By Christopher Monckton of Brenchley

Some time ago, I sent Professor Richard Lindzen an estimate of how much warming a straight-line progress to net zero emissions by all nations on Earth would achieve. He was intrigued. Now – with the stellar team of Professors Happer and van Wiijngaarden – he has prepared a short paper, now published by our friends at the CO2 Coalition, that offers a scientific answer to that question:

By chance, on receiving news of the new paper, I was putting the finishing touches for a paper by my own team that covers the same subject matter. Our paper is intended for publication in an economics journal, where, like all papers presenting a serious and scientifically credible challenge to the official catastrophe narrative, it will probably be rejected out of hand, not because it is wrong but because it is right.

This article will briefly describe the two methodologies for answering the question “How much warming would net zero by 2050 prevent?”

Both approaches start by assuming that all nations (not just the West, against which the international climate accords are selectively targeted) move linearly together from their current emissions to net zero, achieving it by 2050.

First, here is the abstract from the professors’ paper –

Net Zero Averted Temperature Increase

Using feedback-free estimates of the warming by increased atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) and observed rates of increase, we estimate that if the United States (U.S.) eliminated net CO2 emissions by the year 2050, this would avert a warming of 0.0084 C (0.015 F), which is below our ability to accurately measure. If the entire world forced net zero CO2 emissions by the year 2050, a warming of only 0.070 C (0.13 F) would be averted. If one assumes that the warming is a factor of 4 larger because of positive feedbacks, as asserted by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the warming averted by a net zero U.S. policy would still be very small, 0.034 C (0.061 F). For worldwide net zero emissions by 2050 and the 4-times larger IPCC climate sensitivity, the averted warming would be 0.28 C (0.50 F).

The professors start by assuming that direct warming by an anthropogenic forcing equivalent to doubling the CO2 in the air compared with 1850, before adding any feedback response, will be about 0.75 C, while IPCC’s midrange final warming, after adding feedback response, is four times greater, at 3 C.

The professors take today’s CO2 concentration as 427 ppmv, which, on current trends, would rise by 64 ppmv to 491 ppmv by 2050, the official target date for net zero. Since the CO2 forcing is an approximately logarithmic function of concentration, the direct warming from now to 2050 on business as usual would be 1 C x log2(491 / 427), or about 0.15 C.

They then estimate that one-eighth of the 64 ppmv increase in concentration from now to 2050 – i.e., 8 ppmv, of which about half, or 4 ppmv, would be abated if the US alone attained net zero by 2050, reducing the 491 ppmv otherwise-projected CO2 concentration in 2050 to 487 ppmv.

Then, if the rest of the world went on emitting as at present, the economic sacrifice of the U.S. in alone attaining net zero would reduce the 0.15 C warming by 2050 by just 0.01 C to 0.14 C. Even if one assumed, as IPCC does, that feedback response would triple or quadruple the 0.75 C direct warming by doubled CO2, U.S. net zero would decrease global temperature by only 1/30th C by 2050, while global net zero would reduce it by little more than 1/4 C.

Our own approach is even simpler than that of the professors. First, here is our abstract –

Has interdisciplinary incomprehension vitiated economic-assessment models?

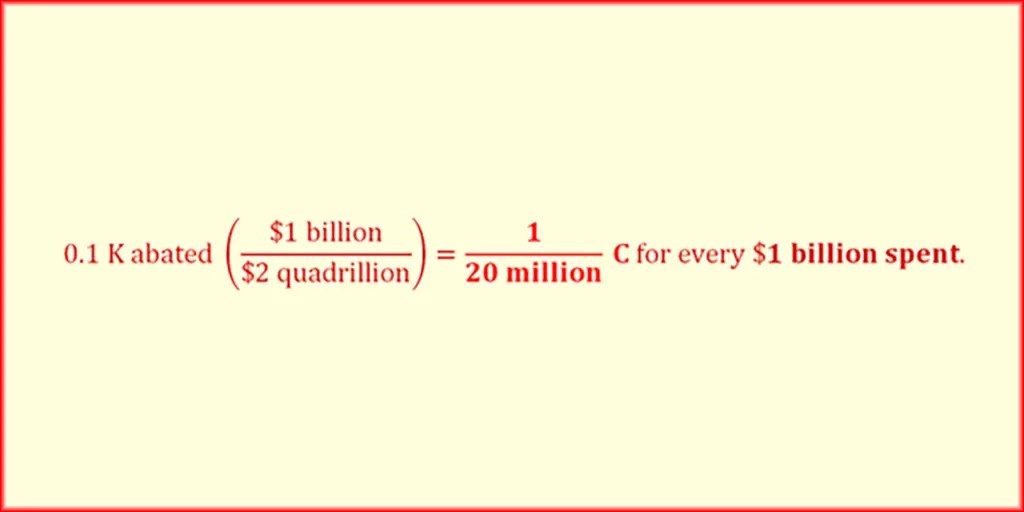

Integrated-assessment models that study the economic effects of abating global warming are of their essence interdisciplinary. At minimum, they demand knowledge of optical physics (to study the influence of anthropogenic forcing on climate); climate sensitivity (the “how much warming” question); probability theory (to assess data uncertainties); mitigation economics (for benefit-cost analysis); geology (are specialist mineral resources sufficient for global net zero energy infrastructure?); engineering (control theory, wind and solar systems and electric vehicles); and geopolitics (climate accords target the West, whose energy prices thus exceed by an order of magnitude those in the East, where emissions are rising fast). It is here shown that climate sensitivity is overstated by double; that, notwithstanding trillions spent on abatement since 1990, the uptrend in forcing remains linear; that even if all nations attained net zero by 2050 only 0.1-0.2 C warming would be abated by then; that the cost would be $2 quadrillion; that each $1 billion spent would abate one 20-millionth C warming by 2050; that in most Western grids installed wind and solar nameplate capacity exceeds mean hourly demand; that further installations would cost much but abate nothing; that the mass of electric-vehicle batteries increases energy consumption per kilometer by 25-100%; that insufficient techno-metals exist for even one 15-year generation of net-zero infrastructure; and that the West sets itself at a strategic terms-of-trade disadvantage in relying upon integrated-assessment models so vitiated by interdisciplinary divides that they do not reflect such readily-established facts as these.

Our results broadly agree with those of the professors, though we take an even simpler route. First, we assume that direct warming by doubled CO2 is 1 K, the average of four published results. We conclude, in line with the professors, that only 0.1-0.2 C warming would be abated by 2050 even if the whole world moved linearly from current emissions to net zero by then.

Therefore, the United States’ contribution, on its own, would be 1/40th to 1/80th C. Indeed, the whole of the West would abate only 1/30th C, while the UK, on its own, would abate only 1/1000 C by 2050 even if it attained net zero by 2050, which it will not.

Step 1: The trend in anthropogenic greenhouse-gas forcing

Our method begins with this devastating graph of NOAA’s Annual Greenhouse-Gas Index. We start here because, unlike the professors’ analysis, our analysis takes account of all anthropogenic greenhouse-gas forcing, not just that from CO2:

All those trillions spent – in the West almost alone – on attempted emissions abatement have had no discernible effect whatsoever on the near-perfectly linear growth rate of anthropogenic forcing over the past one-third of a century since IPCC’s first report in 1990.

Note in passing that the growth in methane concentration has been minuscule, altogether removing cow-farts as a legitimate pretext for the Left’s intended destruction of yet another Western industry – this time the beef and dairy industry.

Step 2: The expected increase in anthropogenic forcing, 2023-2049

Even if all global warming is anthropogenic (which it may not be), on business as usual the near-linear 1 W m–2 uptrend of the past three decades in CO2-equivalent radiative forcing (NOAA op. cit.) may be expected to continue at 1/30th W m–2 yr–1 over the next three decades. Therefore, if all nations moved stepwise together towards net zero emissions by 2050, half the next 0.9 W m–2 of forcing, or 0.45 W m–2, might in theory be abated.

Step 3: From forcing abated to medium-term warming abated

IPCC (2021, p. 7-7) yields the effective doubled-CO2-equivalent radiative forcing as 3.93 W m–2 at midrange. Nijsse (2020) gives the consequent doubled-CO2 sensitivity over the 21st century as 1.68 K. Warming per unit of forcing is thus 1.68 / 3.93, or 0.43 K W–1 m2, so that global net zero would abate 0.45 x 0.43, or just 1/5 K.

The more detailed appraisal that follows will show that first-order estimate to be optimistic.

Step 4: The rate of global warming is half the predicted midrange

When the global climatological community issued its first collective prediction of the rate of global warming (IPCC, 1990), four emissions scenarios A-D were presented. Scenario A represented business as usual.

Predicted Scenario-B growth in anthropogenic forcing from 1990-2025 (ibid., p. 56, fig. 2.4B) was near-coincident with such growth where annual emissions were fixed at 1990 levels (ibid., p. 338, fig. A.15).

However, since 1990 annual emissions have risen near-linearly by more than 75%, from 32.5 Gte CO2e in 1990 to 57.2 Gte CO2e in 2022 (UNEP 2023).

Outturn, then, tracks Scenario A, by which 21st-century global mean surface temperature would rise by 0.3 [0.2 to 0.5] C decade–1, or 3 [2 to 5] C century–1, or 3 [2 to 5] C equilibrium doubled-CO2 sensitivity (ECS).

IPCC (2021) projected equilibrium doubled-CO2 sensitivity of 3 [2 to 5] C. However, observed warming from 1990-2023 (UAH 2023) was only 0.15 C decade–1, implying that – not least owing to the control-theoretic error – the long-standing midrange global-warming predictions are overstated by a factor 2.

A third of a century after the global scientific community first came together to assess the anthropogenic influence on climate, observed decadal warming has proven to be half the midrange that was originally (and still is) predicted. What is more, the trend shows little sign of acceleration in almost half a century.

Step 5: Global warming abated by worldwide net zero

Combining these midrange initial conditions, the otherwise-expected global warming that would be abated if all nations were to move directly towards net zero, reaching the target by 2050, would be less than 1/10th C (Table 1).

Step 5: Global warming abated by Paris-obligated net zero

Since the chiefly Western Paris-obligated nations, responsible for only 30% of new emissions, are in practice the only nations taking substantial steps towards net zero, even if the Paris-exempt nations were to cease increasing their emissions the global warming abated by 2050 would be less than 1/30th C.

Step 6: Global warming abated by single-nation net zero

The contribution of any individual Western nation to net zero would be negligible. For instance, if the United States, accounting 12% of global emissions, were to attain net zero, its contribution to abatement of global warming by that year would be ònly 1/100th C. The United Kingdom, with just 0.8% of global emissions, would abate less than 1/1000th C.

Step 7: The cost of attaining net zero

Our analysis goes a little further than that of the Professors. We look at the global cost of attaining net zero emissions. We begin with one of the few genuine cost figures available, since there has been a concerted effort to conceal the true cost from the public.

The global cost of attaining net zero, extrapolated pro rata from the estimated $3.8 trillion cost of net-zeroing the UK power grid, which accounts for just 25% of all UK emissions, which in turn represent only 0.8% of all global emissions, might reach $2 quadrillion:

Step 8: Value for money

Each $1 billion spent might prevent only one 20-millionth of a degree of global warming by 2050. Even if value for money were ten times better than that (which it is not), expenditure on emissions abatement would have no rational justification:

Let the professors’ conclusion be ours also:

“There appears to be no credible scenario where driving U.S. emissions of CO2 to net zero by the year 2050 would avert a temperature increase of more than a few hundredths of a degree centigrade. The immense costs and sacrifices involved would lead to a reduction in warming approximately equal to the measurement uncertainty. It would be hard to find a better example of a policy of all pain and no gain.”

Related