New data reveals a rebound in Chinese financing of renewable energy projects in Africa in 2023, following a lull over the past few years.

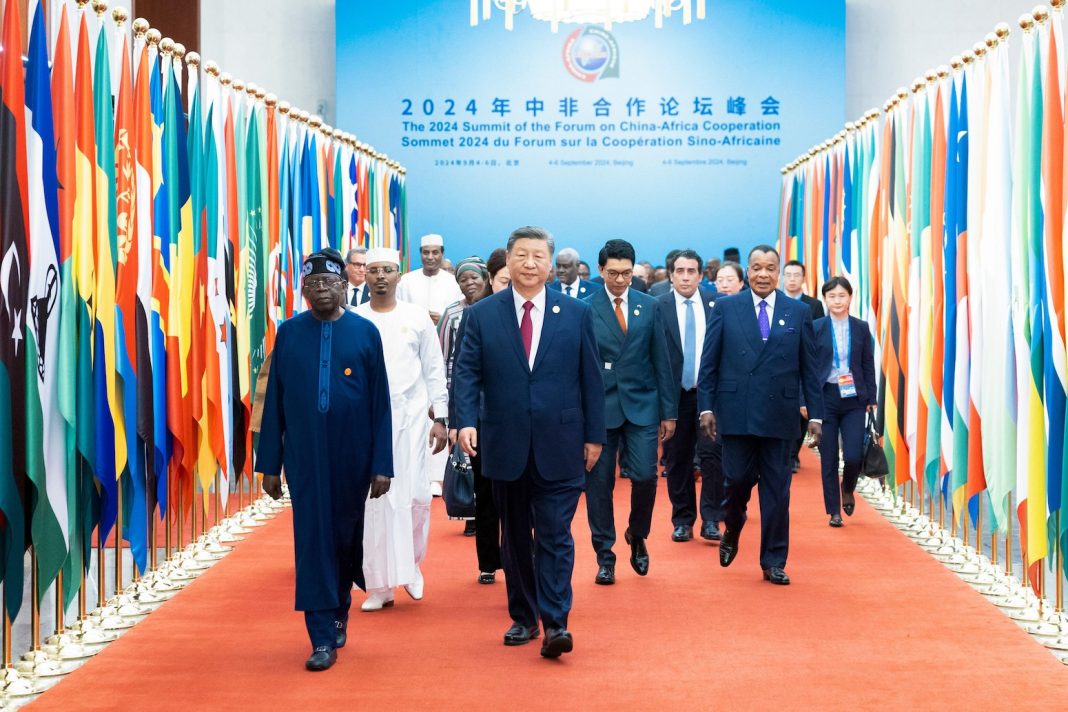

Climate cooperation between China and Africa was a key focus of the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC), which concluded on 6 September, when dozens of leaders gathered in Beijing for the three-yearly meeting.

A landmark declaration was issued at the previous FOCAC, held in 2021, that “positioned climate cooperation as an important pillar” of future cooperation. The same year, the Chinese government declared that it would stop funding coal power.

A pause in policy bank loans for energy projects had raised concerns around the future of Chinese energy lending in Africa. However, the new data indicates that the pause signified a reset, as banks adjusted to requirements to fund low-carbon energy and “small and beautiful” projects, according to the Boston University Global Development Policy Center.

This article examines the shift, and explores the challenges for Chinese financing of the future buildout of renewable energy on the continent.

‘Established’ interests

China has been a significant financier of energy projects in Africa, especially of fossil fuel projects. Some 75% of the continent’s electricity comes from fossil fuels, although it accounts for less than 3% of the world’s energy-related carbon dioxide emissions and has the lowest electrification rate of all inhabited continents.

In the past, the bulk of Chinese financing had been driven by the backing of China’s two policy banks – the Export-Import Bank of China (EXIM) and the China Development Bank (CDB) – and directed particularly towards coal-fired power plants.

The two banks had issued $182bn in loans across Africa, primarily into the energy sector. According to the Boston University Global Development Policy Center, between 2000 and 2023, 15% of the policy banks’ total loans by value went to fossil fuels and 12% to hydropower plants.

By contrast, less than 1% of loans by value were issued for solar, wind or geothermal projects.

This is largely due to the established networks between China’s state funders and state-owned enterprises (SOEs). Historically, most SOEs have focused on conventional power, such as coal and hydropower, according to the China-Global South Project.

Dr Frangton Chiyemura, lecturer in international development education at the Open University, tells Carbon Brief that China’s international development activity in the 2000s and 2010s reflected the country’s own “internal development trajectories” at the time, as China had also developed a coal-dominated power system that featured hydropower as the largest low-carbon source.

The majority of energy project developers, mainly SOEs, in Africa during this “going out” period held expertise in hydropower and coal, leading to a greater number of these projects being financed and built, he says.

He adds that these SOEs “had state backing, in terms of insurance, finance and access to respective African governments…[and] did not do much of the groundwork of trying to establish markets”.

‘Small and beautiful’

In 2023, EXIM and CBD committed $502m to three energy projects, including a solar plant in Burkina Faso and a hydropower plant in Madagascar, ending a “hiatus” on energy loans in 2021 and 2022, shown in the figure below.

The two-year lull in the Chinese policy banks’ energy lending in Africa may have been driven in part by economic pressures during the COVID-19 pandemic.

However, it also seems that the banks paused to make “the necessary adjustments” to their investment strategies following pledges in 2021 by Chinese president Xi Jinping to stop funding coal power and shifting to build “small and beautiful” projects, the Boston University Global Development Policy Center says.

The 2021 FOCAC climate change declaration also affirmed that “China will further increase investment in Africa” on renewable energy and other low-carbon projects, and “will not build new coal-fired power projects abroad”.

The two-year dearth of loans was not “unique” to Chinese policy banks, Chiyemura tells Carbon Brief, adding that loan disbursements to Africa from western nations also fell during the pandemic period.

He also agrees that the shift was accelerated by Chinese lenders switching their focus from “quantity” to “quality”, with greater consideration of the investment risks and societal impacts associated with new projects.

During this period, other Chinese stakeholders, ranging from SOEs such as PowerChina and China Three Gorges Corporation to privately held companies such as JA Solar, agreed to finance or participate in renewable energy projects.

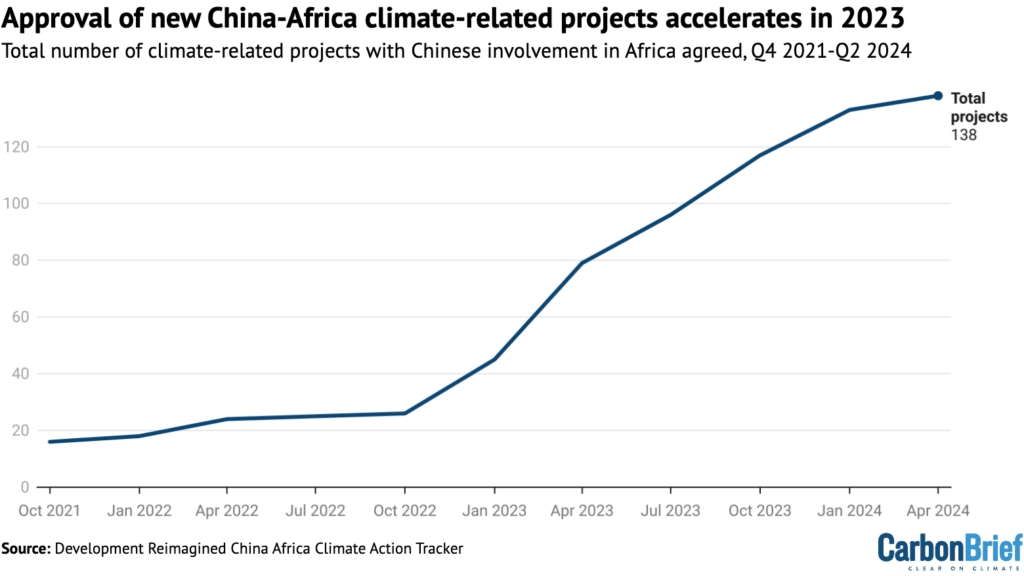

According to separate data compiled by consulting firm Development Reimagined and shown in the chart below, 138 new climate-related projects have been agreed since the 2021 FOCAC – and the number has accelerated over the past 18 months.

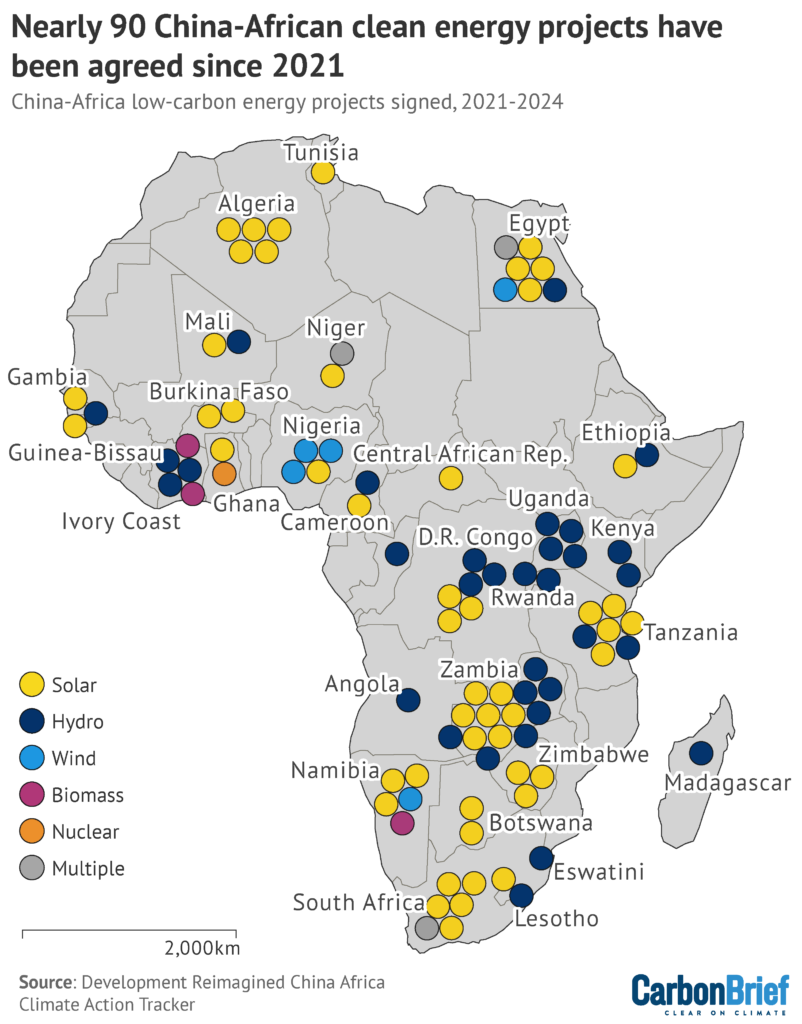

The projects logged in the database include more than 20 gigawatts (GW) of solar projects, 9GW of hydropower as well as 1GW of wind power projects, all shown in the map below.

These were funded by a range of sources, including Chinese and non-Chinese companies, African and other non-Chinese financial institutions, and multilateral development banks.

The consulting firm’s program manager and policy lead on China’s climate finance, Fu Yike, tells Carbon Brief that Chinese SOEs have expressed interest in “exploring new ways to do projects in Africa” following Xi’s 2021 pledges, including through involvement in solar projects.

SOEs were involved in 46 and 5 respectively of 55 solar and wind projects listed in the database.

According to Development Reimagined’s analysis, China could install more than 224GW of clean energy in Africa by 2030, meaning its participation in Africa’s energy transition will be crucial for the continent to meet its target of 300GW by 2030.

Fu adds that solar installations, in particular, are expected to be a feature of China’s energy installations in Africa in the future.

Steep ‘learning curve’

According to the London-based thinktank ODI, mechanisms developed under China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) could help deploy affordable low-carbon technologies in Africa, in much the same way that it facilitated “spillovers” of domestic infrastructure capacity, such as railways and ports, to the continent.

However, many SOEs accustomed to developing coal and hydropower face significant challenges to their ability to pivot towards renewables, Chiyemura tells Carbon Brief.

SOEs previously developed energy infrastructure through engineering, procurement and construction (EPC) contracts financed by policy bank loans, which only obligated them to build infrastructure, rather than operate and maintain it.

Now, African policymakers are increasingly pushing for equity financing models, encouraging Chinese companies to invest and hold shares in renewable energy projects.

However, Chiyemura says, this involves business processes that SOEs are not as used to.

For example, Ethiopia is developing a wind power plant through equity financing, which reduced debt pressures on the country. Chiyemura says this means Chinese companies will have to participate in open tendering systems, rather than the closed door negotiations to which they are accustomed:

“I remember one [company representative] saying: ‘Why do I have to waste my money and my time for a project that is [worth] maybe $80-90m?’…Companies see no value in spending time in [compiling] tender documents…But it shows their inexperience of understanding the regulatory requirements, which are fast changing in African markets.”

Furthermore, some companies also hold concerns about investment risks in Africa, Fu says.

The majority of African nations received low rankings from the World Bank “on their ease of doing business”, which means the regulatory environment is less conducive to the starting and operating of a local firm.

Fu adds that private Chinese companies prefer to partner with SOEs, which could link their involvement more firmly to the interests of the Chinese state, to limit their exposure to risks.

This is echoed in a paper co-authored by Chiyemura, which states: “The recent trend is to establish a consortium among these private and state companies…It is clear that new alliances or interest groups are taking shape within the existing policy community that are more dedicated to promoting wind and solar energy activities.”

Part of this, Chiyemura says, is due to the “fast-moving” environment of African energy regulations.

According to Dianah Ngui Muchai, a collaborative research manager at the African Economic Research Consortium, “flexible and innovative [financial] instruments” for renewables projects and “clear and realistic” policy goals are key to boosting investment in Africa.

South Africa and Ethiopia have been attempting to do this through their development of equity-financed wind power projects, Chiyemura tells Carbon Brief.

“It’s a learning curve, but we believe that maybe in the next five to 10 years…we are likely to see a number of Chinese companies developing these projects through equity financing”, he says.

FOCAC underscores shift to investment

These themes were echoed in the outcomes of this year’s FOCAC. In a keynote address, Chinese president Xi Jinping pledged financing worth 360bn yuan ($51bn) to Africa. Of this, 210bn yuan ($30bn) would be paid through credit lines and 70bn yuan ($10bn) through investments.

Part of this money will be used to fund a range of “clean energy” initiatives, with “green development” featuring heavily in official communications following the event. In his keynote speech, Xi stated that China will help develop 30 specific clean energy projects.

The declaration released after the meeting’s conclusion states: “China will support African countries in better utilising solar, hydro, wind and other sources of renewable energy and will further expand investment in Africa in energy-efficient technologies, new and high-tech industries, green and low-carbon industries and other low-emission projects.”

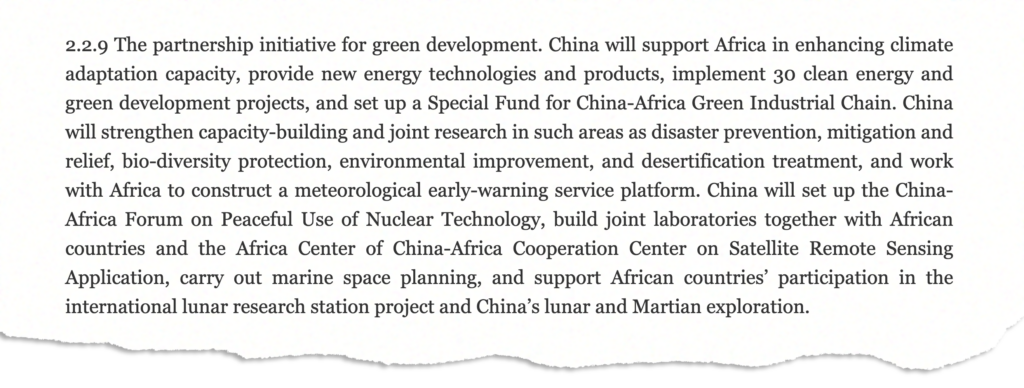

Furthermore, an action plan covering China-Africa cooperation between 2025 and 2027, released alongside the declaration, names ten overarching “partnership initiatives” guiding cooperation in the next three years – including in “trade prosperity”, “industrial chain cooperation” and “green” development, shown in the excerpt below.

As part of a larger cooperation effort on energy, China “will encourage investments in a range of renewable energy projects across Africa, including solar, wind, green hydrogen, hydroelectric [and] geothermal power initiatives”, it adds.

Xi also told FOCAC delegates that China will “encourage two-way investment[,]…enable Africa to retain added value, and create at least 1m jobs”.

In a press conference, South African president Cyril Ramaphosa said he was “very positively disposed to the amount of money Xi announced today” adding “it will be a great boon to the African continent”.

Analysis by the China-Global South Project is less optimistic, stating that the headline number is “highly misleading”.

The $30bn in credit lines “most likely…will be directed to benefit Chinese firms more than African stakeholders”, it adds, while the $10bn investment figure “shouldn’t count as part of a government financial pledge…since [it will] be made by Chinese private enterprises, particularly in the mining sector”.

Eric Olander, co-founder of the China-Global South Project, told Bloomberg that the credit may be used to “finance purchases of vast quantities of solar panels, batteries and electric vehicles” from China, for use in Africa.

But Dr Isaac Ankrah, senior research fellow at the Africa-China Centre for Policy and Advisory, tells Carbon Brief that Xi’s focus on developing “green growth engines” across the continent emphasises “a shift towards a more structured financing model for climate-resilient projects, focusing on technology transfer, capacity-building, and sustainable infrastructure”.

He adds that “these commitments could lead to a realignment of funding flows, making them more responsive to Africa’s specific energy transition needs”.

Whether the focus on investment at FOCAC leads to a tangible shift away from loan-driven projects remains to be seen, but ensuring that it happens is a priority for some African policymakers.

As Angola’s finance minister Vera Daves De Sousa said in an interview with Reuters: “We need to think outside the box, because the plain vanilla solutions of ‘you give me money, I’ll give you collateral’ is done.”

Sharelines from this story