demand of 246GW, reached in May 2024.

Both coal power generation and carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions in the power sector saw a 10% increase from January 2023 to January 2024.

Citing the increased power demand, the Indian government has encouraged and fast-tracked the development of large coal plants by predominantly publicly-financed, state-owned entities – despite analyses showing that India could meet its growing demand by achieving its renewable energy targets.

In the first half of 2024 alone, the capacity of new and revived coal plant proposals (23.5GW) has already surpassed all of 2023 (13.6GW). This increased the total coal capacity under development from 76.7GW in 2023 to 97.3GW in the first half of 2024, as shown in the figure below.

In fact, newly proposed coal capacity in just the first half of 2024 is greater than any other full year’s total capacity of new proposals in India since at least 2014, when the GCPT began data collection.

Many of these proposals are large expansion projects opposed by the local population due to displacement and pollution impacts.

One such project is the proposed Kawai power station expansion, announced in early 2024, which would add a substantial 3.2GW to the existing 1.3GW plant. At another, the controversial Mahan Super Thermal power project – whose development affected the livelihood of an estimated 14,000 people – Indian multinational Adani Power has begun construction on two expansion units, and the Indian government has given preliminary approval for two additional units.

India is now catching up to China with new coal capacity proposals, the country long considered to be the isolated global leader in continued coal plant development. In the first half of 2024, India’s 23.5GW of newly proposed coal capacity was nearly two-thirds that of China (38.1GW), compared to just 7% in 2021.

With prime minister Narendra Modi securing his third term in India’s early 2024 election, ongoing expansion of coal and opposition to developing a long-term coal phaseout plan are likely to persist. While India’s coal plant development surges, the retirement of ageing and inefficient coal plants in India remains near zero.

Back to top

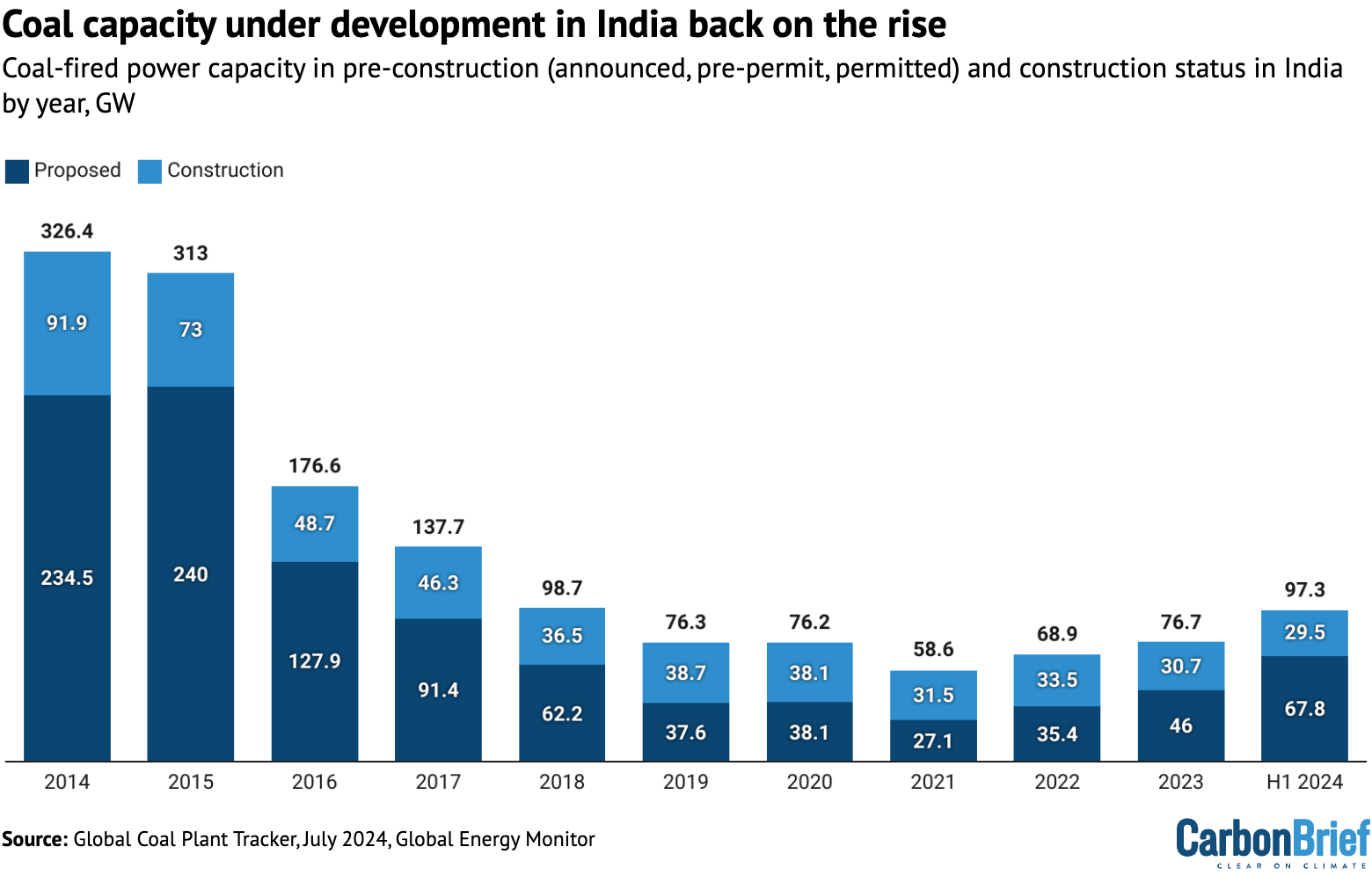

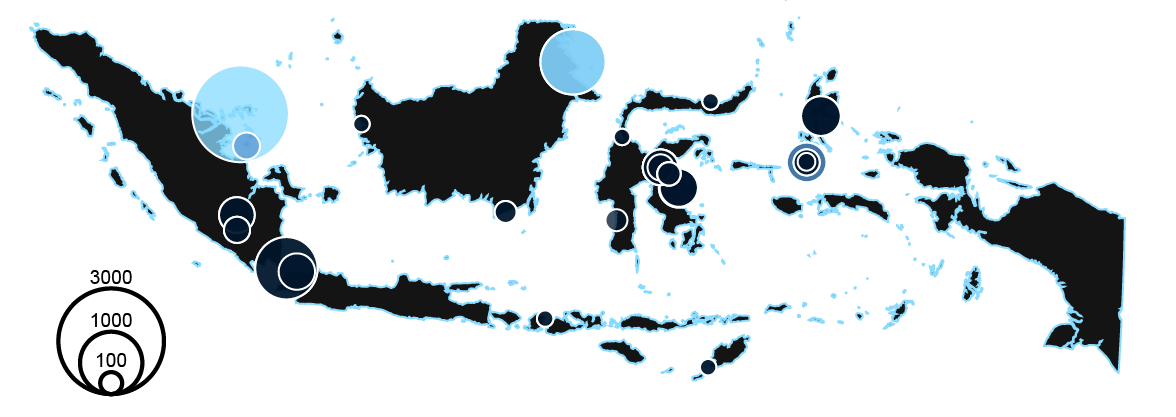

Indonesia

Total planned capacity, GW

Indonesia continues to be the biggest coal exporter in the world, and the country plans to increase coal production and consumption in 2024 and beyond.

Indonesia’s coal capacity under development has diminished by over 70% in the last decade, down to 15.1GW from 55.9GW in pre-construction or construction in 2014.

Still, in addition to having the third-largest coal capacity under development globally, Indonesia faces several unique challenges to a successful transition away from coal.

Indonesia’s JETP agreement, which is designed to aid the country in prioritising alternative sources of energy, has faced unexpected challenges in the first half of 2024.

This follows the December 2023 omission of captive coal plants from emissions projections for the JETP comprehensive investment and policy plan.

Indonesia’s significant captive coal-fired capacity, both operating and under development, could lock the country – and its booming metal processing sector – into long-term coal use.

Over 1GW of coal-fired capacity entered construction in the first half of 2024, and over 40 total units are now under construction in the country, according to the GCPT. Additional captive coal capacity continued to be proposed in Indonesia in 2024, despite growing international opposition to the trend.

This opposition is particularly seen when the electricity is slated for use in ostensibly “green” manufacturing projects, such as Adaro’s proposed aluminium processing facility in North Kalimantan, Indonesia and the expansive Weda Bay nickel processing facility in North Maluku, Indonesia.

There is resistance to proposals such as the Xinyi Group captive power station over public health, environmental and human rights concerns. Moreover, multilateral development banks have pledged not to fund new coal power projects.

Yet policy loopholes mean some continue to indirectly finance captive coal plants in Indonesia.

Captive coal also seems to be a caveat to China’s 2021 overseas coal plant moratorium, with Chinese entities continuing to participate in Indonesia’s captive coal industry.

Several on-grid projects also remain under construction, with some of this capacity fully constructed but not yet operating due to grid overcapacity, such as Unit 4 of the Banten Lontar power station.

Indonesia faces a grid connectivity issue across its thousands of islands, with some provinces over-generating and others under-generating without the necessary electricity transmission infrastructure to link them.

The country held a presidential election in February 2024, with Prabowo Subianto certified as the president-elect in March. Prabowo has known business interests in coal and other fossil fuels and has been called to divest from these companies before taking office in October 2024.

According to statements released during his election campaign, Prabowo’s five-year plan for the energy sector included intentions to expand the use of renewable energy sources but did not mention coal plant retirements or an end to new coal proposals.

But, the incoming administration will be tasked with reconciling the captive emissions problem and setting clear plans for the country’s long-term energy strategy in order for the JETP agreement with international partners to advance.

Back to top

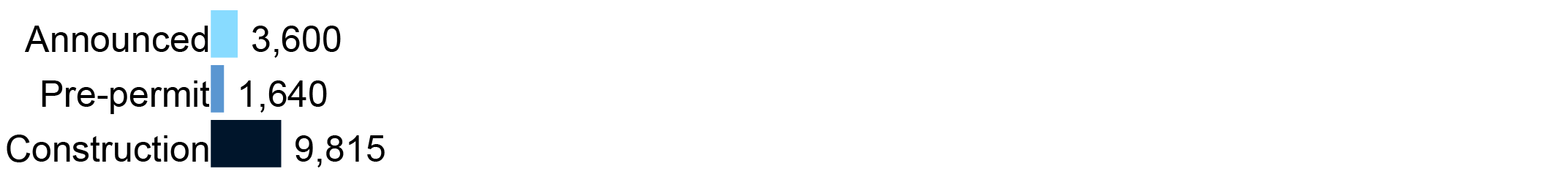

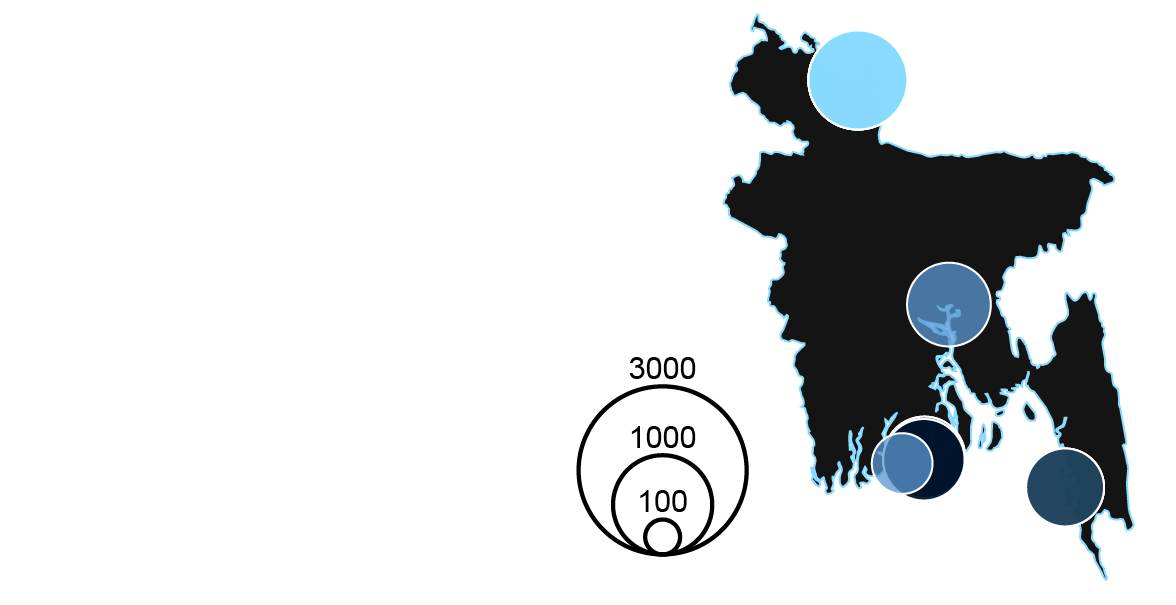

Bangladesh

Total planned capacity, GW

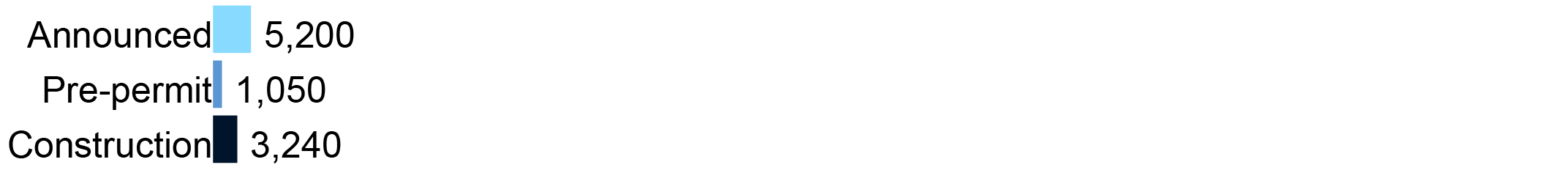

Bangladesh ranks fourth in the world for coal power under development, with 6.3GW proposed and 3.2GW under construction as of June 2024, according to the GCPT.

While coal generation more than doubled from 2022 to 2023, Bangladesh has not announced any new coal plant proposals since 2019. A suite of problems continue to plague the fuel, further complicated by political unrest throughout the country in July and August 2024.

These problems include an ongoing dollar shortage, the high cost of imported coal and a buildup of unpaid electricity bills, which intensified a nationwide power crisis in the first half of 2024, leading to fuel supply gaps and load shedding, despite sufficient power capacity.

For example, at the Matarbari power station, Coal Power Generation Company Bangladesh had yet to receive payment for power supplied to the national grid from the plant’s operating coal unit from December 2023 to May 2024. The company is nevertheless seeking to finance an expansion at the power station, after losing the project’s original funding in 2022, when its sponsor, Japan, pledged to stop publicly funding new coal.

At S. Alam’s Banshkhali power station, units that had completed construction by late 2023 were still not operating at full capacity in February 2024, due to grid constraints.

The country saw just 0.7GW of coal power come online in the first half of 2024 at the contested Rampal power station, against 1.3GW of planned coal capacity cancelled in the same period.

In March 2024, a planned mine associated with the Phulbari power station – a fiercely contested project that has been proposed in various forms for decades and has resulted in the death of at least three protestors – secured a $1bn funding agreement with PowerChina.

Though the power station was not included in this initial financing agreement, China has not explicitly ruled out funding the plant, despite its 2021 pledge to stop building new coal plants abroad. The project sponsors say that they expect the coal plant proposal to “become attractive” due to their proximity.

Back to top

Zimbabwe

Total planned capacity, GW

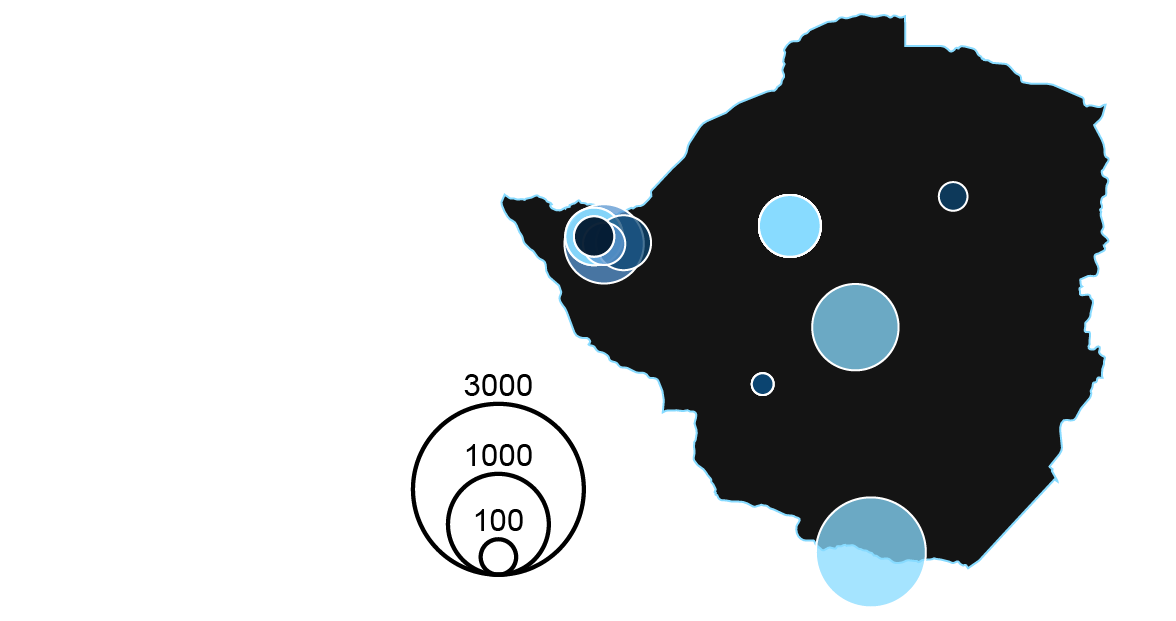

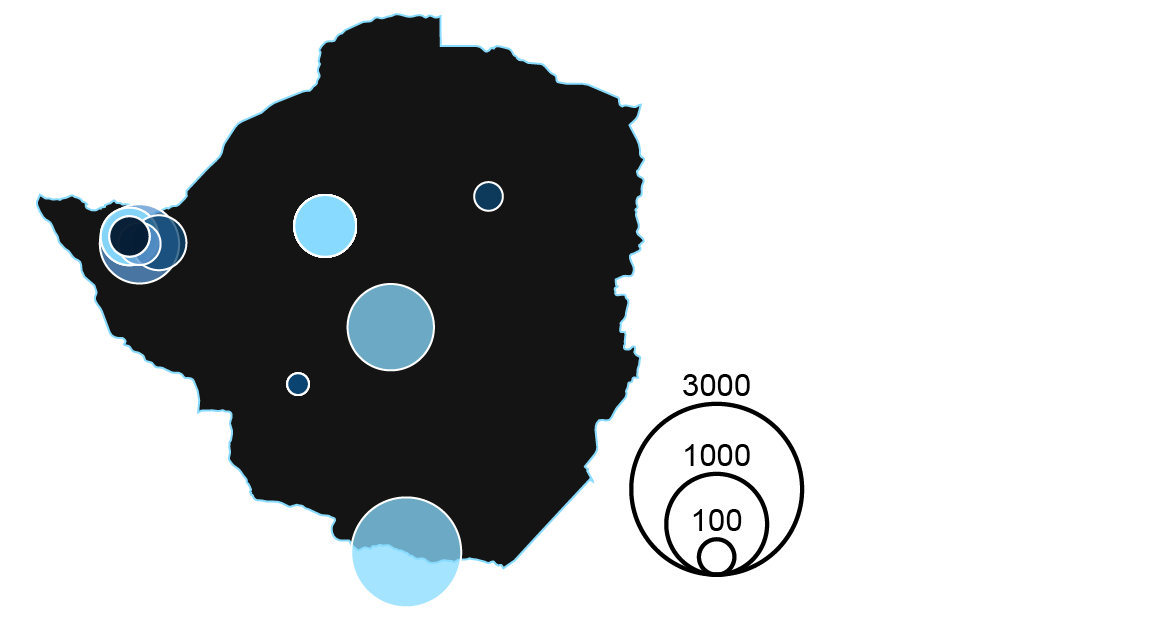

Zimbabwe maintained its position as sub-Saharan Africa’s coal development leader after the first half of 2024, according to the GCPT. The country has 7.4GW of capacity in pre-construction and construction, and has continued to propose new coal projects.

Zimbabwe has more capacity under development than it did a decade ago, and the country has more than tripled its share of the total coal capacity under development globally, ranking fifth as of June 2024.

On the heels of a completed 0.7GW expansion by PowerChina at the Hwange power station in Matabeleland North, Shandong Dingneng New Energy Company announced plans to expand the coal plant by another 0.6GW.

Earlier in the year, Zimbabwean officials reportedly approached China about investments to help with the country’s ongoing electricity shortages. Frequent droughts have diminished the generation capacity of Zimbabwe’s Kariba Dam hydroelectric plant, while a growing industrial sector has boosted demand for power.

The proposed Gweru and Prestige power stations exemplify this rise in energy-intensive industries in Zimbabwe: both projects are captive coal plants slated to supply power to Chinese-backed chrome smelters. Zimbabwe’s government recently instructed the smelters to secure their own power to ease demand on the national grid.

Heavy industries and their captive coal projects have been met with mixed reactions from surrounding communities. According to local reporting, residents of Beitbridge in Matabeleland South are hopeful about the prospect of jobs from the Prestige project. Meanwhile, in Gweru and other parts of the Midlands, community members say Chinese smelter operations have caused the degradation of roads and rural lands, with the community left to foot the bill.

China’s involvement in the captive projects and the new expansion at the Hwange power station are glaring examples of the ambiguity of its 2021 pledge to stop building coal plants overseas.

Similar to the apparent caveat for captive coal, expansion projects associated with existing China-backed projects, such as Hwange, seem to be considered by China as an exception to the moratorium.

Back to top

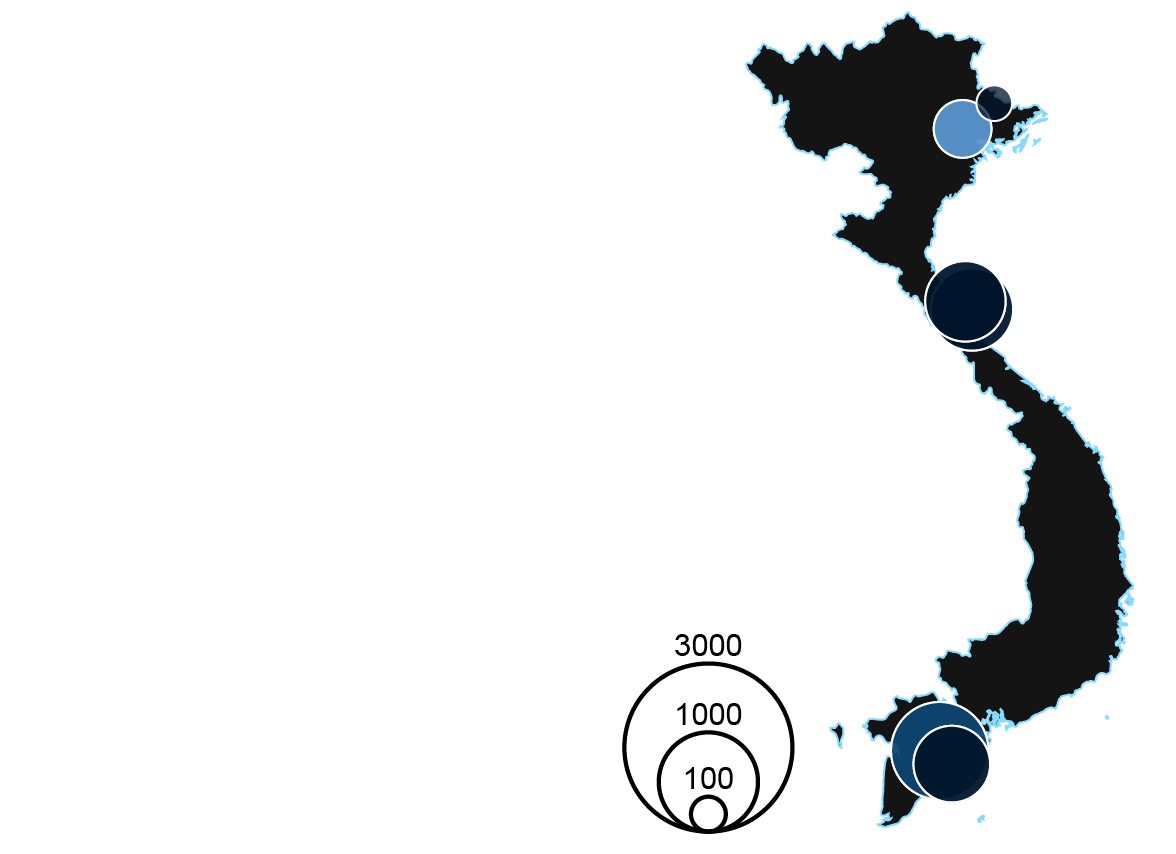

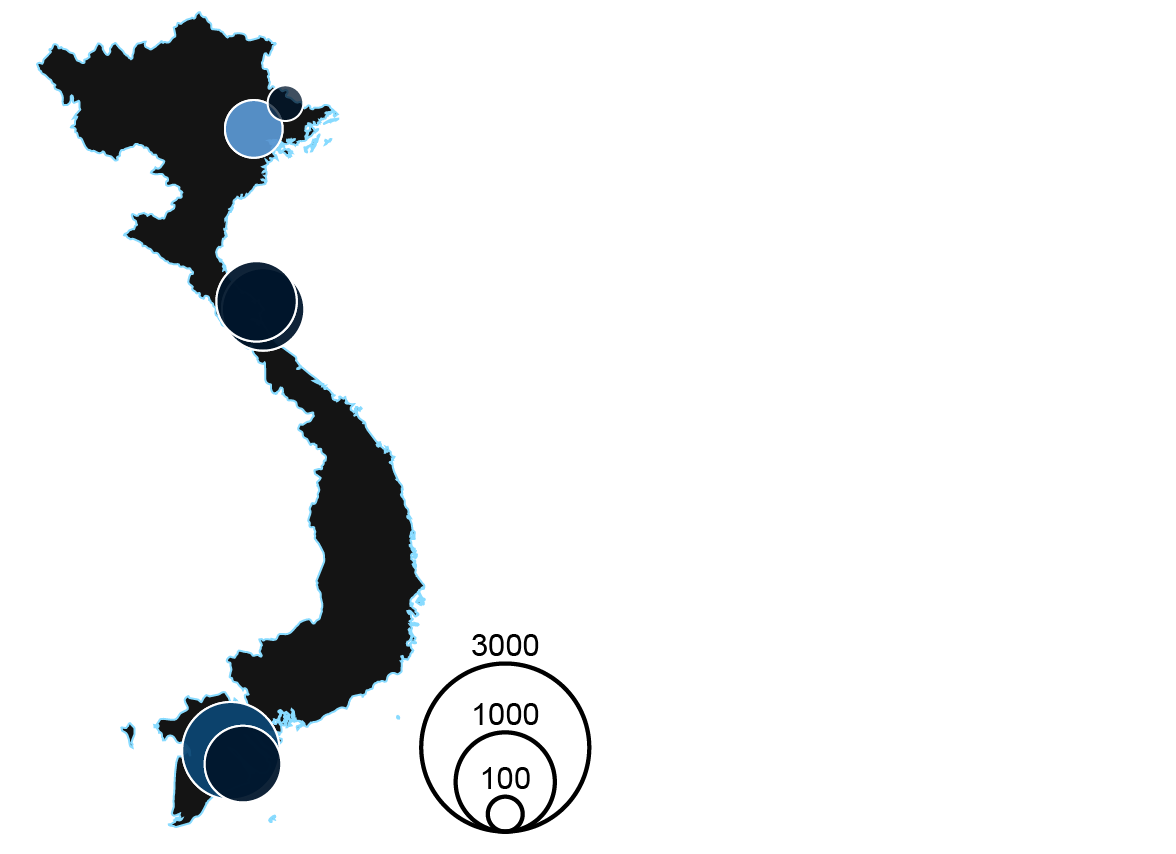

Vietnam

Total planned capacity, GW

According to the GCPT, Vietnam has more than tripled the size of its operating coal fleet in the last decade.

While Vietnam has continued to operationalise and start construction on new coal-fired units in the first half of 2024, its total capacity under development has dropped from 61.3GW in 2014 to 6.7GW today, bringing the country closer to commissioning what could be its last new coal plant.

In that period, more than twice as much capacity has been shelved or cancelled as has been commissioned.

Updated government energy plans have eliminated progressively more planned coal, and the latest version, the power development plan VIII (PDP8), calls for coal to account for just 20% of the country’s electricity mix by 2030. This is down from the 53.2% projected for 2030 in PDP7 and the 34.2% present at PDP8’s release in May 2023.

PDP8 also projects that Vietnam’s coal capacity will peak at 30.1GW, compared to the 27.2GW in operation as of June 2024.

Significant proposed capacity in Vietnam has been stalled for years, apparently unable to make advancements because of a variety of factors. PDP8 says that projects “behind schedule, facing difficulties in changing shareholders and arranging capital”, have until 30 June 2024 to either advance or be terminated.

Some projects, such as Nam Dinh I, have subsequently pivoted to proposing the use of liquified natural gas (LNG) through the first half of 2024.

Another example of a stalled project is Song Hau II, originally proposed about fifteen years ago. It sought to achieve financial close by the mid-2024 deadline, penning a loan agreement with lead arranger Export-Import Bank of Malaysia on 20 June.

However, the financial close was not for the full loan amount needed for the project, and Vietnam’s Ministry of Industry and Trade ultimately terminated the project’s “build-operate-transfer” contract in early July 2024.

The remaining projects under development put Vietnam at risk of breaching the conditions of its JETP agreement, which mirrors the 30GW coal capacity peak established in PDP8.

According to the GCPT, the 4GW already under construction alone would bring Vietnam’s operational coal capacity to 31.3GW, or 1.3GW above the JETP cap, presuming that no units are retired.

Back to top

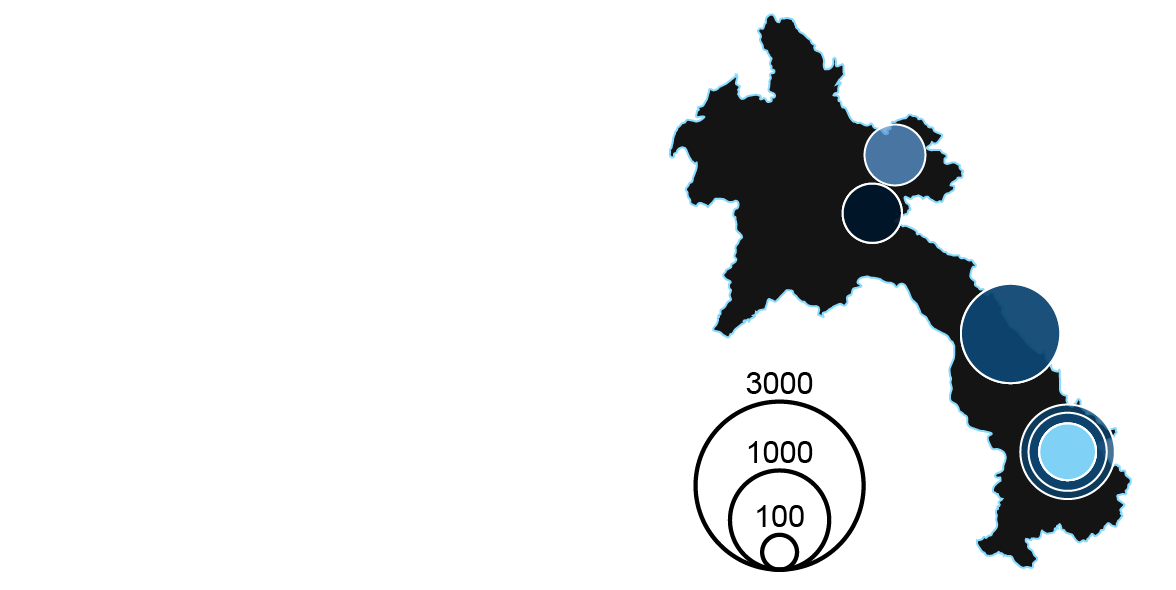

Laos

Total planned capacity, GW

Laos produces the majority of its electricity through hydropower, with over four times more operating hydropower capacity than coal-fired capa no city in mid-2024.

The country is a net-exporter of electricity, but periodic changes in generation between the wet season from May to October and the dry season from November to April result in intervals of energy surplus and energy shortage.

Laos’ renewable energy development strategy, despite largely focusing on the phaseout of fossil fuels, does call for 2.5GW of “mainly” new hydropower and coal capacity to be developed through 2025 to meet growing power demand. The country has 5.4GW of coal capacity under development as of June 2024.

The 0.7GW Nam Phan power station began construction in 2023, the first in-construction coal plant in Laos since 2015, according to the GCPT. Chinese company China Western Power is designing and constructing the power station, and the project is planned to export electricity to neighbouring Vietnam.

The three phase, 1.8GW Phonesack Xekong power station also began preliminary work near the associated Phonesack coal mine in the first half of 2024, with the coal plant expected to be commissioned within three years.

Similar to the Nam Phan project, the Houaphanh power station was planned with a Chinese company and would export electricity to Vietnam, but the proposal has not progressed in several years. Two other proposals in Laos are also stalled, likely due to a lack of funding.

Even if the remaining coal-fired power stations were cancelled, Laos has ongoing plans for domestic coal production and increased coal exports through to at least the end of the decade.

Back to top

Russia

Total planned capacity, GW

Russia has 37.8GW of operating coal power capacity, with coal accounting for 16.6% of total generation in 2023.

In the last decade, the country has retired or transitioned to gas some 7.7GW of coal capacity, while commissioning 2.8GW of new coal capacity, according to the GCPT.

Most coal plants are located in Siberia and the Far East, where Russia’s hydropower plants are also concentrated. The coal plants often respond to the seasonality of hydropower by adjusting their production.

The modernisation of ageing equipment and transition to gas have been overriding themes for Russian thermal coal plants in the last decade.

For example, Khabarovsk-3 is in the process of converting 0.5GW of coal capacity to gas, and the gas-fired Artyomovskaya power station-2 will replace coal units at the Artyomovskaya power station.

Russia is also attempting to expand the gas transportation system for exports to China, in an effort to replace gas exports to the European Union.

As of June 2024, 4.5GW of coal capacity is in planning in Russia and just 0.6GW is under construction. Three proposals, with almost 2GW of combined capacity, appear to be inactive, although they are still listed in recent government planning documents.

In March 2024, two new coal units were announced at the existing Irkutsk-11, to cover the identified power deficit in the Irkutsk region. The proposal appears to be superseding plans for the now-shelved EN+ Mugunsky power station.

At the Partizanskaya power station in the Far East, two units entered construction in 2024 and are slated to supply electricity to Russian Railways, as part of a state project to increase the capacity of the Trans-Siberian Railway.

Back to top

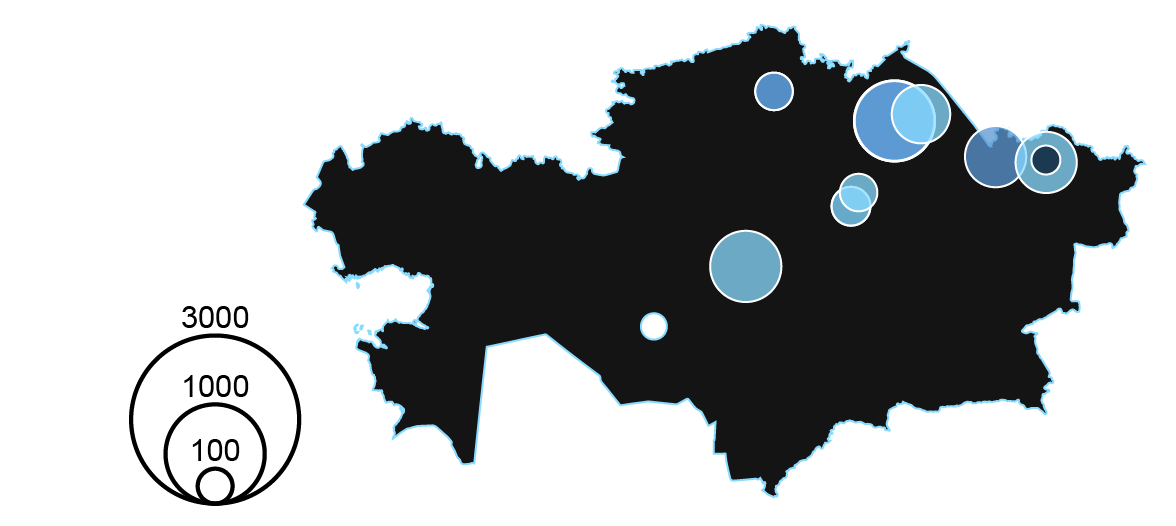

Kazakhstan

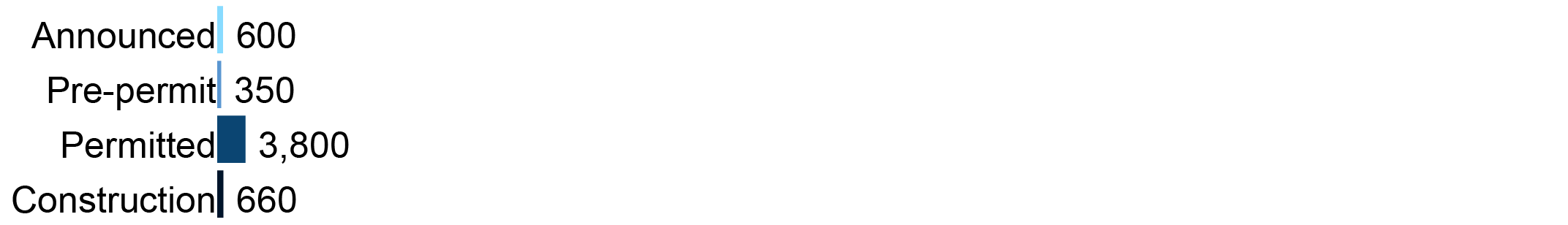

Total planned capacity, GW

Kazakhstan has abundant coal reserves and developed coal infrastructure, with coal fuelling two-thirds of the country’s power generation.

The country is facing growing domestic demand for power and has outdated energy infrastructure, complicating a transition to cleaner fuels.

Worn-out infrastructure in both thermal power stations and the grid have resulted in numerous failures and supply interruptions in recent years. Since many facilities are combined heat and power plants (CHPs), the failures leave residents without heat during the country’s harsh winters.

In early 2024, in response to anticipated power capacity needs and high rates of power equipment depreciation, Kazakhstan’s Ministry of Energy developed an action plan and published an order on power sector development through 2035 that foresees building 26.5GW of new power capacity, including over 4GW of new coal capacity.

The largest proposed coal projects are in Ekibastuz, a major coal mining centre in northeastern Kazakhstan, with 1.3GW of coal capacity planned at Ekibastuz-2 and a 1.3GW greenfield development proposed at Ekibastuz-3.

One of the expansion units at Ekibastuz-2 has been planned for many years, with equipment from China reportedly delivered on site.

However, recent reports have indicated that a Russian company will be contracted to build the expansion, with the Chinese equipment used at Ekibastuz-3 instead.

Although construction was said to be imminent at Ekibastuz-2 in early 2024, it had not yet begun as of June 2024, the GCPT shows.

In late 2023, Kazakhstan also signed agreements with Russian public energy company Inter RAO to build three coal-fired CHPs in north-east Kazakhstan, totalling nearly 1GW of capacity.

Back to top

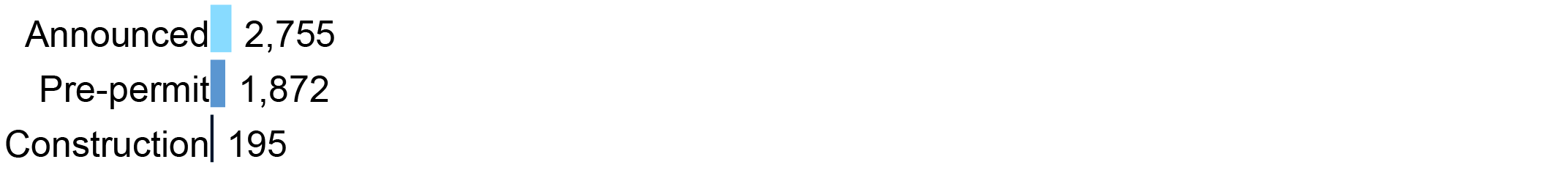

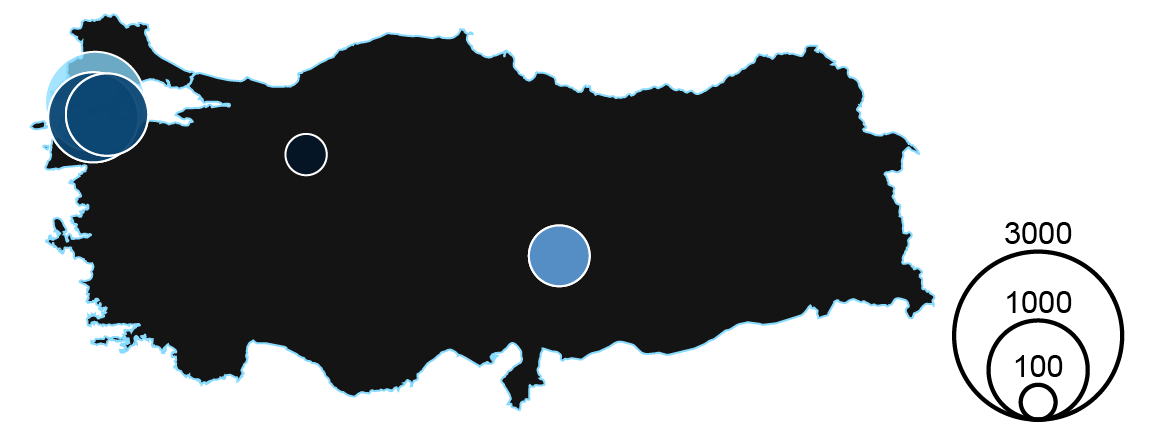

Turkey

Total planned capacity, GW

The 4.8GW of coal capacity remaining under development in Turkey is largely stalled, the GCPT shows.

Most proposed and operating coal plants in the country have faced fierce local resistance in recent years, predominantly surrounding worsening environmental and public health impacts.

Community opposition is also often coupled with legal action, with projects such as the Kirazlıdere power station having multiple open cases filed against the plant simultaneously.

Court decisions have blocked multiple coal plant proposals, including the Alpu and Ilgın power stations, contributing to the 73.8GW of coal capacity that has been cancelled in Turkey since 2014.

Only one of the four pre-construction proposals in Turkey made progress in the first half of 2024, according to the GCPT.

Afsin-Elbistan A, part of the sizable Afşin-Elbistan power station complex in the city of Kahramanmaraş, has a 0.7GW expansion proposal under environmental impact assessment (EIA) review as of June 2024. Residents of the surrounding area impacted by pollution from the existing plant were calling for the Ministry of Environment, Urbanisation and Climate Change to reject the EIA.

Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan had shown support for deforestation in the Akbelen forest in favour of coal mine expansions, but the opening of the land for mining use was reversed in March 2024. Still, following infrastructure damage from the February 2023 earthquake and Erdoğan’s February 2024 call for increased energy independence, Turkey continues to pursue coal development.

The country is continuing to rely on lignite coal rather than replacing the fuel with more cost-effective and clean alternatives.

The country’s 2022 national energy plan projects a 3.2GW rise in coal power capacity from 2025 to 2035.

Back to top

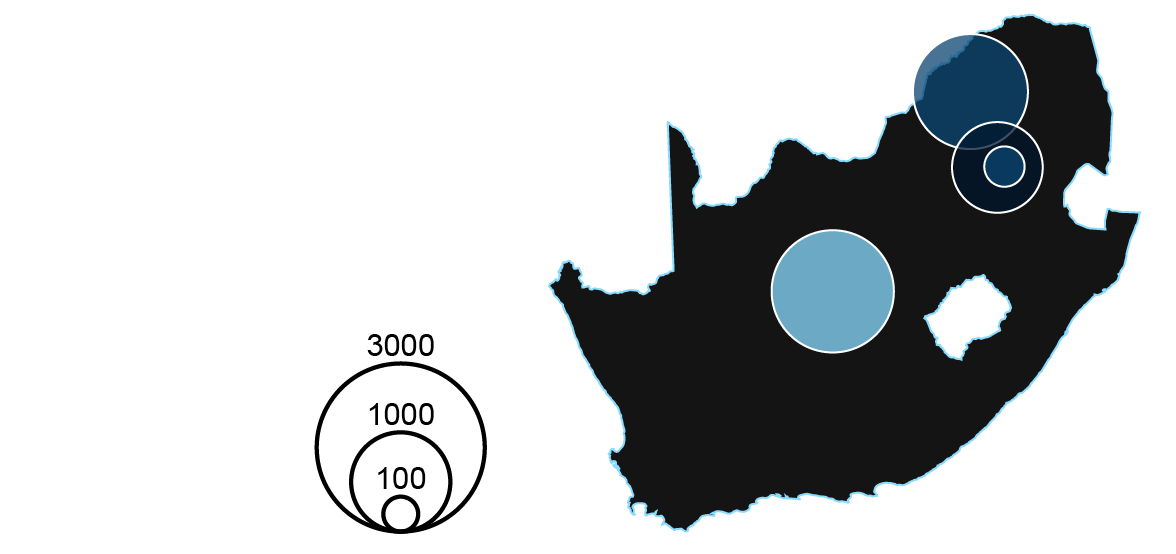

South Africa

Total planned capacity, GW

South Africa runs the world’s sixth largest operating coal fleet, but the country faces an enduring energy crisis that began with rolling blackouts in 2007.

In early 2024, the South African government released an updated draft integrated resource plan that was “inadequate plan to tackle the country’s power supply crisis and its lack of attention to air quality and climate change puts it in conflict with the law and international agreements”, Bloomberg reported, citing the country’s presidential climate commission.

The plan was widely criticised by energy, business and community groups for its reliance on ageing coal power plants and for a lack of ambition on renewable energy.

State-owned utility Eskom has proposed delaying retirements at three coal-fired power plants, a move that could jeopardise South Africa’s $9bn JETP financing.

As of July 2024, however, the government was seeking to renegotiate its JETP deal to extend the life of its existing coal plants. Following South Africa’s mid-2024 election, the country’s newly-appointed minister of forestry, fisheries and the environment stated that South Africa’s just energy transition is “the big issue”, and the newly-appointed minister of electricity and energy promised to be “ultra-aggressive” in renewable energy development.

Still, South Africa ranks second behind Zimbabwe for the most coal capacity under development (3.8GW) in Sub-Saharan Africa.

One of the proposed coal projects, the Chinese-backed Musina-Makhado power station, has an increasingly uncertain future: developers for the Musina-Makhado “special economic zone” were also building a solar plant as of February and in April proposed small modular reactors to supply the area with nuclear power.

Back to top

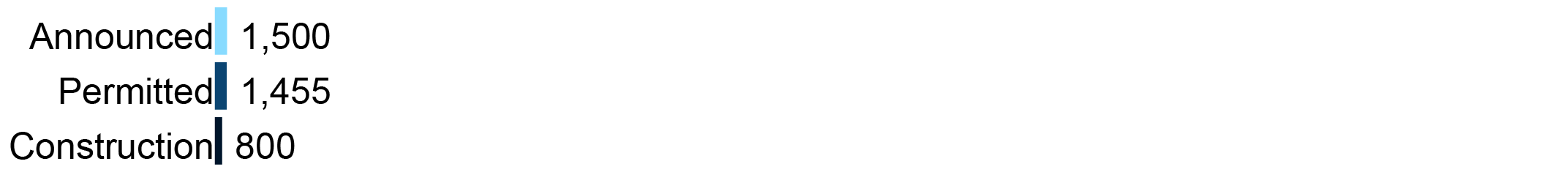

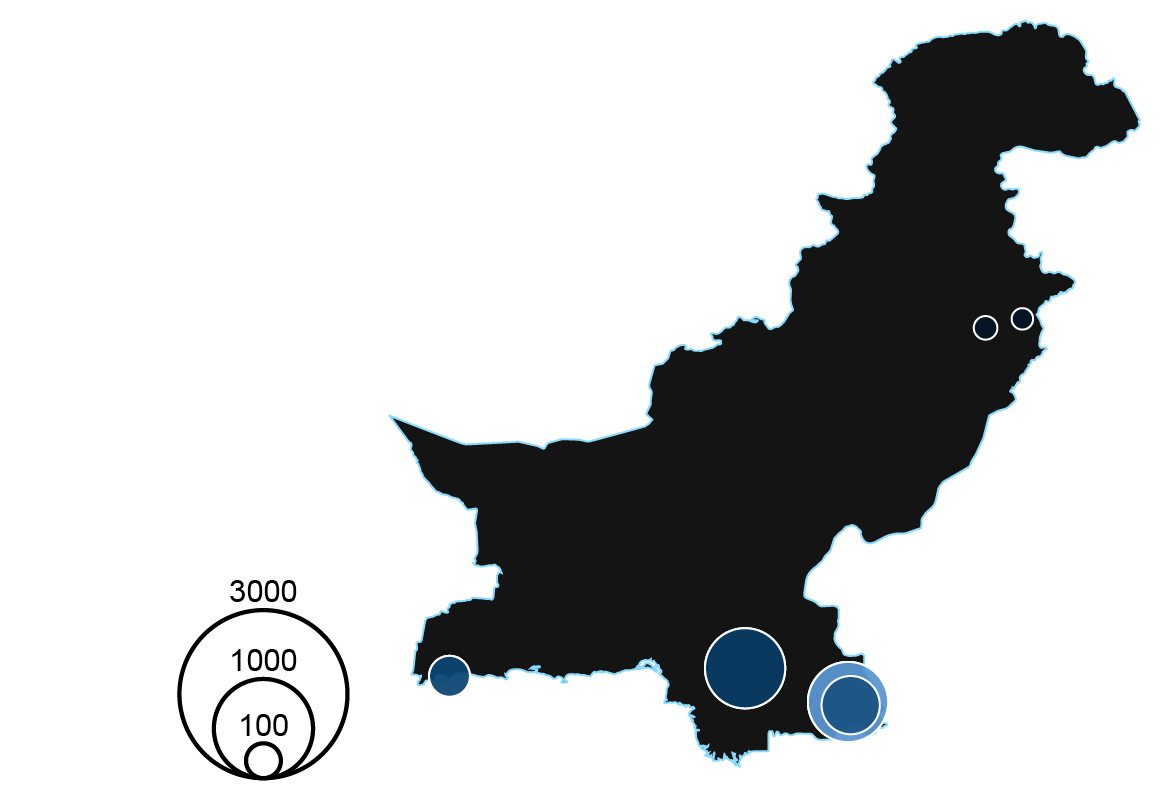

Pakistan

Total planned capacity, GW

Pakistan saw little change to its proposed and operating coal capacity in the first half of 2024, according to the GCPT, yet the coal industry and energy sector were brimming with activity.

The country is still grappling with several confounding problems, including a weak Pakistani rupee, national debt, tariff disputes, costly coal imports and the geopolitical undercurrent of the struggling China-Pakistan economic corridor (CPEC).

In May 2024, Pakistan’s minister of planning promised that the Gwadar power station – a key CPEC project – would have a groundbreaking ceremony by the end of the year. However, in the same month, the project’s Chinese insurer stated that Pakistan owes Chinese companies a combined $1.7bn and that it would not permit additional capital injections into Pakistan’s power sector.

At the Jamshoro power station, the commissioning of a newly-built coal unit stalled due to delays in procuring coal.

In July 2024, a Pakistani delegation visiting Beijing received approval to switch three Chinese-backed power stations from imported coal to domestic Thar coal, a lower-quality lignite that would affect plant efficiencies and may end up undermining Pakistan’s desire for energy independence. While the lignite is mined and used locally, Thar projects are closely tied to foreign companies and global financial markets whose influence could weaken the economic benefits and domestic control that Pakistan seeks.

The proposal follows an agreement with the International Monetary Fund for a $7bn loan program to avoid Pakistan defaulting on existing debts.

Back to top

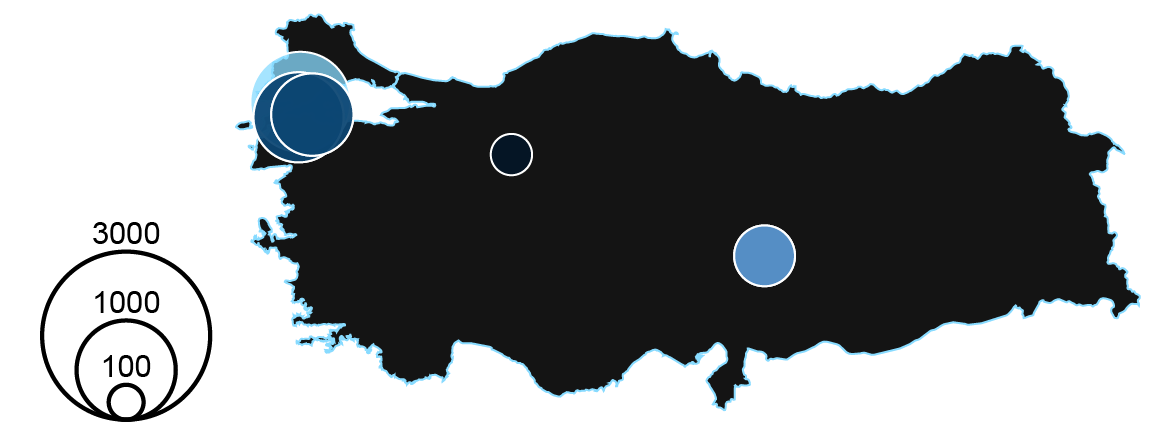

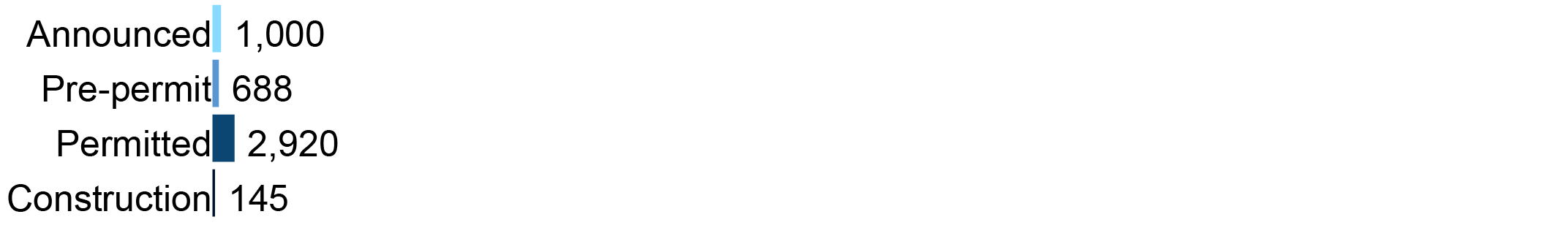

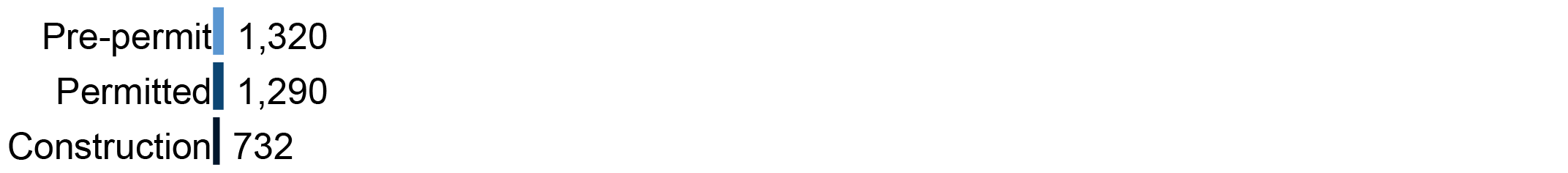

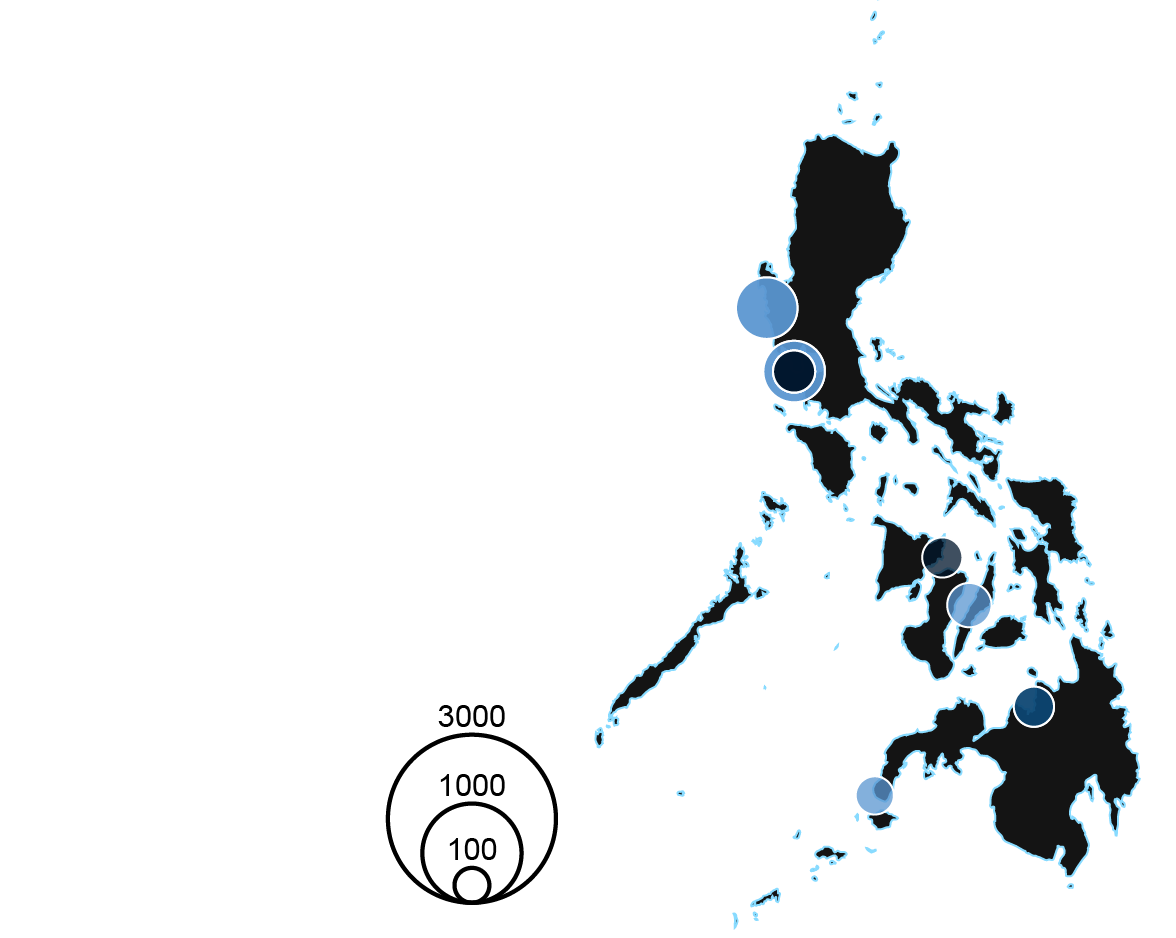

Philippines

Total planned capacity, GW

The Philippines’ moratorium on new coal plant permits, announced in October 2020 following a sustained public opposition campaign to new coal, has generally slowed the development of the country’s proposed coal plants.

However, 2.5GW of coal capacity remains under development as the GCPT shows, and the Philippine government has continued to approve exemptions for coal project proposals in the first half of 2024.

In January 2024, the Philippines’ Department of Energy (DOE) declared that an expansion unit at the Therma Visayas Energy Project would be exempt from the country’s coal plant moratorium, claiming that the unit had already secured its environmental compliance certificate prior to the moratorium’s implementation. In response, climate activists and advocacy groups have called on the DOE to rescind its endorsement of the expansion.

One unit began operating at the two-phase SMC Mariveles power station in March 2024, but coal plant proposals under development in the Philippines have otherwise largely stalled or seen slow progress.

The projects have been deterred by a general dearth of financing and right-of-way issues with transmission lines and infrastructural development – including expansion units at the Masinloc and Calaca power stations, with plans for the latter put on hold by the plant’s owner in May 2024.

Back to top

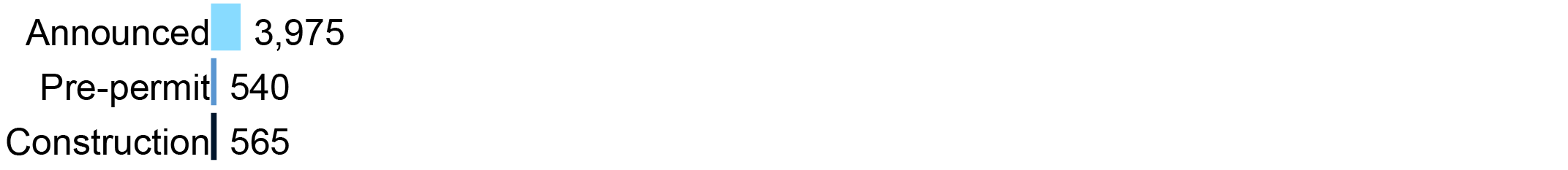

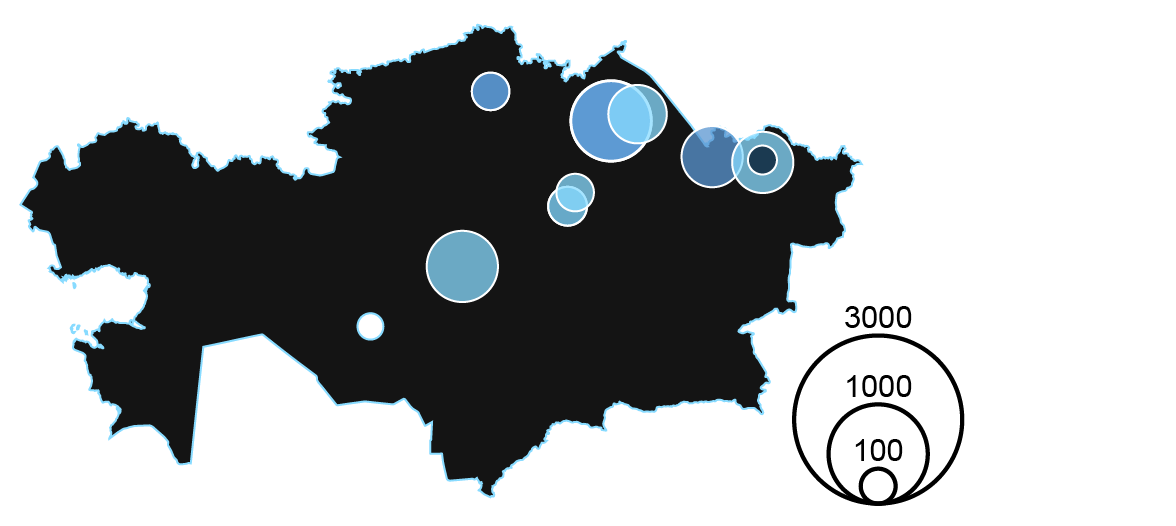

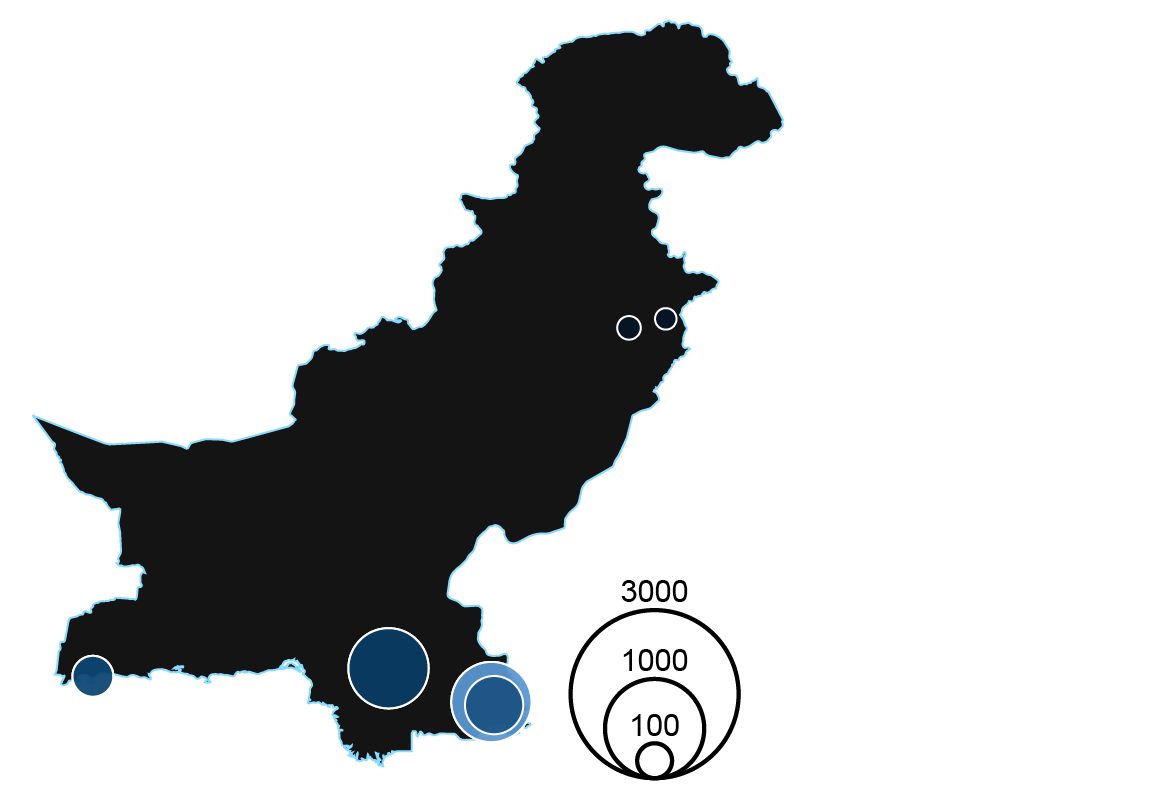

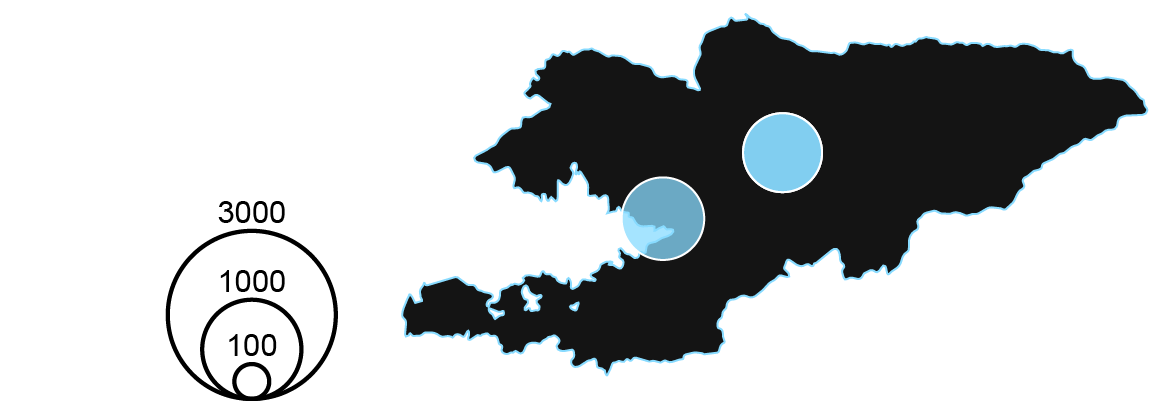

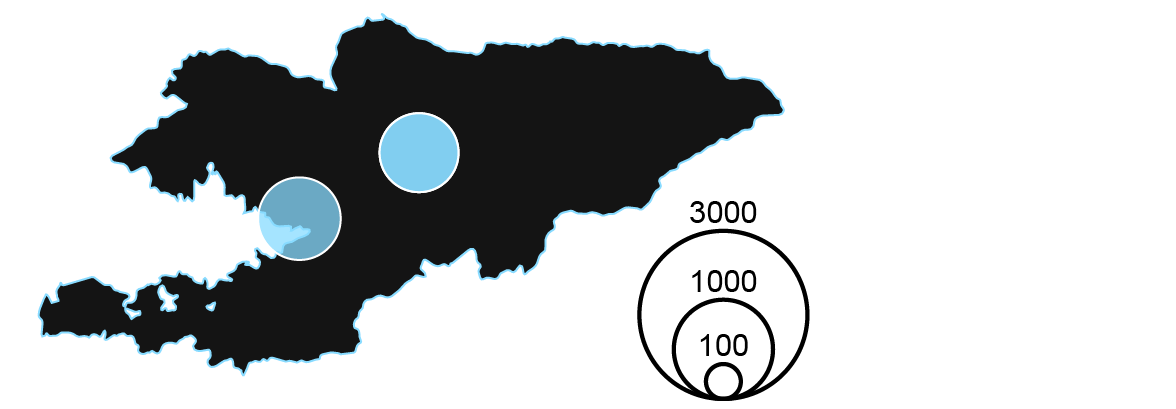

Kyrgyzstan

Total planned capacity, GW

Kyrgyzstan tripled its coal capacity under development from 2022 to 2023 and was one of just eight countries to increase its proposed coal capacity within the 2023 calendar year, the GCPT shows.

As recently as 2021, Kyrgyzstan had no active coal plant proposals under development. In early 2022, however, plans for the 0.6-1.2GW Kara-Keche power station – which had been in planning from 2014 to 2016 – was revived.

In January 2024, the Ministry of Energy and China National Electric Engineering signed a memorandum for the construction of a 0.6GW coal unit in Kara-Keche, as well as several hydropower plants.

In late 2023, the 0.7GW coal-fired Jalal-Abad power station was announced to be built by a Russian contractor. Coal production was also to be expanded in the country, with plans to exploit the Kara-Tyt coal deposit established at the 2023 Kyrgyz-Russian interregional conference.

Back to top

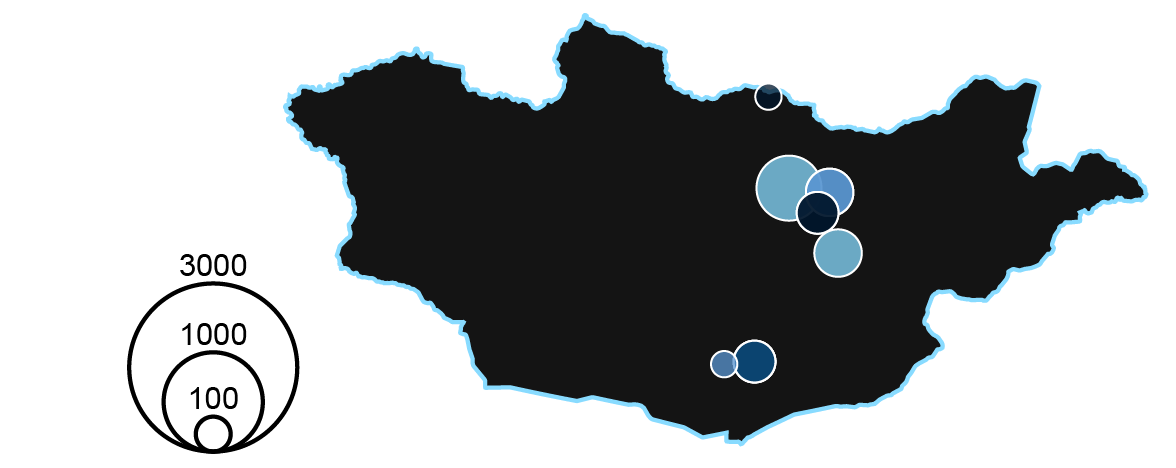

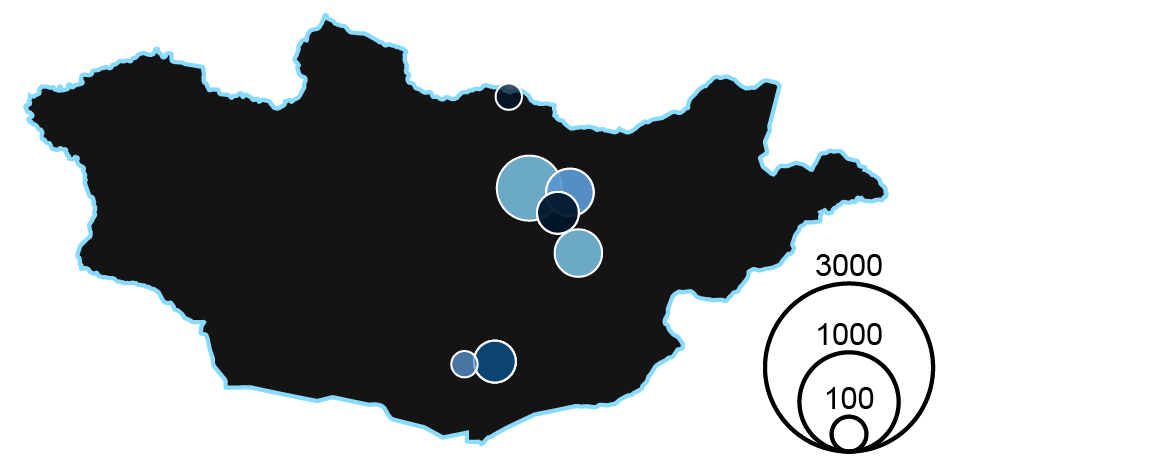

Mongolia

Total planned capacity, GW

Mongolia’s coal capacity under development sits at 1.9GW, according to the GCPT.

This capacity slowly declined from a high of 8.1GW in 2014 and then sharply fell in 2023, with the shelving of 5.3GW at the Shivee Ovoo power station, a long-proposed mega project that has never found sufficient support.

As of March 2024, the long-awaited Tavan Tolgoi power station which is set to supply power for domestic mining operations, remained in limbo without a contractor – after a failed tender process in 2023.

Other projects advanced in the country, with the small CHP Sükhbaatar power station beginning construction and the expansion of Dornod power station starting operation.

Back to top

The designations employed and the presentation of the material on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of Carbon Brief concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries.

Sharelines from this story