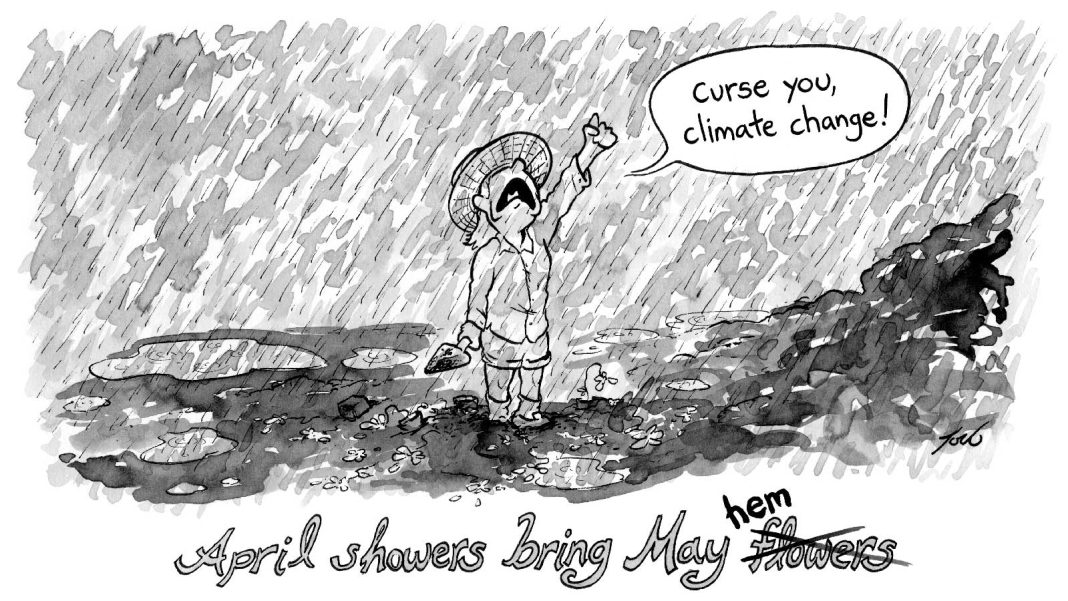

When it rains, it pours.

Today’s rainstorms give new meaning to this age-old expression.

The United Kingdom has gotten wetter over the last few decades, though annual totals varied widely, according to the State of the UK Climate 2022 report. Despite getting 6% less rain than average in 2022, the longer-term picture shows a slight increase in heavy rainfall across the UK. The most recent decade studied (2013–2022) was 8% wetter than 1961-1990. Winters were especially wetter this past decade — 10% over 1991-2020 and 25% over 1961-1990.

So far, six of the 10 wettest years on record took place after 1998, according to analysis from the Met Office. And the last decade also saw higher total rainfall and more rainfall events surpassing 50 mm. Together, these numbers point to an uptick in rainfall frequency and intensity across the country.

“The UK’s highly variable weather means that every year is different”, wrote Met Office Senior Scientist Mike Kendon in a Met blog. “However, there are clearly some common themes: firstly, our climate is continuing to change dramatically – 2023 has been … wetter than average — and we expect this to continue in future decades. Secondly, we have broken a number of high temperature and rainfall records over the year, and this pattern is also consistent with our changing climate”.

Some recent heavy rain events stand out as particularly destructive. South Yorkshire endured historic flooding in the autumn of 2019, now its wettest season on record. On 7 November some locations saw as much as 82.2 mm of rainfall in a single day — over a month’s worth of typical rainfall. Then on 25 October, some places counted 24-hour totals of nearly 50 mm. Severe impacts included two rivers flooding, leading to one fatality. More than 500 properties flooded, 1200 households were evacuated, and insurance loss estimates reached up to £120 million.

And Eastern Scotland had its wettest October on record in 2023. Storm Babet brought historic flood damage to areas like Angus County, where 60 people were rescued by boat, and 19 October became the rainiest day on record in a series from 1891 — by a wide margin.

What causes heavier rainfall?

Climate scientists attribute increasingly extreme precipitation events to warmer air and its ability to “hold” more water vapour than cooler air. In the UK, average temperatures are rising, with the most recent decade (2012 to 2021) proving an average 1°C warmer than the 1961 to 1990 average.

Higher temperatures cause more liquid water to evaporate from soils, plants, oceans, and waterways, becoming water vapour. This additional water vapour means there’s more moisture available to condense into raindrops when conditions are right for precipitation to form. And more moisture spells heavier rain, or heavier snow during winter.

How much water moves into the atmosphere when it’s hot out? The Clausius-Clapeyron equation, which relates temperature to the behaviour of water vapour molecules, dictates that for every 1 degree Celsius of warming, water vapour can increase by about 7%.

What are the consequences of heavy rainfall?

Under normal circumstances, more rain would generally be considered a blessing, especially for drinking water and agriculture. Excessive rainfall, however — specifically the fast rates at which it falls and the overwhelming accumulations it drops — does more harm than good.

As rain falls at rates too fast for soil to absorb, rainwater doesn’t have enough time to soak into the ground. This water, known as stormwater runoff, instead collects and flows through gardens, roadways, and over other surfaces, increasing the risk of floods and soil erosion. Localised flooding can close roads, disrupt mass transit, and damage infrastructure. For example, between January 2020 and December 2022, councils received 740 claims from property owners related to flash flooding, ultimately paying out more than £975,000.

As the stormwater rushes toward low-lying areas, it picks up sediments, chemicals, heavy metals, rubbish, and debris. Eventually, the stormwater drains through outfalls and soakaways and is discharged into nearby rivers and streams. This process degrades water quality, both for human use and in ecosystems.

What’s more, like many nations, much of the UK’s critical water infrastructure, including dams, levees, sewers, and wastewater treatment systems, is ageing, which could increase the risk of failure from extreme precipitation events. A report by Water UK, a trade association for the water industry, projects that 350,000 km of water mains and 625,000 km of sewers in the UK are likely to fail more often, interrupting supply by more than 25% until ageing assets are replaced. The UK government reported in late 2023 that it is actively addressing this issue by increasing storm overflow monitoring and investing £56 billion into infrastructure improvements.

Overall, the official projection is that winters in the UK will generally continue to get wetter, while summers get drier — and when summer rain does fall, it will likely become more intense over time, increasing surface water flooding impacts. Looking further ahead, a study in the journal Nature Communications suggests that under a high greenhouse gas emissions scenario, extreme rainfall could be four times more common and erratic by 2080 compared to the 1980s.

What you can do to protect yourself from floods

According to the National Infrastructure Commission, up to 600,000 properties could be at high risk of surface water flooding over the next three decades, and already nearly 1 million homes in the UK have more than a 1% chance of flooding in any given year.

Although you may not be able to stop downpours, you can reduce the impacts of heavy precipitation by taking these steps:

- Understand your risk at a local level. What is the long-term risk of flooding in your area? What are the possible causes of flooding there? Knowing these facts allows you to anticipate your individual flood risk before heavy rain arrives in the forecast. Visit the following government pages to check the long-term flood risk for homes in England, Scotland, Wales, or Northern Ireland.

- Purchase flood insurance. Homeowners can look for insurance advice from the National Flood Forum or MoneyHelper. If you’re in a flood-risk area, check whether your home is eligible for lower-cost flood insurance through Flood Re.

- Plant a rain garden. Rain gardens — shallow, bowl-shaped garden beds — help capture and filter stormwater runoff by giving rainwater a place to pool and slowly seep into the ground. Slowing down the flow of stormwater limits the pollutants, such as fertiliser, motor oil, and pet and garden waste, that are washed from your garden into storm drains and ultimately into waterways.

- Stay safe during and after a flood. Always follow advice from the emergency services, and if you have to stay in a flooded property, move as far upstairs as possible. Never walk or drive through floodwaters. It only takes six inches of fast-moving water to sweep a 4×4 vehicle off the road, says the National Flood Forum.

One takeaway: Small but mighty acts like those outlined above will prove increasingly essential to help hold back the downpour-caused deluges.

This article was adapted and updated for UK readers by Daisy Simmons in 2024. Read the original by Tiffany Means.

We help millions of people understand climate change and what to do about it. Help us reach even more people like you.