A Hurricane Warning and a Storm Surge Warning are up for most of the coast of Louisiana as Tropical Storm Francine heads toward landfall. Francine is expected to intensify into a hurricane by Tuesday evening, then level off in strength or weaken before making landfall as a Category 1 storm in Louisiana on Wednesday afternoon or evening.

Francine is growing more organized

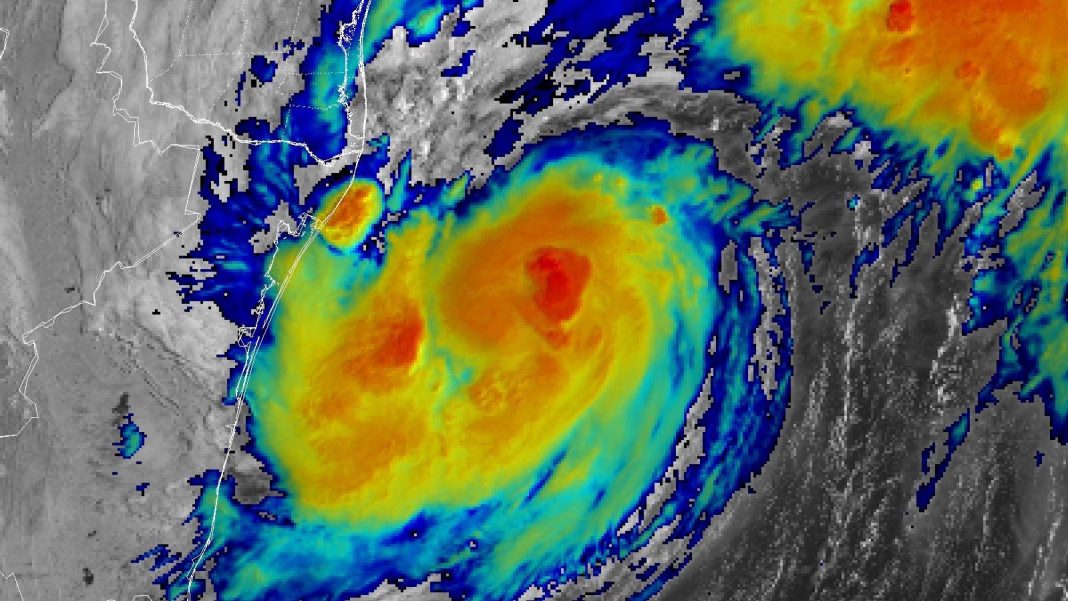

At 11 a.m. EDT Tuesday, Francine was located 425 miles (690 km) southwest of Morgan City, Louisiana, moving north-northeast at 8 mph (13 kph), with top sustained winds of 65 mph (100 kph) and a central pressure of 988 mb. Satellite imagery and Brownsville, Texas radar showed that Francine had a modest-sized area of heavy thunderstorms which were growing more organized. Heavy rains from the storm were affecting the coasts of northeastern Mexico and southern Texas.

Conditions were favorable for development, with record-warm ocean temperatures near 30.5 degrees Celsius (87°F), light wind shear of five to 10 knots, and a moist atmosphere. However, there is some dry air to the storm’s west over Texas and Mexico that interfered with development overnight.

Record-warm waters in the Gulf of Mexico

On Tuesday through Wednesday morning, Francine will benefit from record-warm ocean temperatures near 30-30.5 degrees Celsius (86-87°F). This is about 1 degree Celsius (1.8°F) above the 1981-2010 mean and is the warmest on record for this time of year. Human-caused climate change made this ocean warmth over 200 times more likely along portions of Francine’s track, according to the Climate Central Ocean Shift Index (Fig. 1). These warm waters are evaporating near-record amounts of water vapor into the air, which will increase Francine’s heavy rains (see Tweet below).

Francine is forecast to break atmospheric moisture records as it moves into Louisiana on Wednesday 💧

Likely stemming from record high oceanic heat content in the Gulf of Mexico and similar to Hurricane Debby in August, Francine is forecast to come with record-breaking… pic.twitter.com/ORWglPdElv

— Ben Noll (@BenNollWeather) September 10, 2024

Track forecast for Francine

There is some modest uncertainty in the track forecast, both cross-track (which part of the coast the storm will hit) and along-track (when it will hit). The forecast models have shifted more to the east in their latest runs, increasing the threat to New Orleans. Heavy rains in excess of four inches are expected along a large swath of the Gulf Coast, from western Louisiana to coastal Alabama.

Intensity forecast for Francine

Favorable conditions for Francine’s intensification will continue through early Wednesday morning. Rapid intensification (defined as a 35-mph increase in winds in 24 hours) is looking less probable than it was yesterday, though: The 12Z Tuesday run of the SHIPS model gave Francine just a 12% chance of rapidly intensifying by 35 mph in the 24 hours ending at 8 a.m. EDT Wednesday, which would bring it to Category 2 strength with 100 mph winds. The model gave a 10% chance Francine would become a major Cat 3 hurricane with 115 mph winds by Wednesday night.

Late Tuesday night through Wednesday, as Francine approaches the coast of Louisiana, wind shear is expected to rise to the high range, 20-30 knots, and dry air on the west side of the storm may be able to attack the core of the storm, causing weakening. There will also be less ocean heat energy available. These factors should cause Francine to stop intensifying six or more hours before landfall, and the top intensity models predict Francine will make landfall with sustained winds between 75-100 mph (120-160 kph) – a Category 1 or 2 hurricane. Ensemble models suggest that if Francine tracks more to the east (resulting in an increased threat to New Orleans), it may be a stronger storm (Fig. 2).

A damaging storm surge for Louisiana

A storm surge of 1-2 feet (0.6-1.2 m) was already being observed along much of the Texas coast on Tuesday morning, causing some minor coastal flooding, according to NOAA’s Tides & Currents website. A much larger storm surge of five to 10 feet (1.5-3 m) is expected along the Louisiana coast near and to the right of where the center makes landfall, causing major flooding. The coast of Louisiana is one of the most vulnerable locations in the world for high storm surges because of the large expanse of shallow water offshore. Francine’s angle of approach to the coast – from the south-southwest – makes it less of a storm surge threat for New Orleans than for a storm approaching from the south or the southeast.

High tide at Amerada Pass in central Louisiana is early Thursday morning at 3:30 a.m. EDT (7:30Z); low tide is Wednesday afternoon at 5:30 p.m. EDT (21:30Z). The difference in water level between high and low tide is about 1.5 feet (0.5 m), so the timing of Francine’s landfall will be a significant contributing factor in determining how much coastal flooding occurs. The 11 a.m. EDT Tuesday National Hurricane Center forecast called for a landfall near 6 p.m. EDT Wednesday, near the time of low tide. However, we should expect the timing of landfall could vary by up to four hours from this. The timing of landfall from the 06Z Tuesday runs of our six top hurricane models had a nine-hour range, from 2-11 p.m. EDT.

Louisiana hurricane history

Louisiana has been hit by so many destructive hurricanes in recent years that the landfall of Francine will cause less damage than might be expected, since there’s less left to destroy. Twelve hurricanes have made landfall in the state since 2000. The most destructive were the twin demon hurricanes of 2005, Katrina and Rita. Katrina’s $190 billion in damage (2024 USD) still ranks as the most destructive weather disaster in world history; Rita’s $28 billion in damage ranked as America’s fourth costliest hurricane at that time.

Five hurricanes have hit Louisiana during the past five years, including two Category 4 storms with 150 mph winds that were tied as the strongest on record to hit the state west of the Mississippi River, Laura of 2020 and Ida of 2021. (Hurricane Camille in August 1969 is the strongest hurricane of record to hit Louisiana; it was a Cat 5 when it passed over coastal Louisiana east and north of the Mouth of the Mississippi River en route to its final landfall in Mississippi.) Laura caused $23 billion in damage (2024 USD) in Louisiana, and Ida cost the state $66 billion. Hurricane Zeta (2020, $5.3 billion) and Hurricane Delta (2020, $3.5 billion) were also very damaging.

Bob Henson contributed to this post.

We help millions of people understand climate change and what to do about it. Help us reach even more people like you.