Amid all the noise around the COP29 climate talks in Baku, Azerbaijan, it can be easy to lose sight of the negotiations and the core legal process at the summit.

This process often fades into the background, hidden from sight in closed-door negotiating rooms and late-night sessions, where diplomats – and then ministers – hash out their disagreements.

However, COP29 will culminate in a set of legal decisions, under the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and its associated Kyoto Protocol and Paris Agreement.

This set of legal texts lies at the heart of COP29 – and every other UN climate summit.

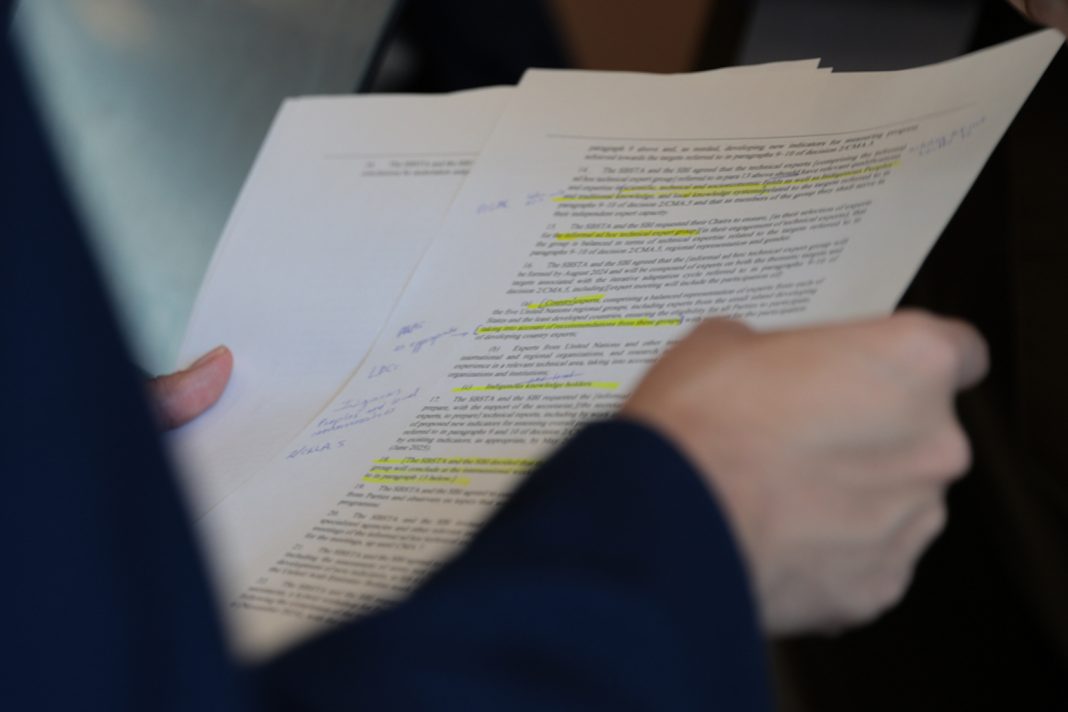

Negotiations over these documents are often fraught – and always closely fought. They can even be tripped up by a single misplaced word. A “shall” in place of a “should” – denoting a binding versus a non-binding requirement – nearly derailed the Paris Agreement in 2015.

Carbon Brief always takes a close interest in this process, attempting to scrutinise the hundreds of pages of draft negotiating text, as they evolve over the course of each two-week summit.

In order to keep track of these negotiating texts at COP29, Carbon Brief has created the interactive table below, which will be constantly updated, in close-to-real time.

Reading from left to right, the first column shows the topic of each document, for example, the “new collective quantified goal” on climate finance or Article 6 carbon markets.

Readers can search for keywords using the text box or reorder the entries by date or other columns. Carbon Brief will add notes to highlight key elements in each draft.

Typically, a draft negotiating text might begin its journey as a loose series of bullet points, written by a pair of negotiators appointed to lead a particular part of the talks.

These documents might be described as an “elements text” or – in the case of the first draft of the COP28 text on the global stocktake – as “building blocks”.

Later, text is turned into formal legal language. At this point, areas of disagreement are denoted with [square brackets], meaning the bracketed text has not yet been agreed by all parties.

Alternatively, the negotiating text might set out a series of “options” or “alt” text, with parties able to choose between a number of different passages that offer alternative formulations of words.

For example, the NCQG climate-finance negotiations have already reached the stage of a “substantive framework for a draft negotiating text”, published ahead of COP29.

This is written in legal language and currently includes 173 square brackets, as well as six “options”, across just nine pages of text. However, it does not yet have the formal status of a “draft text”.

Importantly, the lexicon of UN legal drafting is carefully calibrated and includes a “crescendo” of words, depending on how strong the drafters would like it to be.

In Glasgow at COP26, for example, there was a period of confusion over whether the word “request” was a stronger instruction than “urge” (it is).

Where agreement proves difficult to find, parties or the negotiators leading each process may propose “bridging text”. This is an attempt to find a way through apparently incompatible preferences on the way towards a final “landing zone” that will be acceptable to all parties.

Although it is not a foolproof measure, texts with many square brackets or options tend to be an indicator of a high level of disagreement between parties. For this reason, the table above is colour-coded according to the number of outstanding brackets under each agenda item.

On the other hand, some of the most difficult-to-resolve issues may revolve around a single word or passage of text.

Disagreements over one topic may get caught up in the “four-dimensional spaghetti” of countries’ competing priorities, with these potentially being used as bargaining chips or tradeoffs as part of a wider “package” of agreement over multiple issues.

At this point, it is common for parties to complain that an individual text – or an overall package – lacks “balance”, meaning their priorities get insufficient attention relative to the priorities of others.

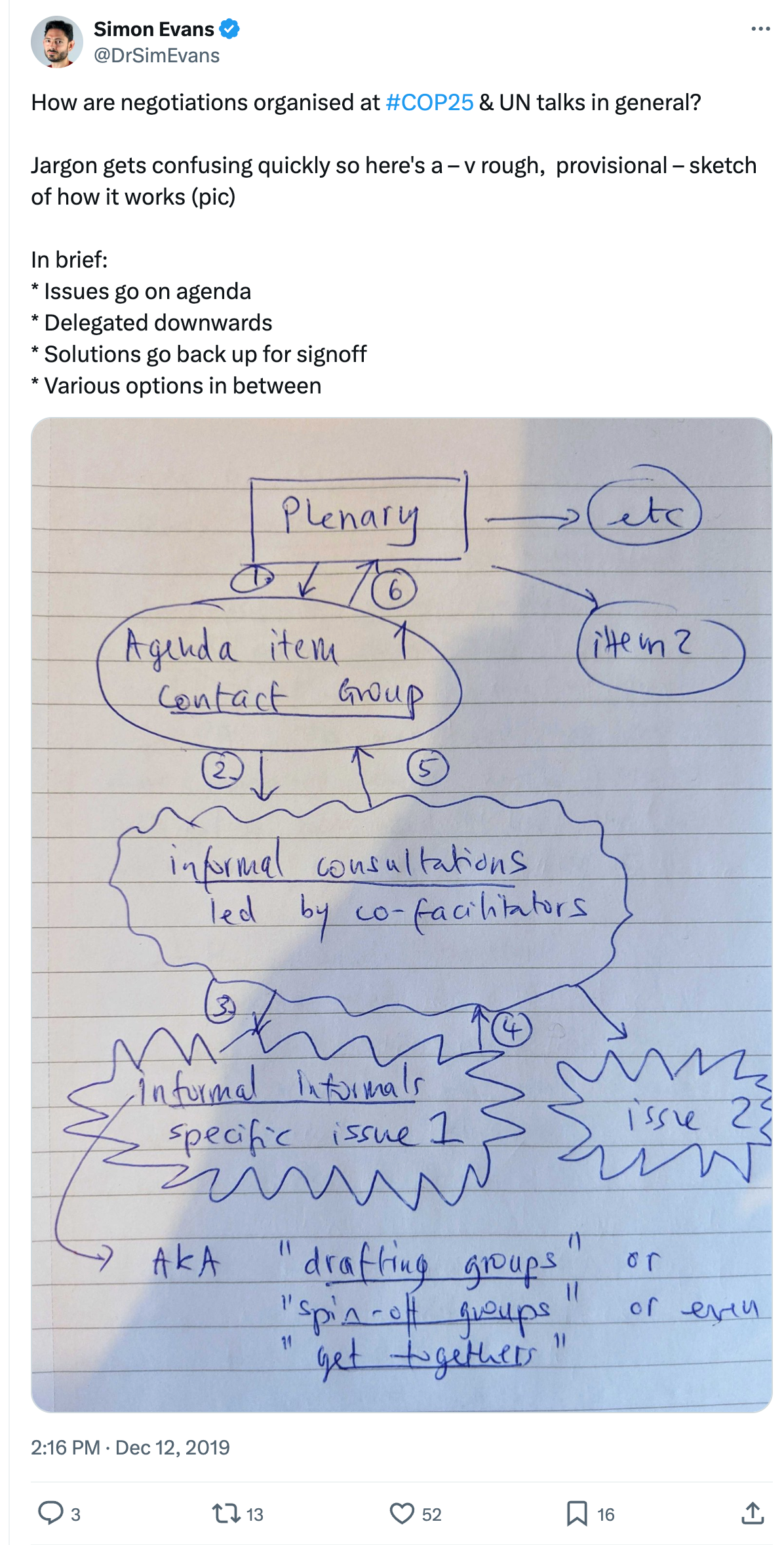

As draft texts progress through the course of the summit, they are discussed in “contact groups” for each topic, which may devolve into “informal” negotiations, “informal informals”, “drafting groups” or – towards the business end of the summit – small “huddles” of key players in any disagreement.

As parties narrow down the options and brackets, towards the end of each summit, they start to generate “clean” texts, which contain no areas of disagreement and can be converted into “draft decisions”, that are ready for formal adoption at the closing plenary of the meeting.

Finally, at the closing plenary, each draft decision must be gavelled through by the COP president, signifying its formal adoption as a legal agreement and outcome of the summit.

Words by Simon Evans. Tracker built by Verner Viisainen.

Sharelines from this story