The 119th Congress comes with a price tag.

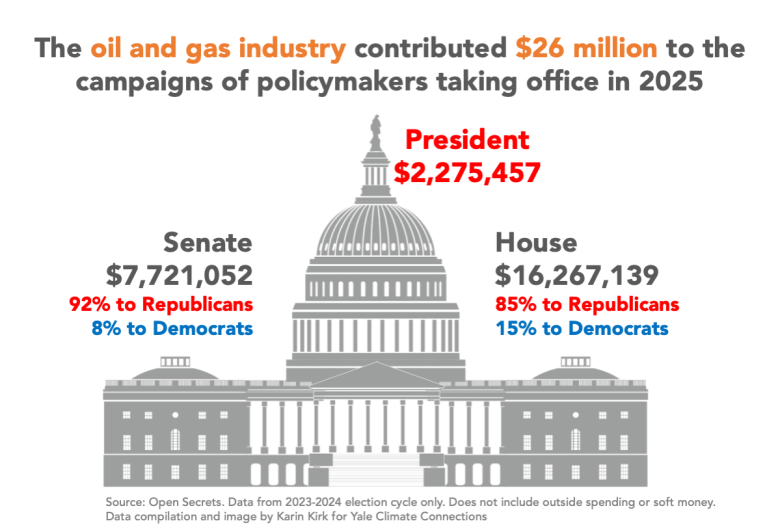

The oil and gas industry gave about $24 million in campaign contributions to the members of the U.S. House and Senate expected to be sworn in January 3, 2025, according to a Yale Climate Connections review of campaign donations. The industry gave an additional $2 million to President-elect Donald Trump’s campaign, bringing the total spending on the winning candidates to over $26 million, 88% of which went to Republicans.

The fossil fuel industry exerts substantial financial power within the U.S. political system, and these contributions are only the tip of the (melting) iceberg.

Outside spending: An order of magnitude more than candidate contributions

The 2024 presidential election saw over $4 billion in various contributions to the candidates’ campaign committees and outside groups supporting them. Most of the money in politics isn’t given to specific candidates. Rather, it goes to political action committees, known as PACs, and political party committees. This is called outside spending.

In the 2024 election cycle, the oil and gas industry funneled over $151 million to into the election via this additional spending, according to Open Secrets. The industry gave $67 million to candidates (including those who didn’t win), bringing the total to a staggering $219,079,058 spent by the oil and gas industry to influence the 2024 election. The vast majority of this money went to Republicans, including nearly $23 million of oil and gas money donated to Donald Trump’s campaign and PACs supporting him.

These figures only include reported contributions – from individuals, political action committees, and various organizations. Transactions reported to the Federal Election Commission are gathered into a user-friendly format by Open Secrets, a nonpartisan, independent research group that tracks political donations. This data is easy to explore on the Open Secrets oil and gas summary page.

In 1907, the U.S. banned corporate money from politics

The history of corporate money in American politics follows a convoluted timeline. In 1907, President Theodore Roosevelt signed a law banning political contributions from corporations, a measure that was widely popular at that time – and perhaps would be again today. In 1935, public utility companies were prohibited from making political contributions, clamping down corporate influence in elections even further. But over time, these policies were softened and ultimately reversed, culminating in the 2010 Citizens United ruling by the Supreme Court that opened the floodgates to unlimited spending by corporations seeking to assert political influence.

Today, money enters the political system from individuals, corporations, and special interest groups

Money from the fossil fuel industry flows into the political system in a few different ways.

Individuals can give money directly to candidates’ campaigns, and the size of these direct donations is capped at $3,300 per candidate. But individuals can also give money to political action committees, state party committees, and national party committees. The sum of these different categories allows wealthy individuals to give over $180,000 per election, in addition to funding specific candidates at $3,300 each.

Corporations technically can’t give money directly to federal candidates, but there are several avenues that companies can use to influence elections, such as super PACs or trade associations. This outside money is used for organizing, conducting campaign activities, and influencing elections.

The Citizens United ruling allows certain types of political action committees – particularly super PACs – to solicit and accept unlimited contributions from individuals, corporations, special interest groups, and labor organizations. (See a summary chart of contribution limits from the FEC.)

After Citizens United, outside spending from the fossil fuel industry was pumped into politics like never before, rising from $2 million to over $150 million over the course of just four presidential election cycles.

Lastly, there’s “dark money,” for which disclosure of the money’s source is not required. Dark money allows wealthy donors and corporations to infuse money into political activities without these activities being traced to them. Dark money can also be used for issue campaigns that may not be directly related to an election but help the fossil fuel industry’s public image, such as advertisements suggesting that the pollution and damages caused by burning fossil fuels are not serious. In some cases, the amount of money is counted in the outside spending tallies above, but the source of the funds is anonymous. Dark money from the fossil fuel industry is playing a growing role in funding misinformation and influencing lawmakers.

Fossil fuel money in politics overwhelmingly flows to Republicans

In the quaint olden days of 1992, fossil fuel election spending was somewhat more evenhanded than it is today, with around 34% going to Democrats and 66% to Republicans. Today, Democrats still receive around the same amount of money from the oil and gas industry as they did in 1992. Republicans, on the other hand, have seen a fourfold increase in fossil fuel contributions to their campaigns. In the 2024 election, 88% of oil and gas money went to GOP lawmakers.

What do fossil fuel donors get for their money?

A 2019 study on the effect of oil and gas money in politics found that oil and gas companies tend to reward candidates who already had voted along with their industry’s best interests. In effect, industry money was used to invest in legislators with a proven record of siding with the oil and gas industry. (Note that several authors of the study are affiliated with the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication, the publisher of this site.)

The financial might of the fossil fuel industry doesn’t stop once the new Congress is sworn into office. The industry spends over $100 million each year to lobby politicians to enact legislation favorable to the industry, such as voting against climate policy, slowing the adoption of cleaner energy, adopting a lenient stance on pollution, and imposing strict punishments on peaceful protests.

At the same time, the industry further uses its power and influence to sow doubt in climate science, spread misinformation, and attempt to sway the courts. The fossil fuel industry has poured money into multiple avenues to protect its business model, even as the damages caused by burning oil, gas, and coal have become widespread.

Track your elected officials

The situation can feel overwhelming. But a good first step is to use this transparent data and bring these numbers to light. The Open Secrets website makes it easy to look up every U.S. senator and representative for elections going back to 1990. The data is sortable, downloadable, and intuitive to use.

This article focuses on the oil and gas industry specifically, and to dig deeper into other aspects of the fossil fuel industry, you can access data from coal mining, gas pipelines, and electric utilities. You can also search any federal politician within Open Secrets and learn about the industries, PACs, and individuals that have contributed money to their campaign.

You can look up any donor on Open Secrets, and in the spirit of transparency, the database includes the author of this article, who has made small donations to various candidates in the past few elections. The modest amount of money donated by regular citizens offers a stark contrast to the multiple millions of dollars the fossil fuel industry spends on electoral politics.

To learn about the campaign finances of state and local officials, use the Follow the Money database.

How does a politician’s voting record square with the wishes of constituents? You can also review environmental scorecards for each member of Congress produced by the League of Conservation Voters. Yale’s Climate Opinion Maps – created by the publisher of this site – contain public opinion data about climate change, energy, and climate policy from every congressional district in the U.S. By combining these data sources, it becomes easy to see where politicians may be working for industry’s interests rather than the public’s.

Resentment of large and powerful corporations is already widespread and bipartisan, and an uneasy awareness of corporate power may become a growing theme of 2025. But the first step is to take stock of the problem, and that information is right at our fingertips.

Only 28% of U.S. residents regularly hear about climate change in the media, but 77% want to know more. You can put more climate news in front of Americans in 2025. Will you chip in $25 or whatever you can?