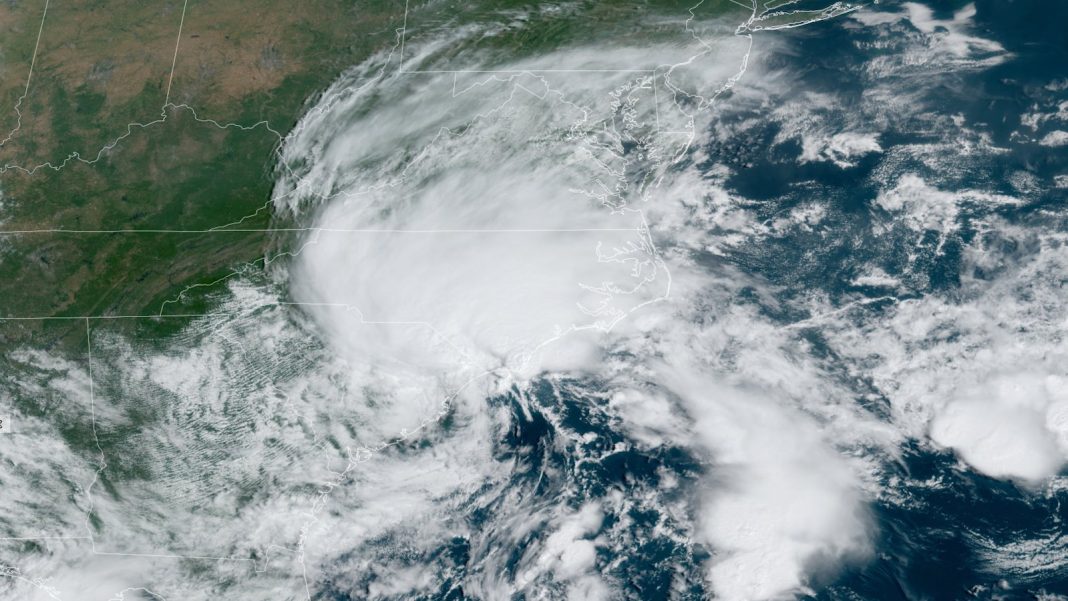

Even as Potential Tropical Cyclone 8 struggled to earn itself a name off the Southeast U.S. coast on Monday, it was bringing tropical-storm-like weather to the coast of North Carolina. Satellite imagery and reconnaissance flights showed that PTC 8 was entangled in a persistent front that was stretching out the circulation and keeping it from becoming a distinct, symmetric low.

As of 11 a.m. EDT, the elongated, poorly defined center of PTC 8 was located nearly 100 miles east of Charleston, South Carolina, moving north-northwest at 5 mph. Virtually all of PTC 8’s stronger showers and thunderstorm activity (convection) were concentrated well north of the center across and near the coast of eastern North Carolina and in a separate area well offshore. Top sustained winds were 50 mph, more than strong enough to make PTC 8 a tropical or subtropical storm. But because PTC 8 was structured more like a frontal or coastal storm than a non-frontal cyclone, the National Hurricane Center had not yet named it. Odds were rising that PTC 8 would make landfall in South Carolina on Monday night without ever becoming Tropical or Subtropical Storm Helene.

Regardless of PTC 8’s status, Carolinians were feeling its presence on Monday, especially on the system’s north side, toward the southern coast of North Carolina from Wilmington to Cape Fear. A small-scale low-pressure center and intense band of thunderstorms was sweeping inland near Wilmington at midday, with wind gusts of 45 mph reported there at 8:52 a.m. EDT.

As PTC 8 slogs ashore and weakens, the heaviest rains and strongest winds will move across this area into early Tuesday, perhaps totaling six to eight inches in a few areas. Localized amounts could be even higher, as reflected by a cluster of totals well over 10 inches recorded by weather stations on Bald Head Island, which juts into the Atlantic just south of Wilmington.

As of noon EDT Monday, the Bald Head Island Club mesonet station of the North Carolina Climate Service had picked up 15.03 inches in the preceding 24 hours. Further inland, top two-day rainfall totals from the CoCoRaHS volunteer observing network through Monday morning included 3.61 inches near Morehead City, North Carolina, and 3.5 inches just northeast of Wilmington. The torrential rains combined with storm surge (see below) have led to inundations exceeding three feet in Carolina Beach, North Carolina.

Widespread inland flooding is not expected from PTC 8, as streamflows have been running near normal across eastern North Carolina, but some flash flooding is possible where localized downpours occur.

Storm surge from PTC 8 was pushing across the coast on Sunday and Monday. At high tide Sunday afternoon, moderate flooding was reported at Charleston Harbor, and minor flooding was occurring or projected for Monday afternoon and evening along the coast from Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, to Beaufort, North Carolina. Peak storm surge could produce inundations of one to three feet across a Storm Surge Warning area that extended from South Santee River, South Carolina, to Oregon Inlet, North Carolina, including well inland along the Pamlico, Pungo, Neuse, and Bay rivers of southeastern North Carolina.

Minor to potentially moderate coastal flooding will remain possible well north along the mid-Atlantic coast over the next several days, as PTC 8 moves inland and continued onshore flow combines with astronomical high tides.

Underwhelming Gordon hangs on as a tropical depression; little else in the Atlantic this week?

Tropical Depression Gordon, downgraded from minimal tropical-storm status on Sunday, is hanging on by its fingernails in the remote eastern tropical Atlantic. At 11 a.m. EDT Monday, a ragged zone of convection remains focused east of Gordon’s low-level center, which has been partially exposed at times. Top sustained winds were 35 mph, and Gordon was nearly 1,000 miles east of the Leeward Islands, moving west at 7 mph. An approaching upper-level trough will begin hauling Gordon northward by midweek, and it could regain tropical-storm strength, but Gordon poses no risk to land areas.

No new systems of concern appear likely to take shape in the Atlantic over the next seven days, according to the National Hurricane Center’s Tropical Weather Outlook issued at 2 p.m. Monday. On average over the past several decades (1991-2020), the seventh, eighth, and ninth named storms have all developed by September 22, so making it to next Sunday without the eighth storm (assuming PTC 8 doesn’t become Helene) would keep the Atlantic well behind the usual climatological pace. As of Sunday, September 15, real-time statistics from Colorado State University showed that the 2024 season was also behind the 1991-2020 pace on hurricane days (13.25 versus the average of 15.2) and accumulated cyclone energy (61 versus the average of 71.9). This week’s activity will not be enough to keep the 2024 season from falling even further behind in those metrics – a welcome development for coastal residents, to be sure, but also a remarkable and puzzling one given multiple forecasts for a hyperactive 2024 Atlantic season.

Beyond this week, the GFS and European ensemble models are converging on the possibility of a system developing in the western Caribbean and moving northward into the Gulf of Mexico later next week. It’s far too soon to be confident about any details, though.

Jeff Masters contributed to this post.

We help millions of people understand climate change and what to do about it. Help us reach even more people like you.