On 9 September, the long-awaited report from former Italian prime minister Mario Draghi into EU competitiveness was published.

The future of European competitiveness report has a strong focus on climate and energy, laying out a joint decarbonisation and competitiveness plan, along with plans for boosting security and reducing dependencies, closing the innovation gap and more.

These plans look to tackle the “existential threat” facing the bloc. As Draghi notes in the foreword:

“Europe’s fundamental values are prosperity, equity, freedom, peace and democracy in a sustainable environment. The EU exists to ensure that Europeans can always benefit from these fundamental rights. If Europe can no longer provide them to its people – or has to trade off one against the other – it will have lost its reason for being.”

The report suggests that Europe needs to invest €750-800bn a year to keep pace with competitors, such as China and the US.

In particular, investment should be used to boost clean energy generation and transmission, while changes to the energy markets can help bring down energy bills for households and businesses. This in itself will help boost the competitiveness of industry in the bloc, it notes.

The findings of the 400-page report will feed into the development of the European Commission’s new plan for “Europe’s sustainable prosperity and competitiveness”. This includes the clean industrial deal, which will be presented in the first 100 days of the commission’s mandate.

In this Q&A, Carbon Brief takes a look at why the report was produced, what challenges were identified and what suggestions it makes.

Why has Draghi produced this report?

Draghi, a former Italian prime minister widely credited with “saving the euro” during his time as European Central Bank president, was asked by European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen to write this report a year ago.

In her plans for the current European Commission between 2024 and 2029, Von der Leyen said she would draw on Draghi’s work to design “a new plan for Europe’s sustainable prosperity and competitiveness”.

The report was initially expected to come out before the EU elections, which ultimately saw Von der Leyen win her second term as president. However, after weeks of rumours, officials confirmed that it would be delayed until September.

Competitiveness has been a big topic in the EU in recent months. Both Belgium and Hungary deemed it a priority during their presidencies of the Council of the EU this year.

Geopolitical changes, including competition from the US and China, are often cited as the key drivers of these concerns. Draghi summarises the current state of play in the foreword to his report:

“The previous global paradigm is fading. The era of rapid world trade growth looks to have passed, with EU companies facing both greater competition from abroad and lower access to overseas markets. Europe has abruptly lost its most important supplier of energy, Russia. All the while, geopolitical stability is waning, and our dependencies have turned out to be vulnerabilities.”

Another former Italian prime minister, Enrico Letta, was also enlisted to produce a separate report – released in April – evaluating the EU’s single market. That, too, focused on the bloc’s competitiveness, concluding that:

“The lack of integration in the financial, energy and electronic communications sectors is a primary reason for Europe’s declining competitiveness.”

Von der Leyen herself has made it clear that she sees the EU’s “green” transition as a core part of improving the bloc’s competitiveness. This includes working on industrial policy that will allow EU nations to boost their share of the global clean technology market.

What are the areas of ‘transformation’ identified in the report?

The Draghi report concludes that the EU “faces three major transformations”.

The first is the need to accelerate innovation. This section of the report focuses primarily on the EU’s poor performance in the digital sector, especially compared to the US, as the world stands “on the cusp of another digital revolution” driven by artificial intelligence.

The second “transformation” is the general need to reduce energy prices across the EU. This has significant implications for the bloc’s energy and climate policies.

Despite prices falling from their peak following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the report notes that electricity and gas prices facing EU companies are still very high.

The charts below show how the cost of both power (left) and gas (right) for EU companies – indicated by the blue lines – are far higher than in China and the US, indicated by the yellow and grey lines, respectively.

It identifies three overarching reasons for this. First, making the comparison with the US, the report says Europe has a relative lack of natural resources. (For example, the US is the largest oil producer in the world, whereas the EU imports 98% of its oil and 90% of its gas.)

Second, it says the EU has failed to make better use of its collective bargaining power – despite being the world’s largest importer of gas and liquified natural gas (LNG). Crucially, the final point the report identifies is an array of “fundamental issues with the EU’s energy market”.

More specific issues identified in the report include the following:

- Decoupling electricity prices: Market rules in the power sector across Europe do not fully decouple the price of renewable and nuclear power from higher and more volatile fossil fuel prices. The report says this “may prevent” the full benefits of decarbonising electricity generation from reaching households and companies.

- Gas derivative markets: The report says that the concentration of “a few non-financial corporates” undertaking “most trading activity in European gas markets” had contributed to the volatility of gas prices.

- Permitting: A “lengthy and uncertain permitting process” for new electricity generation projects and grids has proved to be a “major obstacle”, according to the report. It notes that building solar and onshore wind farms can take several years in some member states, and notes that “the time devoted to analyses of environmental impacts” is a big contributor to longer lead-in times.

- Energy taxation: While the report notes that taxation can work as a “policy tool to encourage decarbonisation”, in Europe it is often an important source of revenues for member states and contributes to higher retail prices. By contrast, the report points out that the US “does not levy any federal taxes on electricity or natural gas consumption”.

The report emphasises the need to ensure that its policies are “in sync with the EU’s decarbonisation objectives” – noting, for example, that industries with high energy use will require more investment to meet net-zero goals.

Over the “medium term”, it notes that cutting emissions will help to reduce costs by switching power generation to cheap, clean energy sources. However, the report adds:

“Fossil fuels will continue to play a central role in energy pricing at least for the remainder of this decade. Without a plan to transfer the benefits of decarbonisation to end-users, energy prices will continue to weigh on growth.”

Many clean technologies, such as wind turbines and electrolysers, are already made in great numbers across Europe. The report emphasises the need for the EU to continue strengthening this sector and makes the link between it and the wider issues of climate targets and energy prices:

“Decarbonisation offers an opportunity for Europe to lower energy prices and take the lead in clean technologies…while also becoming more energy secure.”

The final area of “transformation” identified by Draghi concerns the EU’s reaction to “a world of less stable geopolitics”.

Here, too, there are links to energy and climate policies, especially as other major economies become increasingly protectionist in their economic policies. The report says that the EU currently relies on China for critical minerals, while China relies on the EU to buy its products – but now other nations “are actively seeking to reduce their dependency”.

Access to critical minerals is essential to build clean energy technologies, but their supplies are highly concentrated in a handful of nations – including China. The report explains that these materials are currently “subject to a global race to secure supply chains, and Europe is currently falling behind”.

What does the report suggest to boost competitiveness?

One of the most significant recommendations in Draghi’s report is a substantial increase in investment.

The report suggests EU investment needs to rise by around five percentage points of GDP to levels last seen in the 1960s and 1970s. It points to the US Marshall Plan as a point of comparison, which included an investment 1-2% of GDP annually between 1948 and 1951, highlighting the scale of the investment the EU needs.

Joint borrowing should be used to fund the bloc’s green transition, building on the Next Generation funds model, which financed investment projects across six key areas designed to boost the green transition.

This increased investment can help bolster industry and lower electricity prices for households and businesses. The report notes:

“The decarbonisation of the energy system is an opportunity for the EU in reducing its dependence on fossil fuels to ensure its competitiveness, the affordability and security of supply.”

It will take time to reap the full benefits of decarbonisation, the report says. In the meantime, the EU must be prepared to deal with an energy system that may be less flexible, require “massive investment” to avoid bottlenecks and may experience higher and volatile prices.

But, ultimately, the decarbonisation of the energy system can boost European competitiveness by “radically decreas[ing] import dependency”. For instance, the 2040 Climate Target Plan suggests the EU will import between 190bn cubic metres (bcm) and 240bcm of gas by 2030, compared to 334bcm in 2021.

The decarbonisation of energy could foster massive deployment of clean energy sources with low marginal generation costs, such as renewables and nuclear.

To support this, the permitting and administrative processes should be simplified and streamlined to accelerate the roll out of renewables, grid upgrades and flexibility infrastructures such as batteries and other forms of storage, the report suggests.

This includes addressing a lack of resources within the administrative sectors that support renewables, and a greater focus on digitalising national permitting processes, amongst other suggestions.

Some European member states have experienced a double-digit increase in the volume of permits issued for onshore wind since Article 122 Emergency Regulation was brought into force – this formed part of the EU’s response to the energy crisis, and included provisions to ease the deployment of renewables.

The report recommends extending these acceleration measures and emergency regulations beyond renewables and generation assets to heat networks, heat generation, hydrogen and carbon capture and storage infrastructure.

It also suggests the creation of a permanent European coordinator, to assist in obtaining the necessary permits for renewable and supporting green energy technologies.

However, renewables will not be able to bring the expected benefits if the grid continues to become a bottleneck, the report warns. For every euro spent on clean power in Europe over the 2022-40 period, 90 cents of grid investment will be required to achieve the EU’s climate ambitions.

Draghi suggests that energy infrastructure planning should shift to a European level, and calls for the creation of a new EU-level planning coordinator, which could speed-up the building of cross-border power links.

This could help manage bottlenecks that are emerging, such as increased grid costs, as increasing infrastructure investment requirements are expected to increase over the next decade. For example, TenneT – the Transmission System Operator for the Netherlands and a significant part of Germany – expects German grid fees to increase by 185% by 2045, the report says.

The document points to the International Energy Agency’s (IEA’s) grid delay scenario, which estimates that insufficient grid deployment globally could slow the rollout of renewables, increase emissions and result in twice as much coal and gas use in 2050.

Therefore, the report says, substantial investment in distribution and transmission grids is needed, estimated at over €500bn across this decade by the European Commission.

Addressing system needs could reduce energy costs by €9bn a year in 2040, the report notes, more than offsetting the €6bn a year investment needed.

While the bulk of the grid investments needed will be within countries, interconnections between countries will also play a “fundamental role”, the report notes. As such, the next Multiannual Financial Framework – the seven-year framework regulating its EU annual budget – should “reinforce the EU instrument dedicated to financing interconnectors”, it says.

What changes to markets are needed?

Beyond investment into grids and clean energy technologies, the report proposes reforming Europe’s energy market to ensure more of the benefits of clean energy are passed onto consumers.

The report calls for the impact of volatile gas prices to be reduced through reinforcing joint procurement to make use of Europe’s market power and establish long-term partnerships with reliable and diversified trade partners.

This follows the price of gas skyrocketing following the Russian invasion of Ukraine and subsequent disruptions in supply. The EU has now reduced its imports from Russia from over 40% in 2021 to about 8% in 2023, and is continuing to eye further diversification.

The report suggests the EU should also encourage a shift away from spot-linked sourcing in the gas market – where gas is bought and sold for immediate, or near-immediate delivery – to reduce volatility by limiting speculative behaviour.

Additionally, transferring the benefits of decarbonisation requires greater decoupling of the price of gas from clean energy, the report states. The EU should build on tools introduced under the new Electricity Market Design, such as power purchase agreements (PPAs) and two-way contracts for difference (CfDs) subsidies, it continues.

Expanding the use of PPAs and CfDs would help to pass on the benefits of cheap renewables more directly, minimising the impact of gas prices on electricity bills.

The report supports Europe’s internal energy market and its marginal pricing structure, whereby everyone receives the same price for electricity in a wholesale market, in its current form. It confirms that this system has reduced price variables across countries in the union, delivering €34bn in cost savings for households and businesses.

In a statement, European electricity sector association Eurelectric’s secretary general Kristian Ruby said:

“Draghi’s report highlights the importance of long-term instruments such as PPAs and CfDs to help better transfer the benefits of cheap renewable and clean energy to consumers and to make our energy prices more competitive. To see PPAs volumes rise to the necessary levels, however, all EU member states must urgently implement the agreed electricity market reform.”

The report particularly focuses on the impact energy markets could have on developing industry, noting that Europe must “confront some fundamental choices about how to pursue its decarbonisation path while preserving the competitive position of its industry”.

This includes suggesting the development of market platforms to contract resources and pool demand between generators and buyers to increase the uptake of PPAs in the industrial sector.

Beyond these elements, other suggestions for market changes within the Draghi report include that the European Investment Bank and national promotional banks could provide counter guaranties and specific financial products for small consumers or suppliers that lack a proper credit rating.

Additionally, a “genuine Energy Union” should ensure that central market functions of relevance for an integrated market are “performed centrally and subject to proper regulatory oversight”, the report says.

What should be done to develop international competitiveness?

Trade policy will be “fundamental” to combine decarbonisation with competitiveness, Draghi’s report suggests. Supply chains will need to be secured, new markets grown and state-sponsored competition offset, it states.

Europe must confront some key choices about how to pursue decarbonisation while preserving the competitive position of its industry, the report continues.

In particular, the report identifies China and the US as major competitors for the EU, where competition is becoming acute in industries such as clean tech and electric vehicles (EVs).

Writing in the Economist following the report’s publication, Draghi explains:

“Europe faces a possible trade-off. Increasing reliance on China may offer the cheapest route to meeting the EU’s climate targets. But China’s state-sponsored competition represents a threat to otherwise productive industries.”

This marks a continued shift in how the EU comments on China, with climate commissioner Wopke Hoekstra stating in a speech last week that “Europe has a China problem”. He went on to discuss the need to rebalance competition, calling for equal rules for both the EU and China.

Amongst the challenges that need to be rebalanced to secure international competitiveness for the EU is the impact of subsidies on key industries such as renewables and EVs.

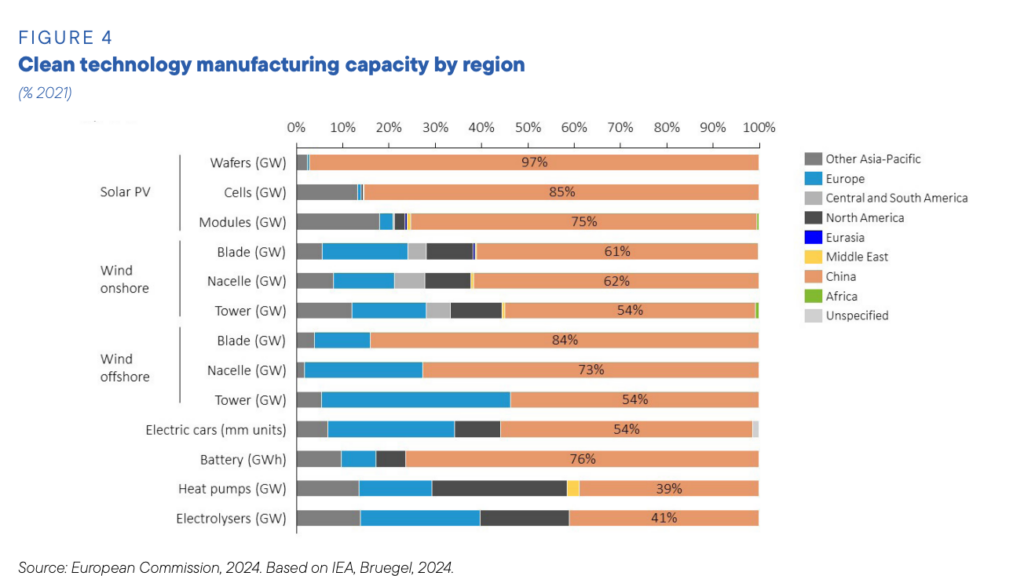

The report draws attention to high levels of subsidies in parts of the world that have contributed to overcapacity for certain sectors – a challenge for EU industry as it is expected to increase in the future. As seen in the chart below, taken from the report, China (orange) dominates in manufacturing of renewable technologies, heat pumps, batteries and EVs when compared to Europe (light blue), North America (black) and other Asia-Pacific countries (dark grey).

Funding for the green transition in the EU is often more complex to access than in other regions, again creating challenges for competitiveness, the report notes.

Draghi argues Europe should deploy “a mixed strategy that combines different policy tools and approaches for different industries” to ensure global competitiveness.

In particular, the report notes that “The problem is not that Europe lacks ideas or ambition…but that innovation is blocked at the next stage: we are failing to translate innovation into commercialisation.” As such the report focuses on boosting production in the EU.

This should include tackling high energy prices for energy intensive industries by ensuring access to a competitive supply of gas in the short term, and sufficient and decarbonised electricity more broadly.

Draghi’s report argues that more funds from the bloc’s emissions trading scheme (ETS) should be channelled towards heavy industry. While the report notes that the EU’s ETS can be “high and volatile”, it does not propose changing it.

Other key regulatory mechanisms include the carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM), which can help mitigate trade risks by protecting businesses from carbon-related tariffs and penalties. It must be implemented consistently, and its design closely monitored and improved, the report states.

Further investment should be directed into decarbonising industries and developing emissions-abatement technologies such as carbon capture and storage (CCS). The report notes that funding for energy intensive industries is currently “insufficient”, with too little of the EU’s Innovation Fund along with other schemes supporting these sectors.

Beyond these, the report includes specific recommendations for clean technology sectors, including calls for the development of an industrial action plan for the automotive sector. It highlights the countervailing tariffs recently adopted by the European Commission against Chinese automotive companies making EVs. This is designed to “level the playing field”, it states.

However, it notes that taking a US approach of “systematically shutting out Chinese technology” would set back the energy transition and impose higher costs on the EU economy.

It notes that if the Chinese EV industry were to follow a similar trajectory of subsidies as have been applied in the solar PV industry, EU production of EVs would decline by 70%. This would hit EU producer’s global market share by 30 percentage points, as well as having a significant impact on the almost 14 million Europeans employed directly or indirectly in the sector.

The report comes after recent news that Volkswagen is considering closing its German EV plant to save “billions in costs”, as European carmakers’ continue to report problems in switching from petrol and diesel vehicles to electric models.

Sharelines from this story